Breakfast with the monks at 3600m

Words – Justin Anderson

Photographs – Justin Anderson and Susan Gibson

A young monk appeared on a balcony and high above the world he began the call to prayer.

While on the quest to film snow leopards, the Planet Earth II 'Mountains' team were lucky enough to visit 500 year old Thikse Monastry and share morning prayers with the monks there.

The monastery loomed out of the half light, a huge jumble of white washed ramparts high above on a rocky crag. Once inside we crept quietly through the courtyard, all still and no one to be seen, the monks still sleeping. We headed up to the roof. The steps were steep and the thin cold air burnt our lungs. But it was worth it. The view over the houses and across the Indus Valley to the mountains beyond was breathtaking in the other sense. The first light of the sun painted the summit of Stok Kangri before creeping ever lower, across the range and finally over the valley floor to the monastery. Its rays were welcome, my toes were stinging with the cold and my finger tips numb.

A young monk appeared on a balcony and high above the world he began the call to prayer. The striking of a metal rod on rock, chimed out the same call that had been issued from these walls every morning for over 500 years. The sleeping dogs began to bark. Buddhist monasteries often host a large number of them and Thikse was no exception. It is said that dogs are reincarnations of monks who did not do their duty well, so they are tolerated and given a warm home by the living. Slowly the monks emerged. Small boys hurrying, yawning, their breath frosty clouds in the cold.

They left their shoes scattered outside the huge ornate door and headed into the prayer room. One last monk, the oldest, came up the steps, puffing and blowing as he struggled to keep up, not wanting to be late. He smiled at us, his face erupting into an enormous grin. ‘Julay!' He greeted us. We followed him in and took seats by the door.

All was silent, then tea was served, the smallest boys hurrying, slipping in their socks as they carried huge kettles along the rows, filling up the monks' bowls.

The prayer room was overwhelming to the senses. Most powerful was the smell of old socks and butter tea, making it a little like a boy’s school changing room.

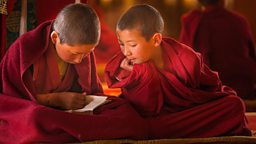

The large room had an elaborately painted ceiling, with swirling rainbow coloured murals of demons, dragons and lions; celestial battles from before the time of man. The ornate roof was supported by pillars from which were hung silken thankas – Tibetan religious paintings – and banners. Beneath were four rows of long cushions, where the monks sat cross legged. The oldest in his 80s, the youngest about five.

The abbot came in wearing yellow robes, pausing to put on his upright hat that reared up from his brow like a wave about to break. This was the sign of a 'yellow hat’ monastery, meaning these monks were from the Gelukpa sect, devout followers of the Dalai Lama.

All was silent.

Then tea was served, with the smallest boys hurrying, slipping in their socks as they carried huge kettles along the rows, filling up the monks' bowls. The steam curled up from the bowls as the monks eagerly sipped, slurping the hot tea.

Older boys then came along carrying silver buckets, emptying out spoonfuls of tsampa barley which, with more tea, was added and stirred into a thick porridge. It was a little voyeuristic as we watched them eating breakfast, our own empty stomachs starting to rumble. The monks began to chant, reading sacred lines from thin strips of paper they had unwrapped from silk bindings.

At times they called a repetitive mantra, at others a rising melodic chorus, then like a storm hitting the mountains, the calm was broken by the crashing of symbols, the cue for rapid drum beating and a bass rumble from two long horns. Finally the ear piercing, high pitched single horn; the lightning, playing out the same two notes, repeated faster and faster to a rising crescendo.

My toes were still freezing and I tried not to fidget too much in the cold, rubbing them between my fingers to get the blood going.

Then all would become still before the whole cycle started over again and again. It was hypnotic.

My toes were still freezing and I tried not to fidget too much in the cold, rubbing them between my fingers to get the blood going. The monks seemed impervious to the frigid temperature, all wrapped up tightly in their red blankets. Only the smallest boys sat shivering. Despite its up front formality the ceremony was really pretty relaxed. The boys whispered and chattered, even through the most solemn moments in the ceremony. Only once did the abbot raise his finger to warn one small boy, whose giggling had gone too far.

More tea and more tsampa came along the rows, the boys rolling it with their fingers around the bowl until it formed a pastry like cake, which they broke off pieces to chew on. As the musical storm rose up for the umpteenth time we left. Happy to have witnessed the most amazing of breakfasts and keen to go and find our own.