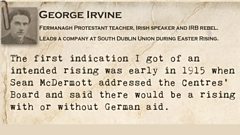

George Irvine

Protestant rebel from Fermanagh

Enniskillen born George Irvine was a committed member of the Church of Ireland who became passionately involved in the Irish language movement.

As I had only six men instead of 50, we had to do the best we could

Active in republican politics and a member of the IRB, he would lead a company through fierce fighting at South Dublin Union during the Easter Rising.

Court-martialed and sentenced to death, he saw his sentence commuted to ten years in prison.

Meanwhile, his brother William was serving in the British Army.

Fermanagh to Dublin

Born in 1877, George Irvine's parents ran a bible depository and bookshop in Enniskillen. George and his brother William were educated at the Model School and Portora Royal School, at which would later also be a pupil.

The brothers then attended Trinity College Dublin and settled in that city, George becoming a teacher. After the death of George's father, his mother and two sisters also moved to Dublin.

Language enthusiast

George became passionate about the Irish language: "I was a member of the Gaelic League which I joined in the year 1905." He was taught by Sinead Flanagan, later Eamon de Valera's wife, who became a close friend.

The Irvine family's return for the 1911 Census was entirely written in Irish, with some members listed as having the language, though two did not.

Committed church member

A committed member of the Church of Ireland, George was said to have attended church services wearing his Irish Volunteer uniform.

He also sought to bring his language and religious passions together by involving himself in the establishment in 1914 of the Irish Guild of the Church of Ireland (Cumann Gaelach na hEaglaise). This group's aims included the promotion of the use of the Irish language in Church of Ireland services, and "to provide a bond of union for all members of the Church of Ireland inspired with Irish ideals."

Joining the IRB

George says he was approached to join the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1907, but "I refused at that time to do so." He changed his mind within a few months, however, and on being approached again "I then joined."

He says he later became a member of the Leinster Council of the IRB.

Founding of Volunteers

Irvine says that he recalls that Cathal Kickham was "responsible for the starting of the volunteers ... He mentioned it several times at the Dublin Centres' Board of the IRB."

However, Irvine records, "the rest of us did not take him seriously, thinking it was some kind of a police force he wanted", until one night when he says Kickham explained, "'I don't mean a police force, I mean an army." That made us think and we began to discuss the matter."

It was finally arranged, he says, that their IRB Centre Chairman, Bulmer Hobson, and Seamus O'Connor should "get in touch with some harmless nationalists like Eoin MacNeill and D.P. Moran on the matter and see if it would be possible to form a committee to set things going. They ... were not to mention the IRB or use the word republican at all ... Simply to get an armed force to back up Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Rule, as the Unionists of the North had formed a force to oppose it. The committee was formed ..."

Irish Volunteer Officer

"When the Volunteers were started", Irvine says, "I became attached to B/Coy. [Company] 4th Bn ... When officers were elected I became 0/C. of the Coy. Eamon Ceannt became Bn. O/C when the 4th Battalion was formed."

This company, he says, was strongly affected by John Redmond's call for Irish Volunteers to join the British army and fight in World War One: "The Redmond split hit B/Coy, very badly. I had well over 100 men, about 130, and the split left me with about 50 ..."

Messages and meetings

By the early months of 1916, George was noticing increased activity in the ranks of the IRB:

"In March 1916, as far as I can remember, we had a very tense week ... when I left school each day I seemed to have lived on my bicycle carrying messages and summoning meetings ..."

Rebellion orders

Just before Easter 1916, George says, the company got orders: "Some weeks before Easter ... each Coy. [Company] received its orders and that was practically all it knew. B/Coy. was told to hold the back gate of the S. D. U. [South Dublin Union] to hold up an enemy ..."

The date set

Days before the Rising, Irvine gets word that it is definitely happening:

"The first definite news I got of the Rising was at a ... meeting on the previous Thursday ... [The Bray IRB member] reported he had been instructed by Patrick Pearse, some time previously, to be ready to cut the telegraphic cable when he would get word and he had got word that the following Easter Sunday was the day. The news came like a bombshell ... Hobson said he would see about it. He did not discuss it ..."

