Winifred Carney

A typewriter and a gun

"I place my typewriter and webley on the counter."

Revolutionaries, I suppose, ought not to have relatives

Winifred Carney from Belfast was at James Connolly’s side throughout the Easter Rising. She was his close confidant and typed his orders throughout the Rebellion.

"James Connolly honoured me with his trust and confidence in a way he did with no other person."

In the aftermath, she was imprisoned for her part in the Rising and only released almost eight months later following the general amnesty for untried prisoners. She returned to her family in Belfast.

After standing for election with Sinn Fein in 1918, she became a member of the Socialist Party of Ireland and, later, the Northern Ireland Labour Party.

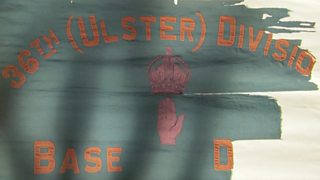

Through her involvement in the Labour movement she met her future husband, , a Protestant who had fought at the Battle of the Somme with the 36th (Ulster) Division.

Early life

Born in Bangor, County Down, in 1887, Winifred Carney was the second youngest of seven children born to a Catholic mother and a Protestant father.

When her parents' marriage broke up during Carney's childhood, her father left to live in London while her mother raised the family in Belfast, eventually settling at 2A Carlisle Circus close to the city centre.

Sarah Carney supported the family by running a sweet shop on the Falls Road, and Winifred was educated at the Christian Brothers' School. She became a qualified secretary and shorthand typist, securing a job as a clerk in a solicitor's office in Dungannon.

Adult activist

In her early twenties, Carney became involved in the Gaelic League, suffragist and socialist activities in Belfast together with her friend Marie Johnson, wife of the future leader of the Irish Labour Party, Thomas Johnson.

An important union

When Marie Johnson fell ill in the summer of 1912, she asked Carney to take over her work for the Irish Textile Workers' Union (ITWU) and introduced her to James Connolly, then the General Secretary of the union and later one of the leading figures in the Easter Rising. She joined the Irish Citizens Army and Cumann na mBan.

Aide-de-camp

Carney concurred with James Connolly's political ideas and became aware of his revolutionary plans in her capacity his personal secretary. She becomes his 'Aide-de-Camp' when preparations for the Rising began in April 1916.

"James Connolly honoured me with his trust and confidence in a way he did with no other person."

Easter Week 1916

An air of great activity

On 14 April 1916, Carney received a telegram from Connolly asking her to come to Dublin immediately. Throughout the period before Easter, she assisted with final preparations for the Rising, typing dispatches and mobilisation orders in Liberty Hall.

"Liberty Hall, the eve of the Rebellion. An air of great activity throughout the building. Connolly and Pearse are there."

On Easter Monday, Carney left Liberty Hall with Connolly and the Irish Citizen Army.

She marched to the GPO and was involved in its capture.

"We halt outside the G.P.O., Connolly giving the order, and we quickly march inside. He directs the Volunteers to clear out the staff and customers which they quickly do. In a few moments the staff appear from all over the building some of the women in an almost fainting condition. Soon they are gone and the doors closed. Two British officers remain. They are prisoners."

The GPO

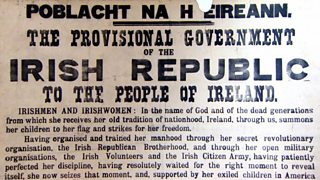

Winifred Carney was stationed in the GPO throughout Easter Week and witnessed first-hand the declaration of an Irish republic.

"When we have settled in to our occupation and the Tricolour floats from the Post Office standard Connolly takes me out to the centre of O’Connell Street to see the Flag of the Republic wave on high and we shake hands. Meantime the Proclamation is read by Pearse in front of the G.P.O."

Throughout the Rising she typed James Connolly's orders and observed the leaders in close-up.

"To keep up the morale of the men Connolly encourages the Volunteers to sing songs, many that they used to sing on route marches. I encounter Michael Collins coming down the stairs during this time and he sarcastically informs me if a piano is needed there is one in a room nearby. Ignoring his sarcasm I quite seriously reply that I do not think it would be needed. In these days, watching him move about with his hand thrust in his breast Napoleon like I think him sour and unimaginative looking as his remark seems to prove."

