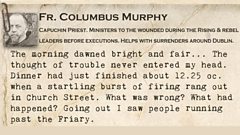

Father Columbus Murphy

Priest in the crossfire

Daniel Murphy was born on 17 June 1881 in Cork to James and Sarah Murphy (nee Flynn) of Ethelville, Western Road. He was baptised two days later in St Finbarr's Church.

We were never nearer to death

He studied at the Capuchin College in Rochestown, Cork, and applied for entrance to the Capuchin Novitiate in August 1898.

His Easter Rising experiences are very dramatic, moving from early eyewitness status, tending to the dead and wounded in the dangerous Dublin streets and then ministering to some of the Rebel leaders on the eve of their executions.

"My part all through those two weeks was simply that of an Irish Priest; who I hope loved his Country and his fellow man; and was prepared to make his actions correspond with his profession. That was the capacity in which I played my part; and that is the role in which I write."

Good Friday (21 April)

"It was publicly announced that a Volunteer display on a large scale would be held at 4 o'clock on Easter Sunday, to which country contingents were being invited."

"It was ordered by Eoin MacNeill, as chief of staff of the Irish Volunteers ... [the last one had been peaceful] I felt no uneasiness about the matter whatever."

Easter Saturday (22 April)

"Seeing the great numbers of Volunteers who were approaching the Sacraments, 'acting under orders' as they said; gradually I became suspicious that there might be more than appeared on the surface ... I remember going to bed that night dreading what the morrow might bring."

Easter Sunday (23 April)

The Father Mathew Feis (Feis Maitiú) opened with "the customary concert."

"At the singing of some National songs, notably those by Gerald Crofts, one could not fail to remark that the air was surcharged with pent up feelings ready to be discharged and explode at any moment. Speaking together after the concert, we all agreed that there was danger of trouble ahead; though we little thought how near it was."

Easter Week 1916

Shots ring out (Mon, 24 April)

"Dinner had just finished about 12.25oc when a startling burst of firing rang out in Church Street."

"Trouble - I was prepared for. Yes a clash with the Police; or even with the soldiers; was possible. But a rebellion! Let me admit that the very thought never entered into my head."

Fr Columbus Murphy returned to the Feis at Fr Matthews Hall.

"The Dancing Competitions in connection with the Feis had been in full swing; and a couple of hundred children were present. Alarmed by the firing outside, some had come out to the door; and seeing the baby covered with blood, it is easy to picture the panic that ensued."

Rising confirmed (Tues, 25 April)

In the friary in Church Street, Fr Murphy learned of the extent of the uprising: "successful occupation of the different centres: The General Post Office, the Four Courts, the Mendicity Institute, Stephen's Green, Jacob's Factory, and even Boland's Mill was mentioned. Likewise the unsuccessful attempt to take Dublin Castle.

He was worried about his parents."My parents had come but two weeks before to take up residence at 60 Lower Mount Street, I was a little anxious about them.

"That night about 11 oc we were all startled by an outburst of firing. It seemed to be in the direction of Dublin Castle; lasted about two hours; and then everything became fairly quiet again. It was the first continuous firing that we had heard. It made a great impression on us all."

Street warfare (Wed, 26 April)

Fr Columbus Murphy set out for hospital early.

Just after breakfast "there was a deafening, crashing, thunderous report; a heavy gun in action somewhere. It was my first experience of big gun fire at close range; and I can assure you it was startling enough."

The British were pounding Liberty hall. He continued on his way through the city.

"I found that the Volunteers had now become very active and officious. Barricades had been erected in all streets; sentries were posted; and all persons going to and fro were stopped and questioned. They were looking for spies. Then I realised what street fighting meant ... the Volunteers were fighting street warfare."

Tending the fallen (Thurs, 27 April)

Father Murphy toured the city, trying to find anyone who needed a priest. He said mass early in the morning at Jervis Street hospital and found his parents "quite well, if a little alarmed".

As he passed through St Stephen's Green and past the Shelbourne Hotel, he observed that "there was no one to be seen anywhere, no sign of life. It was a weird sensation and feeling, as if one were in a city of the dead. The only noise was the sound of one's own footsteps, and the background incessant rumble of the firing."

He acquired the required military pass from the British at Dublin Castle that enabled him to pass through the streets, but was warned of the danger this posed for him, particularly with fierce fighting still in progress at the GPO.

