The Outrun: Amy Liptrot on connecting with nature

15 January 2016

is Amy Liptrot’s memoir about overcoming addiction while exploring the Orkney landscape. After a spell in rehab, she returns to her native islands and discovers that the place she once longed to escape offers her a cure; its wildness plays a crucial part in her recovery from alcoholism. SIMON RICHARDSON meets the author to discuss writing about nature, addiction and location aware astronomy apps.

There’s a moment toward the end of Amy Liptrot’s moving alcoholism memoir where she talks about a tendency in recovering addicts toward ‘cross-addiction’, where alcoholics transfer their addictive behaviour to something else.

“It’s commonly seen with food, exercise, shopping or gambling. For me, it’s Coca-Cola, smoking, relationships and the internet.”

This is a memoir about the healing power of nature.

This is a memoir about the healing power of nature. And as such you may feel you’ve heard the story before.

, published in 2012, saw the author take to North America’s to try to outwalk her dissolute life.

, Helen McDonald’s 2014 memoir, narrates her project of training a goshawk to hunt as a way of coming to terms with the sudden death of her father.

What makes Liptrot’s book different - unique perhaps - is the author’s obsession with the digital world.

“I don’t think I’d have gone to Papay in the first place if I didn’t know it had a broadband connection,” says Liptrot, explaining why she decided to move from her father’s Orkney farm to the even more remote island of .

Having a place of her own was a risk, “the perfect location to do some solitary drinking.” Fortunately that cross addiction proves very useful in keeping her out of trouble. The reader accompanies her tentative steps toward sobriety against the backdrop of this extraordinary landscape, in a book that is a kind of manifesto for using technology to embrace nature.

Liptrot is deeply curious about the space that surrounds her, walking and exploring the island for hours each day.

She uses an online app on her phone to track her routes. She’s seeking a fault line that runs through the island, but using the app she can also identify changes in her walking pace and in turn recognise that her walks are getting slower and more contemplative.

At night she’s dazzled by the , her viewings enabled by email alerts that relay time when the geomagnetic activity that causes the aurora peaks.

This juxtaposition of the online and natural worlds is at the heart of the book

“I got out of my bed and cycled out of town on reading those things online. There’s so many fantastic gadgets like location aware astronomy apps that I've used to bolster my meagre understanding of the stars, with these incredibly sophisticated location devices. And in Orkney they've been putting .”

This juxtaposition of the online and natural worlds is at the heart of the book and of Liptrot’s impulse to write.

Before The Outrun, appreciation of her work on the internet proved to her that the story she had to tell was interesting. “Not everyone grew up on a sheep farm and had to foster lambs. It allowed me to see my life through different eyes.” Twitter helped her hone a unique aesthetic, “You have to make a decision about what is your thing and I like those sometimes absurd juxtapositions. I often tweet about them.”

What does Liptrot say to those who see computers and the internet as a distraction from nature?

“It’s really easy when talking and writing about digital tech to fall into this trap of being critical, saying these devices are making us disconnected from the outdoors and each other. I was very keen to not do that, I wanted to show - which is very much what I believe - that there are so many ways in which technology can connect people to the natural world.”

As an approach, this openness about enabling technology is refreshing.

“Often it doesn’t fit with a certain aesthetic of natural materials, rugged and back to basics. Personally I like mixing things up. I write about building a dike while holding a digital camera, for some reason that juxtaposition really appeals to me. For me it throws up lots of unusual contrasts and unexpected and quite beautiful images… People shouldn’t pretend they’re using their compass when they’re using their Google Maps.”

Google Maps is another obsession. “Flying about on that site is something I use to relax. I scoured remote islands, and there’s a couple I kept going back to: , off the west coast of Orkney, and Fair Isle.”

As well as Orkney and London, this book explores an additional landscape, that of the internet itself. Of Sule Skerry she writes, “It seems the tides are strong around these parts of the internet, pushing me back here again and again.”

Talking to Liptrot you realise she regards terms like the natural world, nature writing and even technology as less useful than they appear. How do we define nature anyway? She points out that Orkney’s Neolithic , infused as it is with myth, was in fact the height of modern technology when it was built: “Those stones were fashioned to expand the capabilities of humans in some way, if that’s the definition of technology.”

As well as Orkney and London, this book explores an additional landscape, that of the internet itself

At the end of the book Liptrot observes “I never saw myself as, and resist becoming, the wholesome outdoors type.” Her upbringing has certainly shaped her relationship with nature. “I think because I’m a farmer’s daughter I come down more on the side of using nature, coexisting in it, I’m more practical.”

Liptrot’s has an ambiguous relationship with Orkney in The Outrun. Growing up she longed to leave and was deeply opposed to the way such landscapes are sold to tourists. She points out the modern aspects of this society: social media now helps island society cohere, often by sharing warnings about the weather or sightings of harbour porpoise.

Broadband might also be a force against depopulation: “The internet means it’s now more feasible for people to make a living. The smaller islands are really marginal communities. If the populations shrank any further the schools would close and they want to attract people to go and live there.”

The Outrun takes its name from a field on her father’s sheep farm, and in the final chapter, we learn this may be the subject of a compulsory purchase order to install to generate clean energy.

Liptrot is naturally conflicted, but brings a farmer’s daughter’s pragmatism to the debate. “It encapsulates my feelings about a reverence for the landscape and keeping it how it’s been and how it’s there to be used.”

In an increasingly crowded nature writing market, Liptrot’s unusual vantage point makes her one to watch. It will be fascinating to see what this startlingly original voice produces next.

Related Links

More from Books

-

![]()

Seven must-read novels by female authors.

-

![]()

Tolkien's own illustrations of his fantasy universe.

-

![]()

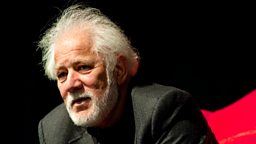

The author picks his three favourite works of science fiction.

-

![]()

Judge these books, and their genres, by their covers.

by Amy Liptrot was from Monday, 18 January 2016.

More from Â鶹ԼÅÄ Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms