Filming treehoppers in Ecuador

By Abigail Lees, director for Forests

Yasuní National Park in the Ecuadorian Amazon is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet.

one of the most biodiverse places on the planet

That's where photographer Javier Aznar Gonzalez de Rueda, cameraman Howard Bourne, and I came to search for the treehoppers. We were armed to the hilt with a breadth of research about this odd family of insects diligently uncovered by Assistant Producer Alex Walters.

Treehoppers range in size from roughly that of a £1 coin, or quarter dollar (like the C-shaped treehopper in the photograph at the start of this article), to ones that are so tiny they can sit on top of a pin head.

We filmed an array of colourful treehoppers, all with interesting, and often elaborate headdresses. They mimic other objects or living things, such as thorns, or even ants, to blend in with their surroundings- an effective strategy to hide from predators.

But this is not the most amazing thing about them. They have a hidden language. Treehoppers communicate with one another by vibrating their abdomen against the stem of the plant they are on.

We brought specialised equipment to tap into this rich world. We clipped a super-sensitive sensor onto the branch, which picked up the vibrations. An amplifier attached to a recording device allowed us to listen in on a variety of calls from several species.

I was transfixed.

Now I’d tapped into this secret treehopper world, I couldn’t go back.

One species sounded like an oinking pig, another like mournful whale-song, another as if an entire drum circle had assembled on the thin little twig, and yet another like a zapping gun sound effect from an old school computer game.

We enlisted the help of insect communication expert Professor Rex Cocroft at the University of Missouri to help with the identification of each treehopper we filmed and to match up their unique sounds.

He also told us if the song had a meaning: to warn others about predators, signal the presence of food, or even a courtship display.

Now I’d tapped into this secret treehopper world, I couldn’t go back. We came here to film a fantastic interaction between a mother Aetelion reticulatum treehopper and her young (nymphs), as well as their bee ‘friends’.

The mother of this species will actively defend her fifty or 100-odd nymphs from predators. Mum and young communicate with one another using vibrations, but it also looks like they signal visually by waving their arms like an air traffic controller if a predator comes too close.

I observed the nymphs doing this whenever a spider or an assassin bug came into range. Mum was able to swat away ants with her formidable appendages, giving her the nickname ‘kick-ass mum’ or ‘ninja mum’, but some predators were too big for her. This is where the bees came in.

Our eyes were glued to this single branch for three weeks, watching mini dramas play out before our eyes, and becoming more and more enamoured with this amazing bug extended family. The bees were actively defending the treehopper mum and nymphs from predators. It was a fantastic example of two different animals ‘helping’ one another.

And what did the bees get out of this? Well, the primary diet of treehoppers is sap from their host plant. Bees love this sugary treat, so the treehopper nymphs would exude honeydew from their behinds as a reward to the bees for their protection.

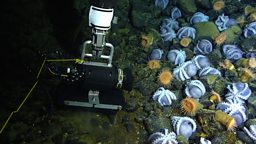

Treehopper insects pay bees to protect them

Bees protect treehopper broods from an assassin bug in return for honeydew.

While we were transfixed on this microcosm, we’d often be snapped out of our trance with a bang. Something had bumped the tripod and sent our image of the tiny treehoppers swaying.

He followed us everywhere (even to the toilet).

It was none other than an Amazonian tapir, one of the largest animals in South America. Often known for being reclusive and night-time wanderers, they are very difficult to see in the wild. We felt honoured by this grown male’s visit to our place of work.

He was a charming animal, and very, very curious. He took a liking to the tripod, and more than once we had to ask him to stop chewing at it.

He followed us everywhere (even to the toilet). He swam alongside our boat in the evenings when we left for camp. Howard likened him to a Labrador dog. I could certainly see the resemblance.

One evening Howard and Javier were taking their evening bath in the Tiputini River when a monster emerged from underwater.

The great thing surfaced right in-between Howard’s legs, causing the eco-soap to slip from his hands and into the water. Plop! It was the part-Labrador part-tapir. Perhaps he wanted to partake in bath time, too?

Through observing animals over long periods, nature documentary film crews often become enamoured with their filming subject. But there are so many other mini and massive creatures we meet along the way that don’t make it onscreen.

I left Yasuní with a newfound appreciation of the bizarre interactions I had witnessed: secret sound languages; insect mothers displaying maternal care; bees and treehoppers as allies; and a firendly tapir! And of course for the people I shared those special moments with.