Extreme conservation: Tough decisions to save a species

By Steve Murphy, Conservation Partners

Conservationists regularly make decisions that favour one species over another. Feral cats – for example – an introduced species that kill billions of native Australian animals every year. Removing them to save native wildlife is a relatively easy, albeit unpleasant, decision to make. But what if one native species is causing significant problems for another that is imperilled, what – if anything – should we do about it?

I work for a non-profit organisation called . We assist farmers and other landholders to protect natural values and save endangered species. One of our main projects is saving golden-shouldered parrots on Artemis Station – a 125,000 hectares cattle farm in northern Australia. On Artemis, we are forced into actions that favour the parrots over some other native species. By no means do we enjoy this ‘extreme conservation’, but it is essential because the future of these extraordinary birds is on a knife edge – let me explain why.

An ecosystem out of balance

Golden-shouldered parrots rely on open grassland habitat for food and nesting sites but these savannahs have disappeared from large parts of their range due to a process called ‘woody thickening’. Certain modern-day grazing and fire regimes can allow young trees to establish and grow quickly. This process has caused vast areas of natural grasslands and sparse woodlands to change into dense thickets. In turn, predators colonise and hunt very effectively due to the increased cover.

Female parrots are especially vulnerable to attack because they do most nesting duties, including nest cavity excavation and incubation. Typically, when a female golden-shouldered parrot attends the nest, her male partner sits nearby keeping watch for predators. But if the habitat is too thick, males often fail to detect predators fast enough to sound the alarm, often with mortal consequences for the females. Indeed, our monitoring shows that females live for only about half as long as males. This often has disastrous knock-on effects.

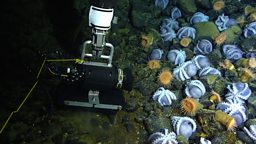

Whilst the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ crew were filming at Artemis, they witnessed the consequences of what often happens when a single parent is left to attend his nest. Being alone, the male struggled to keep up enough food for his large brood, and so when the smallest nestling died of starvation, meat ants attacked and not only consumed its body, but its living nest-mates as well. A tragedy for the population with so few parrots remaining.

An ecosystem reset

The solution to all this is plain to see: manage these habitats so that they return to an open structure and so reduce predation risk. But this is much easier said than done.

Research shows that even aggressive grazing management and high intensity fires do little to reverse severe cases of woody thickening. Instead, trees have to be physically removed. This makes our work different to many conservation efforts where the loss of native trees is the cause of species’ decline. In our case, we’re clearing native trees to save a species.

And so, we’re removing thousands of trees to reset parrot habitats back to an open state. We can’t use heavy machinery because we could damage the termite mounds within which the parrots nest. So it’s all done by hand. Since 2021, we’ve restored about 60 hectares of parrot habitat. It’s been a big effort but our data show that nests are more likely to do better if they are situated in a restored area. However, it’s going to take another five to ten years before enough habitat is restored that will support broader population recovery. We worry that this is too slow and that by the time we’ve restored enough habitat, the parrot population may have dwindled to such low numbers that recovery could be impossible.

Until the habitat restoration catches up, we’re using two emergency actions to secure and grow the remaining parrot population. The first relates to the heartbreaking story of the meat ant attack witnessed by the Planet Earth film crew. In 2022, 19% of parrot nests failed because of meat ants. With parrot numbers so low, we can’t afford to lose this many nestlings, even if the cause is a native species. In early 2023, we began carefully using targeted poison at nests where nearby meat ant activity is high. We didn’t lose a single nest to ants in 2023, and so we’re confident this action will help get more baby parrots into the population in the future.

Our second emergency action uses small electric fences to exclude land-based predators, such as monitor lizards, tree-snakes and feral cats. The fences deliver a powerful but non-lethal shock to any would-be nest robber. After a rapid deployment, late in the 2023 breeding season, their success was clear to see. Those nests protected by an electric fence incurred no losses of chicks and so added 23 new parrots to the population. Given such positive results, subject to funding, fencing and ant control is set continue over the next few years and we cautiously expect to see even more young parrots entering the population.

Nobody, including us, likes extremely interventionist conservation management. One of the things we all love about nature is the way ecosystems function to maintain wildlife populations more-or-less in balance. We don’t like killing native trees or preventing native predators from doing what only comes naturally to them. But when the situation gets way off-kilter, as it has with golden-shouldered parrots, we really have no choice but to intervene. To do nothing creates the very real possibility that golden-shouldered parrots will follow their cousins, the paradise parrot, into extinction.

Web exclusive: When meat ants attack

A male golden-shouldered parrot tries to defend his nest from meat ants in Australia.