To the ends of the Earth

By Nick Easton, Producer/Director for Coasts and Freshwater

Could we even film a species for the first time?

Starting work on Planet Earth III is a daunting prospect. You ask yourself, are there really new places to travel to? Can we find new dramas to tell? Could we even film a species for the first time? The answer is, of course! The natural world never ceases to surprise even us wildlife filmmakers. But capturing it is no mean feat.

New technology is a key part of the toolkit that can help us shed new light on the natural world. Whether that’s using thermal cameras, now equipped with telephoto (i.e. long lens) capabilities, to reveal hungry lions struggling to hunt seabirds at night on the shore in Namibia. Or using our own specially-built rigs, such as ‘whale cam’ - developed over many months in consultation with scientists. We made use of advances in camera miniaturisation and a willing human guinea pig in a swimming pool in Bristol to develop something we could attach to a whale and reveal their home in Argentina as never before. (both sequences in episode 1, Coasts). What we didn’t expect was how hard it would be to get a shot without our own crew in…! The curious whales kept turning back to our boat.

At the other end of the scale, our smallest subjects require a different approach. Tiny animal dramas are very difficult to capture in the turbulent world of, for example, the ocean or a blustery treetop. Take the sea angel (episode 1, Coasts): no bigger than your little finger and often smaller, they can be swept out of frame by the slightest of underwater currents. To capture these animals hunting, we collaborated with an extraordinarily dedicated arctic scientist and cinematographer.

In episode 5, Forests, we drop in on the everyday drama of a tiny insect called a treehopper. Treehoppers are even smaller than sea angels, and a breath of wind would blow them in and out of the focus of our cameras. And in extreme close-up, the gently moving dappled light of the forest is magnified into a chaotic, unwatchable flicker.

But these incredible insects are specific to a single host tree, so we have no option but to film them in situ. So we control the factors that we can, using portable lamps to create a constant light source and sheltering the branches from wind and rain so we can capture these extraordinary insect stories on location in the wild.

Episode 2, Oceans, features a raft of species (pun intended) that are, literally, invisible to the human eye. Microscopic plankton are one of the most overlooked and important species in the ocean, and indeed on the planet.

We collaborated with a scientist to capture images of these extraordinary, alien-like animals on specialist microscopes, using advanced imaging techniques. The magnification is so great that not only can we see these single-celled animals, some of them as small as a few microns, moving through the water, but we can also see their ‘organelles’ moving inside them too.

Invisibility comes in different forms. Episode 7, Human, features a camouflage master: the tawny frogmouth, a bird that looks to be part-owl, part-log. To track down these cryptic creatures, the team did a radio station shout-out to reach as many citizens as possible who may have encountered them in their own gardens. It took weeks to sift through the thousands of responses and find the most interesting and suitable urban nesting spots of these well-disguised nocturnal birds.

For Planet Earth III, we also made use of new developments in aerial drone technology. In episode 6, Extremes, we reveal the cathedral-like expanse of Hang son Doong in Vietnam – what is thought to be the world’s largest cave. Filming without causing damage to this fragile place, which was only discovered in 2009, required a specially-adapted ‘heavy lift’ drone, carrying a huge light array.

This cave extends for many kilometres underground, so the process of hand-carrying each piece of equipment into place took days. But the real challenge came in flying the heavy lift drone in synchrony with a second, more conventional filming drone without crashing - both into each other and the cave walls. The ensuing aerial dance was carefully choreographed and coordinated by a team communicating on walkie-talkies hidden in the shadows.

But so often capturing a new story is simply a question of time

Filming drones are also getting smaller and more discrete. This means we can get closer to animals without disturbing their behaviour, but it also allows us to take them to new places entirely. In episode 7, Human, we show the sci-fi interior of a so-called ‘vertical farm’ in the US. Every single piece of equipment had to be sterilised before entering the precisely controlled growing space. Filming was done on a drone that can sit in the palm of your hand but, amongst the tightly packed growing produce, the expert pilot still only had centimetres to spare each side of his rotor blades.

But so often capturing a new story is simply a question of time… lots… of… time. In episode 4, Freshwater, we’re witness to the cunning and patient hunting method of mugger crocodiles, in what must be one of the tensest four minutes of the series. But the crocodiles’ patience had to be met by that of our camera man Abdullah, who spent a total of 300 hours in the hide. For the first 100 of these hours, nothing happened at all! Abdullah claims to have learned to sleep in five-second bursts to maintain his sharpness. The action could happen at any moment, and without warning. All we know is that he got the shot.

In episode 6, Extremes, some of the most haunting images of the series feature the wolves of Ellesmere Island, high in the Canadian Arctic. Filming them was an endurance test for the crew, who undertook a shoot more than two months long. The crew were forced to pull out a couple of weeks ahead of schedule when winter looked set to arrive early. Even then, they had to clear rocks by hand from a makeshift runway on the tundra for the incoming plane, to ensure their safe return. The result is a unique insight into the tough lives of these Arctic predators.

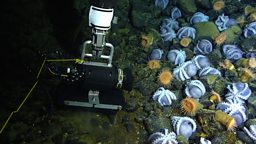

But perhaps the most extraordinary tale of endeavour comes - believe it or not - from a spare room in Bristol. When Covid struck, we continued filming whenever and wherever we could safely do so. That’s how my fellow producer, Will Ridgeon ended up directing a remote, robotic submersible that was two miles under the ocean and over 5000 miles away from his makeshift office. The unfolding story of an octopus aggregation, and some extraordinary parental dedication in the deep sea, is something that will stay with you for a very long time.