Unconcerned, he proceeded to tend to the casualties of the war, giving spiritual succour and support. "For some time I was kept busy with the terrified who wanted to go to confession, as well as with the wounded and dying."

As he made his way back to Jervis Street hospital he witnessed the terrible toll the Rising had taken on the city centre: "one had a splendid view of O'Connell Street. What an appalling sight met my gaze. The far side of the Street, from the Pillar right down to the bridge, was a horrible devastated waste of burnt out buildings, ruin and desolation everywhere."

"The work between the wounded, the sick and the terrified was overwhelming; being more than even we could cope with. ... One had to attend the wounded; and oh such wounds. Soft, flat nosed bullets were being used that ploughed trenches through human bodies. One had to lend a hand to the nurses to remove the dead to make way for fresh cases that were arriving every few minutes. It was never ceasing."

Hoisting the flag (Fri, 28 April)

"As the soldiers were mostly English they naturally did not know that Jervis Street was an hospital. Now of all places two volunteers had taken up sniping positions somewhere on top of the private hospital, and there kept up constant fire for the four day. The consequence was the soldiers believed the snipers were in the hospital itself; and thus anyone appearing at a window was liable to be fired at."

"There was only one thing to do – hoist the Red Cross flag on top of the building."

He went out onto the flat roof with some medical student volunteers "when a bang, and a sickening thud of bullets flattening themselves on the chimney stack – startles us. We slowly recovered our breath, to find ourselves sprawling on the ground. That was a close shave Father – said he. Yes, we were never nearer to death." They eventually managed to get the flag draped over the side.

Beginning of the end (Fri, 28 April)

"It must have been somewhere around 5 oc pm that happening to be at the window, I saw an ignition shell land on top of the General Post Office and burst into flame. Immediately several men appeared and attempted to put out the fire. ... They seem to have been fired at and are taking cover ... Another shell falls, flames leap up; still another comes. Here are the men again; they make frantic efforts, only to be driven to cover again. The fire seems to be spreading – the flames are getting bigger. ... Soon the whole roof is a sheet of flames. Then I go down to tell the news – the General Post Office is on fire."

"Towards 9 oc pm the Post Office was a blazing cauldron of fire, nothing but the four walls standing."

Staying in the GPO was now unsustainable.

Surrender (Sat, 29 April)

Fr Columbus Murphy was still tending to the dead and wounded when the British Army came to the hospital and removed those "available men who had come from the Post Office."

The ramifications of the killings were starting to manifest themselves. Another, horrifying problem was beginning to emerge – there were "over forty dead bodies in the mortuary room. Some had been there from the Monday, and thus were beginning to putrefy."

"As we could get no outside help it was decided to dig a large grave in the plot, on the far side of the street behind St Mary's Protestant church, and bury them together."

A doctor delivered news that the fighting was over and Fr Murphy made his way back to the Friary – "a girl approached me with a paper in her hand. She said that she wanted to hand the surrender order to Commandant Daly, but how could she do it without being shot?" This was Elizabeth O'Farrell.

"Imagine then my position. I had nothing to prove the genuineness either of her story or of the document, except her word, and Pearse's signature. I did not know her personally, neither was I acquainted with Pearse's handwriting. Hence consider my responsibility if the whole thing was a forgery. On the other hand if her story was true, and the document genuine, it was my duty to do all I could to prevent further Bloodshed. ... I then asked her did she know Com. Daly personally? And when she answered yes; that decided me. I said I would bring the document to Daly; but she must come with me to guarantee its genuineness and prove to him the story was true. To this she agreed."

They both delivered the surrender to Com. Daly at the Four Courts. "To say he was surprised, is to put it very mild. He was horrified, stupefied with wonder. Remember since Thursday evening there was practically no communications from the different centres. He believed the fight was going well, and his stronghold was holding out wonderfully. But when we told him the true facts of the case, and the condition of O'Connell Street, he was convinced and said the only thing to do was to obey. He asked me would I negotiate the surrender with the military while he went in to explain matters to the boys."

Comfort (Sun, 30 April)

With many volunteers still disbelieving the surrender and refusing to follow suit, Fr Murphy was facilitated by the British Army to see Pearse and witness him rewrite the surrender.

"What a sad, forlorn figure. He was seated with his head bowed down, sunk deep in his arms resting on a little table ... tired, worn out, exhausted after all he had gone through."

Pearse rewrote the document, and Fr Murphy was then empowered to deliver it to the remaining centres of lingering resistance.