That night, however, Irvine says he's told to deliver notices for a meeting of their IRB Centre next day, Good Friday: "The business of the meeting was not stated, but it was evidently an attempt to stop operations. When we met at 12 noon Bulmer Hobson informed us that there would be no business, but each was to carry out any instructions he received regarding Easter Sunday."

But subsequently, Irvine records that he was told "that everything was settled ... Hobson was going to be placed in arrest and that [Eoin] MacNeill had been taken into the IRB. The Rising was to take place on the Sunday and the Germans were to land in two places - Kerry and Galway."

So, on Saturday, George made ready. His quartermaster was told "to distribute the emergency rations to the company", in preparation for the Easter Sunday rebellion.

Easter Week 1916

Cancellation and confusion

Irvine records that Easter Sunday brought more confusion: "We did nothing more until Sunday morning. The parade was to take place in the afternoon, and, about 11 a.m., an orderly called on me with a letter from the Chief of Staff ... an order to all officers not to turn out as the parade was off."

He says he then has this confirmed, but is told "the men were to stand by until 6pm. I carried out this order."

Easter Monday marching

Then, "on Monday morning, about 9 o'c. Martin O'Flaherty brought me an order from Comdt. Kent to turn out at Kimmage at 10 o'c. I sent Martin with an order to Sec. Comdr. Corrigan to mobilise his section and gave him the names and addresses of the men in the other two sections telling him to use any men he wanted to have them mobilised. Most of them had gone out expecting nothing to happen and only twelve turned up at Kimmage."

Later, however, Irvine says he discovered that bar two or three, all the men had turned out, "but linked up with whatever company they met."

Then, "we marched off from Kimmage about 12 o'clock to the South Dublin Union [S.D.U.]. At the back gate of the S.D.U. Comdt. Kent said he would take Lt Cosgrave and six of my men, leaving me with the other six. Three men from other companies came to me later so I had nine men."

Behind the barricades

Told "to take up a position in the huts inside the gate and barricade the windows", Irvine then sees British soldiers appear.

They start "to scale the wall around the S.D.U. and our men picked off a few of them. We found the huts mere matchboxes without any cover from fire, being made of thin wood."

Irvine says he then found himself cut off: "Later we tried to join Comdt. Kent in the main building but found we were cut off in that direction and one of the men, Paddy Morrissey, was wounded. We had to go back to the huts."

Surrender

Irvine and his men now come under very heavy fire: "We now occupied a back room in the hut we were in, but the British had closed in on us and in the evening were pouring volleys into the hut."

He says it's finally decided that their situation is untenable: "One man just beside me, John Traynor, got a bullet through his eye. I saw we could hold out no longer and asked the men would I surrender. They agreed and I did so."

After the Rising

Death sentence commuted

After the Easter Rising, George Irvine was court-martialed and sentenced to death.

This was commuted to imprisonment for ten years, and he was released in 1917.

Selected by Sinn Féin as a candidate in North Fermanagh in the 1918 general election, he later withdrew. He subsequently became Vice-Commandant of the 1st Battalion of the Dublin Brigade of the IRA, and after the Treaty, took the republican side.

A return to teaching

After the Civil War, George returned to teaching.

He died in 1954 and was buried with a firing party from Cathal Brugha Barracks rendering military honours.

These pages are based on personal testimonies and contemporaneous accounts. They reflect how people saw things at that time and are not meant to be a definitive history of the period.

The words of George Irvine

Voices 16 objects

Voices 16 galleries

Credits

Extracts from George Irvine's Witness Statement courtesy of the .

Thanks to Elizabeth Crooke at the Ulster University, Gordon Brand and Derek Davis for additional biographical information.

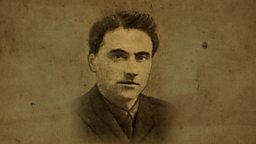

Image of George Irvine taken from the Catholic Bulletin, Vol. VII, July 1917 (held at the Linen Hall Library).