Saving the world’s rarest freshwater dolphin

By Uzma Khan, Wildlife Biologist, WWF

Locally known as Bhulan, the Indus river dolphin is the most endangered freshwater dolphin species in the world. It is native to the Indus River system, with the only viable population existing in Pakistan. The Indus River, where it lives, also supports millions of people, and its waters are used to irrigate an area the size of England. Tragically, these dolphins can become stranded behind the vast networks of dams and man-made canals and must be rescued. I am honored to have played a role in the conservation of this special animal, and it all began with my first inspirational experience over twenty years ago.

the Indus River dolphin is the most endangered freshwater dolphin species in the world

When I set out in 1999 to see my first Indus river dolphin, the species was heading for extinction. I was WWF’s education officer at Lahore Zoo and heading for an experience that would change my life – and help to change the trajectory of an entire species. After a short drive from Sukkur airport, I found myself next to the Indus River, a truly mighty river, controlled by an equally mighty barrage, which somewhat dimmed the natural splendour.

I had difficulty sleeping that night due to the anticipation of the next morning's visit to Rohri Canal to witness my first sighting of the Indus River dolphin. At that time, we lacked social media and there were no documentaries about the Indus dolphin, all I had seen were pictures, so my mind was a blank canvas. We arrived at the canal bank and I caught my first glimpse of this elusive creature. It surfaced - and then disappeared as quickly as it had emerged, but it was love at first sight - My first ever encounter with any wild animal in its natural habitat! However it was bittersweet. Witnessing this dolphin trapped in a canal, relying on our assistance for rescue, transformed my perspective. The excitement that had built up in the preceding weeks morphed into a mixture of sorrow and affection.

Ancestors of these cetaceans first entered these waters during the high sea levels of the middle Miocene period, roughly 11-15 million years ago. Since then they have developed echolocation and lost their eyesight, as they evolved in the murky waters of the Indus Basin. They even learned to swim on their side to efficiently navigate the shallow waters during the dry season. Now, however, this animal was helpless and reliant on us for rescue - all those evolutionary marvels proven futile against what we have done to our rivers – cutting, draining, and controlling them, imposing limitations on the movement of such a unique animal. I felt a sense of responsibility for the impact of my species on another.

In the ensuing years, I spent time with these dolphins during their transportation from canals to the main river, sometimes over rough or non-existent roads. On one occasion, I accompanied a dolphin that was constantly tossing and turning during the journey. In a spontaneous and emotional response, I gently placed my hand on its side and rubbed it slowly. I noticed how it helped calm the distressed dolphin. It was a natural and instinctive action, and I felt a reciprocal connection, at least on my part. This may sound unscientific and overly emotional to some, but I believe that conservation requires both emotion and compassion. To this day, we have rescued over 200 dolphins from the canals, but tragically, many others haven’t made it.

a global declaration was signed by 11 range state governments agreeing river dolphin conservation priorities

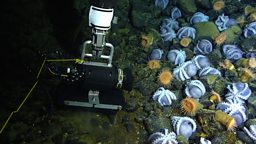

Since that first glimpse, I have dedicated myself to the conservation of the Indus dolphin and in that time the approach to conserving this species has rapidly evolved. It began with creating awareness through initiatives like establishing education centres and community outreach programmes to encourage reporting of stranded dolphins. Today, our work has become more innovative and technologically advanced. We're focused on understanding how dolphins navigate in a river that is disconnected and no longer free-flowing. The use of pingers (devices that emit sounds audible to dolphins) have proven successful in diverting them away from canal gates, and the use of tags have provided us vital information about their movement to improve our conservation efforts.

Since 2001, the Indus River dolphin population has made remarkable progress, increasing from 1,200 to 2,000 today, marking a significant conservation achievement. While we rightfully celebrate this success, it's vital to remember that the Indus dolphin's habitat is confined to an exceedingly small section of the river. Its range has declined by about 80%. Essentially, 98% of the population is concentrated in just 650 km of the Indus River. Improving water management is paramount to the species' survival.

As Pakistan's population surpasses 240 million, we face increasing challenges: ensuring food security, providing freshwater, and addressing the impacts of the climate crisis. This calls for a stronger emphasis on fostering coexistence between two species – humans and dolphins – who both share a critical need for freshwater. While the Indus dolphin considers it home, we often view it as a 'resource,' highlighting a fundamental difference in perspective.

There is cause for hope. In 2022, WWF - Pakistan and The Ministry of Climate Change hosted Asian range state governments and partners who agreed to work together to address the threats from fishing practices and recently in October 2023, a global declaration was signed by 11 range state governments agreeing river dolphin conservation priorities.

However much more needs to be done, if we are to save this elusive and unique animal and until we do, I will continue to devote my life to it.

Making Planet Earth III: Indus river dolphin

Cameraman Abdullah Khan recounts his experience in filming the Indus river dolphin rescue.