He witnessed prisoners, including Countess Markieviez, in Richmond Barracks and resolved to get an "access all areas" permit from the British so he could offer "comforting news of those who so far were alive and well. As I was the only one who saw the prisoners that day, I alone was in the position to give that assurance, as evidently no definite news of the wounded or killed was generally known as yet."

After the Rising

Hostility (Mon, 1 May)

"The city was in a state of suspense and indecision ... an air of fright and gloom and suppressed feeling ... the trend of public feeling that day and the next was decidedly hostile to the volunteers."

"I strove to intervene between the Government and the prisoners; to ameliorate their hardships, to soften their sufferings."

Thomas MacDonagh demanded to be "recognised as prisoner of war; and to get the rights of such." At Dublin Castle, Fr Murphy saw the Assistant Provost Marshall, who informed him that "they are only common rebels; and will be treated as such."

Executions (Tues, 2 May)

After 10pm, Fr Murphy was informed by the Governor of Kilmainham Prison that Tom Clarke, Patrick Pearse and Thomas MacDonagh were to be "shot at day-break". He ministered to all three men.

"How did they behave? Like men well satisfied to have attempted a noble task, sustained by the belief and conviction that they were justified in what they had done. Made serious and grave by the solemn approach of death; was only to be expected: but timidity or lack of courage, fear or cowardice, there was no vestige of such in any of them. I may admit that we who strove to assist them, had much more need of support to sustain us than they had themselves."

He was not allowed to stay with the men during their execution, against which he and another priest, Fr Aloysius, made a formal protest (to no avail). "Then off we went to the Friary to celebrate Mass for the repose of their souls."

The tide turns (Wed, 3 May)

"To my surprise I found that the Papers had the news, and blazoned forth its horror to the world. What a marvellous change was wrought by that announcement! A thrill of horror, and indignation, and fierce resentment pulsated through the city. They stood forth as heroes enshrined in popular estimation; and a paean of praise and admiration was heard on all sides. Yes the soul of Ireland had awakened as if by magic at the noise of those bullets; and the holocaust of their lives was not in vain."

Four more prisoners were to be executed (Edward Daly, Michael O'Hanrahan, Joseph Plunkett and William Pearse) and Fr Murphy attended to Edward Daly, who he knew personally.

"What to say? To encourage them, there was no necessity. To prepare them for death, they were quite ready. Merely then to receive a last message; to breathe a little prayer; that was all. Yet it was so callously informal the whole thing. Here they stood chatting with one another; with us; with the soldiers. There was none of that solemnity one associates with an affair of the kind."

"The Governor appears; mentions a name; gives the signal – ready. The prisoner shakes hands all round; then his eyes are tied behind his back; a bandage is placed across his eyes; soldiers take up their place, one at either side to guide him; and the Priest goes in front. As he reaches the outer door another soldier awaits to pin a piece of white paper over his heart. The procession goes along one yard, then through a gate way leading into the next. Here the firing squad of twelve men are waiting, rifles loaded. An officer stands on the left hand side, a little in advance; on the right are the Governor and Doctor. The prisoner is led in front, and there turned, faces the firing squad. The two soldiers quickly withdraw to one side; a silent signal from the officer; a deafening volley; he falls in a heap on the ground – dead. It is horrible, ghastly, disgusting, sickening. And thus the butchery goes on till all four are dead."

"I went to bed - yes but not to sleep; I actually felt sick with the callousness and horror of it all."

Father Murphy had to be evasive when asked questions the next day by the female prisoners he was tending to as to the nature of the volleys of shots they were hearing each morning - "it was difficult to answer questions without betraying oneself."

Leaving Dublin (Fri, 5 May)

No longer required in Kilmainham as official Chaplains were now attending, Fr Murphy resolved to leave on Saturday "to conduct a fortnight's mission in Inniskeen, Dundalk."

"When I got back there was now no need for my services. Everything was finished. Kilmainham was empty. The girls were all liberated. The Countess after due instruction in Mountjoy Prison had been received a Catholic. The men were mostly deported and in prison in England."

These pages are based on personal testimonies and contemporaneous accounts. They reflect how people saw things at that time and are not meant to be a definitive history of the period.

The words of Fr Columbus Murphy

Voices 16 objects

Voices 16 galleries

Credits

Extracts from Fr Columbus Murphy's memoir, and his image, feature by kind permission of the Capuchin Provincial Archives.

Additional thanks to Brian Kirby and Dr Conor Mulvagh.