Evacuation

She was one of the few women in the GPO and, together with Elizabeth O'Farrell and Julia Grennan, among the last group to evacuate the building.

She initially refused to leave with the other women and insisted on staying with the wounded Connolly, protecting him until he was carried out on a stretcher.

" ... as he lay wounded, uncertain of his own fate that our next move would decide, he said to Pearse 'I want you to trust Miss Carney as you would me'."

Surrender

After the evacuation, the Volunteers eventually surrendered to avoid further bloodshed.

"The order for surrender has come. Mick Collins, his eyes red with unshed tears and apparently anticipating being sent to France as a conscript says to me 'by Christ I'll have revenge for this'. But I tell him that there are better men than him surrendering today."

Taken prisoner

Carney was eventually taken prisoner and spent Saturday night in the Rotunda plot along with other captured Volunteers.

She was soon moved by the British Army to Richmond Barracks and experienced the backlash to the Rising – the mood in Dublin was not sympathetic.

"With a double line of armed military we move off. Passing Christ Church, groups of poor women gaze at us in a frightened way and jeer."

Overhearing the executions

After a brief stay at Richmond Barracks, Carney was then moved to Kilmainham Gaol, where the majority of the executions of the rebels took place.

"In the early morning of May 3 I am awakened by the sound of firing ... My heart sinks for I know the first of the executions has begun ... But for many mornings to come we shall awake to that close noise of rifle firing and the crisp voice of the officer in command."

After the Rising

Capture and release

After her capture, Carney was initially interred in Mountjoy Prison before being transferred to Aylesbury with Constance Markievicz and Helen Maloney.

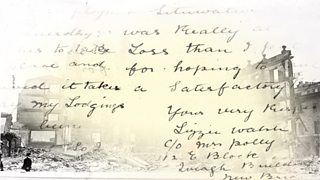

Her incarcaration left her concerned for the wellbeing of her mother, living alone in Belfast. "Revolutionaries, I suppose, ought not to have relatives."

Following the general amnesty for untried prisoners, Carney was released on 24 December 1916.

Sinn Fein candidate

Carney was elected as president of the Belfast branch of the Cumann na mBan in the autumn of 1917.

In December 1918 she stood as a Sinn Fein candidate with her own programme for a Workers' Republic but was defeated by Labour Unionist Donald Thompson.

She was the only female candidate (apart from Constance Markievicz) to stand in the elections.

Anti-Treaty

After the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the formation of the Irish Free State, she sided with the Anti-Treaty forces and was is arrested several times in connection with such organisations as the Irish Republican Prisoners' Dependents' Fund (IRPDF) and the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Labour of love

A committed socialist, Carney became a member of the Socialist Party of Ireland in 1920 and later, in 1924, the Northern Ireland Labour Party.

It was at a meeting of the NILP that she met her future husband, George McBride – a Protestant and an Orangeman who fought at the Somme with the 36th (Ulster) Division.

Grave issue

Winifred Carney died, aged 55, on 21 November 1943. She was buried in Belfast's Milltown Cemetery in an unmarked grave. Her grand-niece, Joan Austin reasoned that this was down to unhappiness from her brother at Winnie's union with George.

In 1985, a headstone was erected by the National Graves Association with the permission of George McBride and one of Winifred's nieces.

These pages are based on personal testimonies and contemporaneous accounts. They reflect how people saw things at that time and are not meant to be a definitive history of the period.

The words of Winifred Carney

Voices 16 objects

Voices 16 galleries

Credits

Winifred Carney's personal account is compiled from letters supplied by the (with thanks to Des Cassidy) and a pension letter courtesy of .

Biographical information is taken from the book with kind permission of its author, , who also thanks Joan Austin for new information on the Carney siblings.

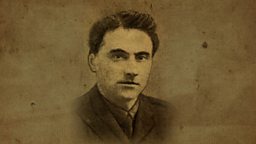

Image courtesy of Des Cassidy.