Leslie Bell

Wounded at the Somme

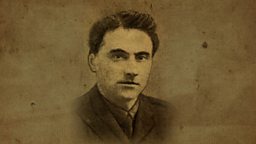

Leslie Bell was born c. 1897 to a farming family in Moneymore, County Londonderry, the son of Thomas and Marion Bell.

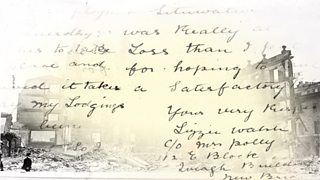

I was thinking it would be milking time now at my father's farm

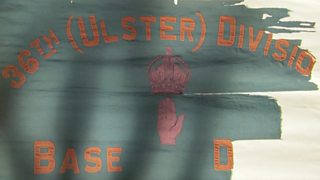

Educated at Cookstown Academy, Leslie left school in June 1914, just before the outbreak of World War One, and enlisted with the 10th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, 36th (Ulster) Division in September 1914.

After training, and arrival to France, in his testimonies he vividly describes his 1915-1916 experiences of trench life. Then came the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

Of it, he recollected, "it was a very lovely morning, very warm, we were told that all we had to do was slope our rifles ... light your cigarette and march on ... but to us it didn’t seem so simple. Because we knew that we were up against something that we didn't know anything about ..."

But as his wave went over the top, a "shell lit, nearly knocked out and killed all the platoon. And I got wounded. Back of the legs ... I lay on the battlefield from that till about four o'clock in the evening ..."

Evacuated to England for treatment, Leslie subsequently was treated at a hospital at Holywood, Co Down.

Demobilised in 1919, Leslie returned to civilian life in Moneymore, where he spent the rest of his life. He died on 11 February 1995, aged 98.

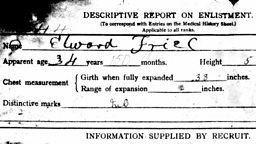

Enlisting underage

Leslie Bell had been, he says, "an Ulster Volunteer", and though officially too young to join up, then being aged just sixteen, he says he was keen to join the Army.

His parents were not keen: "My parents didn't like it when I told them that I was joining up." However, he recollects, he "decided to join up for the fun and excitement." He says he and twenty two others left Moneymore to enlist on 5 September 1914, and "Quare fun it turned out to be!"

Joining the 10th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers in September 1914, Leslie says "I didn't tell them my exact age you know."

The teenager found himself in a uniform that didn’t fit: "The uniform was too big for us. You had to alter it so that it would fit you."

Undergoing training at Finner Camp, he worried that he would never reach France: "We didn't think the War would last long enough for us to get to France. We thought it would be over by Christmas as the stalemate of the trenches hadn't set in yet."

Trench life in France

Leslie finally departed with the 10th Royal Inniskillings for France on 5 October 1915 as part of the 36th (Ulster) Division.

He says that "The closer we moved to the front, the louder we heard the guns. It was then we started to get worried."

Leslie described some of the difficulties of trench life in 1915 and 1916, until the Battle of the Somme on 1 July: "the winter was quite a severe winter, freezing and snowing on us."

"I remember when you were on duty on the parapet the only amusement was putting a bit of meat or biscuit or something on the end of the bayonet and there were big rats come along and eat it off the bayonet. So you got the rat eating off the bayonet, you pulled the trigger ..."

Other problems, he says, included lice: "... the lice was eating you. Well then in your spare time ... you mostly sat down, took off your shirt, and started to kill lice. And the best way to kill lice was to light your cigarette and run it up the seam of your shirt."

Work, he recalled, was tough: "You were working and knocked hell for leather during the day and then out doing working parties at night. Putting up wire was the worst job. It was no joke going up on a winter's night with a big freezing roll of barbed wire on your back, laden down like a pack mule. Then out over the trenches out to your wire in no-man's land. The slightest noise could have got the German machine–gunners to open up. At least in the trenches you knew what you were doing and you had some protection."

1 July, into battle

Before 1 July, Bell says the men practiced constantly: "You could have attacked those positions with your eyes shut we had practiced it so much."

He says: "So we stayed there till the first of July. And then on the first of July it was a very lovely morning, very warm, we were told that all we had to do was slope our rifles ... light your cigarette and march on."

"But it was alright for these men nearly fifty mile away sitting in the armchair with their glass of brandy in their hand it seemed simple enough but to us it didn't seem so simple."

Because we knew that we were up against something that we didn't know anything about. So ... the guns stopped, the whistle went, and off we went."

Before zero hour, he says "I was thinking it would be milking time now at my father's farm at Moneymore and everything would be lovely and peaceful."

But, he says, after the whistle blew: "The first two waves they were cut down before they got out of the trench ... I was in number three or four ... I got about fifty yards up to the barbed wire when the shell lit, nearly knocked out and killed all the platoon."

He himself was injured: "I got wounded. Back of the legs. That was on the first day ... I lay on the battlefield from that till about four o'clock in the evening ..."

But Leslie recalls he was still being pressed into action: "Captain Robertson was running up with his Platoon and as he ran past, gave me a kick to see if I was still alive and shouting for me to come on. I was lying on my side and watched him and the other advance, until a shell burst above them and downed him and some of his men."

Dumped among the living and the dead

Leslie says he was eventually picked up, and taken by ambulance to the dressing station, where the "soldiers was lying on the floor on stretchers ... I was dumped in among the living and the dead ..."

Next day he describes being sent to a hospital at Étapes. He was subsequently sent back for treatment first to England, and then to Holywood, Co Down.

Aftermath and later life

After duties away from the frontline from November onwards, Leslie was eventually demobilised in January 1919. He returned to his home town of Moneymore, where he died in 1995 at the age of 98.

Of his wartime experiences, Leslie Bell reflected:

"I wouldn’t like to think that anybody would have to stand in the trenches again, with the sleet and snow and up to their knees in water, I wouldn't like ... any young person to have to come through that ..."

These pages are based on personal testimonies and contemporaneous accounts. They reflect how people saw things at that time and are not meant to be a definitive history of the period.

Voices 16 objects

Voices 16 galleries

Credits

Thanks to Gardiner S Mitchell, for image and permission to quote from Three Cheers for the Derrys! A History of the 10th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers in the 1914-18 War Based on the Recollections of the Final Veterans (YES! Publications, 2008), for which Leslie Bell was interviewed.

Thanks to for permission to cite from their oral testimony of Leslie Bell.