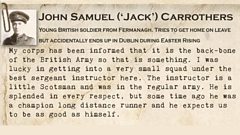

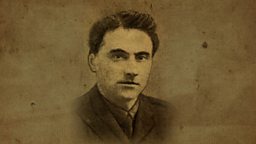

J S 'Jack' Carrothers

Stumbled into the Rising

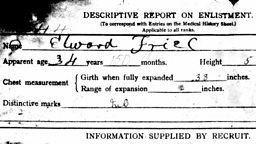

John Samuel Carrothers was born on 3 February 1898 in Tamlaght, County Fermanagh. Known as Jack, he was the youngest son of Samuel Graham Carrothers and Margaret Carrothers (nee Jamison) and had three older brothers.

I will wire from Dublin ... if the Post Office is open

Jack attended the Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, the same school that had once attended.

After leaving school, he worked for the Irish Land Commission Office in Dublin before joining the Army in 1915.

He soon applied to join the Officers Training Corps and was accepted on 15 December 1915.

This meant extensive training and studying in England in the early months of 1916.

Stuck in Dublin

Just before Easter, Jack is looking forward to going home for the holidays. He writes to his mother from London, ominously anticipating a slight delay in getting home through Dublin.

"I am afraid I will be stuck in Dublin until Saturday morning on account of Good Friday. ... I will wire from Dublin if I get that length, and if the Post Office is open."

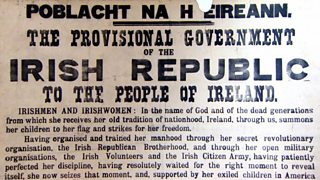

Easter week 1916

Hostilities, not holidays

As it turned out, Jack did not actually arrive in Dublin until Easter Monday - right into the heat of battle. His holiday at home was not to be.

His next letter home, written on Tuesday 25 April, struck a very different tone to his previous one.

"Dear Mother, arrived here last night and came straight to a Military Barracks. I will not be allowed out until the end of hostilities I suppose. At any rate the streets are most unhealthy on account of 'Sinn Fein' snipers and stray bullets."

Martial law imposed

By Wednesday 26 April, Jack seemed sure he would be in Dublin a while as the situation escalated. His letter home mixed updates on the action with the sort of reassurances any boy might offer his mother when living away from home.

"The Sinn Feiners are kicking up a fearful dust. Military law was declared this morning. I am stuck in Ship St Barracks and like all the other officers and men am living on biscuits and bully beef. However a big convoy of other grub has arrived so we are all right."

Unsafe streets

Although himself stationed within the barracks on garrison duty, Jack notes just how precarious things are in Dublin beyond those walls.

"The streets are by no means a healthy place for any one in uniform because the 'Sinn Feiners' are constantly sniping from the roofs. ... Ever since Monday night guns and rifles have been going constantly, and some bombs were thrown by the military."

"There must be an enormous number of people killed because it is a fearful thing to fire even a rifle in the City, let alone machine guns or artillery."

Boredom sets in

As Easter week wore on, for Jack the realities of battle became routine: "It is wonderful how soon one gets used to fighting. We lounge about here reading and yawning while volleys are being fired over our heads. It is very boring listening to crack of rifles all day."

Nevertheless, as he explained to his mother, these same realities made it somewhat difficult to conjure the most captivating missives: "I am writing it at intervals. Sometimes it is to see prisoners being brought in and sometimes to look at the effect of shell fire that I run off and leave it, so with these disturbing elements you can’t expect a perfect yarn."

Snipers shot

Jack does not spare his mother the details of his experiences in Dublin, writing in unflinching terms about an incident on Thursday 28 April.

"Two snipers appeared at a chimney quite close and we opened rapid fire on them, the chimney fell and also both the snipers. One was only wounded and he was brought in as a prisoner. His coat was covered with the blood and brains of the other sniper. A sight like this soon puts the notion of war out of one's head."

Celebrating surrender

On Saturday 29 April, news came through to Jack's barracks that the Rising was all but over.

"There is great a great cheering now, we have just been told that the Sinn Feiners have tendered an unconditional surrender, I suppose the 18 pounder artillery put the fear of God in their hearts. I will hardly get out till Monday as snipers are still firing ... probably the dead and wounded could be counted in thousands."

With the end of his stay in Dublin now in sight, Jack's thoughts turned to his likely next assignment: "I have seen enough of the horrors of war without going to France to see any more."

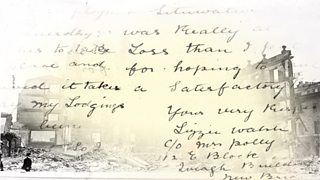

After the Rising

Dublin in ruins

Jack's letter home to his mother in the week following the Rising told of the devastation that had been visited upon Dublin.

"These barracks are part of Dublin Castle and it is the headquarters of the whole campaign. I was through the Castle today. It shows the traces of hand to hand fighting. The great marble staircases are torn with bullets and pools of clotted blood are at almost every door. Important papers are being tramped over and office accouterments are scattered everywhere."

"Sackville St, is half demolished by artillery. It is a great pity that it suffered so much as it is one of the finest streets in the world. The GPO is a thing of the past."

"There is a heavy smell about the city - the smell of blood and corpses."

"Dublin is certainly ruined."

Back in England

Jack finally makes it back to England on Thursday 4 May: "I arrived in London this morning and was very glad to be rid of Ireland ... I will send back some money if I go to camp, I spent very little in Dublin as there was no place to spend any."

By the end of June 1916, Jack was in a military training camp in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. In December that year, Jack got his commission - 2nd Lieutenant with the 3rd Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers.

Orders for France

In February 1917, Jack received his orders for France. He survived the Battle of Messines in June 1917.

He wrote home to tell his mother of his experiences there: "I came through without a scratch but my platoon lost very heavily ... I would not have missed this great battle for anything although it was a terrible experience and there were some terrible sights but looking at hundreds of mangled corpses does not worry me now."

Last letter

The final letter Jack Carrothers wrote to his mother was on 13 August 1917, from Ypres, and contained little startling news: "I have no special news as I have written so often. The weather is inclining to be raining again. Jack."

The next letter she received came a week later, from a Lieutenant Colonel with the news that Jack was missing after having been wounded at the Battle of Langemack. He had been killed in action.

These pages are based on personal testimonies and contemporaneous accounts. They reflect how people saw things at that time and are not meant to be a definitive history of the period.

The words of J S 'Jack' Carrothers

Voices 16 objects

Voices 16 galleries

Credits

Image and letters reproduced with the kind permission of Sam Carrothers, with thanks to the .