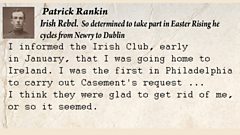

Patrick Rankin

Riding to the revolution

Patrick Rankin was born in Newry in 1889. A painter by trade, he became a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in 1907 "after two years on the waiting list."

We all slept the sleep of the just

He emigrated to Canada in April 1913, working in Toronto as a painter before moving to Philadelphia in June 1914.

There he joined the Clan na Gael (Irish Club), but also the City National Guard "to train and prepare for the future."

On his weekly visits to the rifle range, Rankin gathered spare ammunition – "by December 1914 I had accumulated over 600 rounds of Springfield ammunition in my lodgings."

Casement's rallying cry

About September 1914, Rankin said he was present as Roger Casement addressed "several hundred young Irishmen in uniforms" in Philadelphia, "telling them they would be needed soon and to prepare..."

Nothing happening in Newry

In early 1915, Rankin returned home to Ireland, smuggling in his stockpile of ammunition. He traveled to Liverpool seeking work shortly afterwards, but returns to Newry in March 1916, before conscription came into force. He did not think that his home was awash with revolutionary fervour.

"Things in Newry and district were very low as regards Volunteers or IRB. The people did not seem to care about such things, and there did not seem to be any meetings of these organisations or any preparations being made for the future."

Rising for real?

Rankin was informed that there was to be a Rising at an IRB meeting in Dundalk the week before Easter, although there was some uncertainty among the group as to whether the Dundalk report was genuine.

Rankin recalled that Robert Kelly, "for some years Centre for the IRB in Co Down", said he would "take no orders from Dundalk or Co Louth."

Easter week 1916

Arrival at the Rising (Tues, 25 April)

After a frustrating few days shuttling between Newry and Dundalk trying to ascertain whether anything is happening with the IRB, Rankin satisfied himself that something was afoot in Dublin. He was so determined to be involved that he cycled the 65 miles from Newry alone.

"It rained very heavily from I left Balbriggan until I arrived in Dublin about 7.30pm. (I carried a six inch revolver on my journey and fortunately, I was not stopped by the police."

In Dublin, Rankin stayed with his sister and brother-in-law, who did not share his passion for the cause. "My brother-in-law was keeping a close watch on me." During the night, his revolver and ammunition disappeared.

Journey to the GPO (Wed, 26 April)

Rankin slipped out of his sister's house with some subterfuge, claiming he was going to clean his bicycle in the yard before jumping the wall.

He is soon stopped by British soldiers, but avoids suspicion and even manages to get directions to Parnell Street. There he finds a large crowd gathered and manages to get himself into the GPO.

Having presented himself for service, he was issued a Lee Enfield rifle and ammunition by Henry O'Hanrahan, someone Rankin considered an unlikely combatant – "one could imagine him more at home in a library of books" – and assigned sentry duty on the roof.

"We were to watch for any enemy approach on the GPO, especially during the night. About one o'clock in the morning a Dublin man, who was in charge of us, asked me to look out between the stone balustrades of the roof facing O'Connell St and see if any enemy were coming. I had only time to draw back to my position when a bullet grazed his ear and mine, it was a very near shave."

Preparing for the siege (Thurs, 27 April)

Ordered down from the roof to prepare for a siege, Rankin carried bags of coal "to serve as a barricade in event of an attack. ... No sooner had the barricade been completed than shells began falling on the GPO, starting numerous fires."

Overnight the men in the GPO had to make do with beds of bricks and mortar, but "we all slept the sleep of the just."

Move to Moore Street (Fri, 28 April)

Rankin spent most of the day in the GPO attempting to quell fires and stop them spreading. He volunteered to go to GPO basement and remove "grenades and other inflammable articles" from the fire. "The basement of the PO was like a lake of water which collected from the hoses used to put out the fire."

Ordered to move to Moore St, Rankin and the others are "met by rifle fire from the enemy." Speaking of a young volunteer, he says – "As he moved past me he shouted 'oh, my God' and fell in my path. I caught him in my arms, but he was dead in a minute, shot in the centre of the forehead. I laid him down on the path and said a short prayer."

Surrender (Sat, 29 April)

"On Saturday evening we were told by one of our own officers whom I did not know and who carried a white flag, that we were to come out and surrender. We were marched out to O'Connell St and halted between Parnell Statue and Nelson Pillar facing the Gresham Hotel where each Volunteer laid down his arms and ammunition in front of him."

Rankin was then inspected by a British Army officer (who "called me a dog") before being moved to the Rotanta hospital. He described the officer in charge there as "dressed in Khaki and very drunk", issuing orders to his sentries such as "if any Volunteer stood up or went on his knee he was to be shot."

Dublin lets loose (Sun, 30 April)

"When morning came there were three or four of my companions lying on top of me and others likewise. The church bells were ringing, calling the faithful. An old woman passed by saying 'God bless you, boys.' I thanked God for one kind person that morning."

By the afternoon, not much sympathy was to be found. Around noon, the prisoners were marched out of the Rotunda under guard to Keogh Barracks.

"Dublin's worst was let loose from their stockades, the women being the worst. They looked like a few who were around during the French revolution. ...The women were allowed to follow our men to barracks, shouting to the soldiers 'use your rifles on the German so and sos'."

"Inside the English soldiers came along to meet our men telling us we were all going to be shot and to hand over any money or watches, I am sorry to say quite a few fell for this mean trick."

The men were then marched to the quays to be put on a boat bound for England. "We were packed like cattle in all parts of the boat and we got a hostile reception when we arrived at Stafford. Of course, what could we expect from our enemy’s people."

After the Rising

Stafford prison

On 1 May, Rankin was held in Stafford prison in solitary confinement for four weeks in very cold conditions, his property confiscated.

Thereafter, he was allowed to congregate with his fellow inmates. They had a kindly sergeant married to a Dublin woman and allows them to sing Irish songs whilst scrubbing floors.

Sent to Frongach

In July, the Stafford prisoners were sent to Frongach internment camp in Wales. Michael Collins was a fellow internee.

At Frongach they held Irish classes and dances and had books in which to write down "songs and satire of the camp dealing with 1916."

The volunteers were then brought to London "to be tried by a Commission set up by the English Government. This was only a farce and a waste of time and money ... we were examined and tried and returned to Wales."

Finally free

At the end of August 1916, Patrick Rankin was discharged from Frongach and returned to Newry.

He subsequently served as the Officer Commanding of the Newry Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the War of Independence (1919-21).

Patrick Rankin died on 17 September 1964, leaving behind a wife and five children.

These pages are based on personal testimonies and contemporaneous accounts. They reflect how people saw things at that time and are not meant to be a definitive history of the period.

The words of Patrick Rankin

Voices 16 objects

Voices 16 galleries

Credits

Patrick Rankin's account courtesy of a witness statement originally recorded by and reproduced with the kind permission of .

Image reproduced by kind permission of Patrick Rankin's grandson, Joe Murray.