Poetic justice: How the world caught up with Stevie Smith

10 February 2016

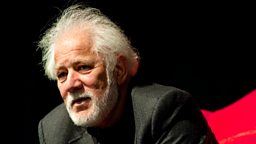

Eccentric; child-like; erudite; an odd-ball. The poet Stevie Smith was both lauded and patronised in her lifetime, often for the wrong reasons. BIDISHA considers one of Britain’s most distinctive poets and argues that it’s time to stop regarding Smith as a curiosity.

British poet became a national treasure in her own lifetime, but was it for all the wrong reasons?

Born in 1902, she is famous for the title poem of her 1957 collection . She also published seven other collections of poetry as well as three novels, beginning with her debut, , in 1936.

Despite her success, she is often represented as a quirky curiosity

Despite a career dip in the 1950s she was taken up by a new generation of readers in the 1960s and died, in 1971, celebrated and beloved.

Despite her success, she is often represented as a quirky curiosity rather than an object of intellectual admiration.

There is the lifelong spinsterhood; the suburban London home where she resided from childhood to death; the fact that she was brought up with her sister, mother and two aunts and lived on with one aunt until the end; her thirty years’ service as a company secretary, a job far beneath her talents; even her appearance, which made her look part-nun, part-child.

The irony, variety and erudition of her poetry is often overlooked in favour of patronising praise for its (and her) apparent simplicity.

Journalist Kate Kellaway, , described Smith as writing “like a grown-up child” and “looking like a dignified child”.

She mentions “the eccentric quality of her poems” while the article’s sub-header additionally describes Smith as an “eccentric poet.”

Smith’s physical appearance, work output and inner personality are conflated, objectified, amateur-psychoanalysed, then stereotyped, even by those who apparently appreciate her.

All of this makes Smith appear like some sort of idiot savant who never grew up, whose poetry had no thinking behind it and whose public image was un-self-aware.

All of this makes Smith appear like some sort of idiot savant who never grew up

Smith is ‘complimented’ for her innocence, transparency and an eccentricity which is not dangerous but somehow infantile.

As such she is the victim of the ultimate patronage: to be loved for having an amusing persona, without being esteemed for creating meaningful work; to be adored without being respected.

Yet there are signs that things are slowly changing and the 21st century is finally catching up with Stevie Smith.

Last year, a Hampstead Theatre revival of enjoyed a sold-out run with Zoë Wanamaker in the lead role.

Faber have also published a covetable edition of Smith’s , expertly edited and annotated by academic Will May.

On 15th February, featuring Smith’s drawings, performances from Zoë Wanamaker and contributions from academic Will May, critic and author Rachel Cooke, and historian Frances Spalding - author of the definitive Stevie Smith biography.

From the archives

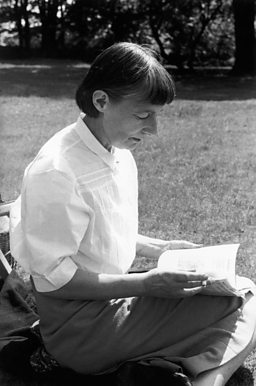

WH Auden and Stevie Smith in the pub in 1965

The poets sing and chat together in a pub in Edinburgh during the International Festival.

The poetry of Stevie Smith

Frances Spalding believes that even today, the literary establishment is slightly foxed by Smith’s poetry: “There’s a sense I get that critics are slightly uncomfortable with her work. She sets up a metre or diction and then suddenly goes off in a different direction. Is she being parodic or praising?”

She offers us a body of work that veers with unnerving regularity from baffling to acutely profound.”Zoë Wanamaker

The poem is a case in point.

It’s nowhere near the best of Smith’s output and is often given a face-value reading when taught in schools.

Will May warns against the simplistic conclusions readers might draw from it.

“That poem is used as a way to paint an all-too-easy portrait of someone who has all this turmoil underneath the surface," he says.

"Actually, Smith’s poetry tends to poke fun at people who are lost in their own work.”

For him, Smith has “an ability to gymnastically leap from tone to tone which is really unique in British poetry – [I love] the way poetry is allowed to behave and misbehave under her tutelage.”

Rachel Cooke relishes Smith’s ability to make poetry “deeply enjoyable” while keeping a unique complexity.

“No one else sounds like her,” she says. “The poems have this deceptive ease. They seem, at first, almost to be very witty, ironic nursery rhymes. But of course this is quite misleading. They are dark, and many of them come with this edge of malice. She twists the world: you recognise it, but it's disorientating, too.”

As Zoë Wanamaker concurs, Smith’s poetry is “disarming. She offers us a body of work that veers with unnerving regularity from baffling to acutely profound.”

Smith was a dedicated artist, a voracious reader and a consummate craftswoman.

She was a very clever woman – not a superficial cleverness but something rooted in a fundamental understanding of human natureFrances Spalding

Frances Spalding comments, “She was a very clever woman – not a superficial cleverness but something rooted in a fundamental understanding of human nature.

"At the University of Tulsa where her library went, there’s strong evidence of many drafts of her poems, with her reworking them even after they’d been published, in some instances. In her notebooks there’d be lists of books she’d read. She assembled a creative body of ideas and associations, full of literary allusions.”

For Will May, one of Smith’s great talents was for “bringing poetry to the stage. She understood this much better than other poets. The moment in her career when she found more fame was in the 1960s when people were being influenced by the Beat poets and coming around to poetry as performance."

He notes, "as a culture, the things which seemed bizarre or odd in her career, we’re now interested in.”

He is derisive about the image of Smith as a “Victorian aunt who doesn’t understand what she’s doing, stumbling into the world of genius or poetry.”

Smith lived through two world wars, the granting of female suffrage, rationing, the wartime rise in (and post-war repression of) women in the workplace, the sexual revolution and the Swinging Sixties – “a time of transformation in women’s lives and a flourishing of British creative culture,” as Zoë Wanamaker puts it to me.

Far from being unworldly, Will May describes Smith as a “shrewd operator” who could negotiate her own book deals “like a demon”.

Popular and sociable, Smith maintained a wide network of contacts through reviewing and broadcasting and knew exactly how to maintain a long career.

Despite this, the reputation for eccentricity has persisted.

As Frances Spalding tells me, “I think it’s a national habit on the part of the press to like women who succeed in the arts to be eccentric. It’s a way of explaining female success. The idea of having an extravagant personality is easy to grasp: there’s this fusing of the eccentric or the painfully dramatic.”

Yet much of Smith’s apparent eccentricity burns away under close inspection, when her choices look admirable, even radical.

The product of an all-female household after her father walked out on the family, Smith did not kowtow to anyone or anything: not to men, not to judgements against single or childless women, not to the demands of domestic life and not to changing fashions in poetry.

She understood that you have to be unique, you have to be idiosyncraticWill May

A confident, self-made woman with no family connections or literary Oxbridge chums (she didn’t go to university), she began her career by submitting her work to agents and editors.

Nor are her living arrangements so strange any more. Given the urban sprawl and the unaffordability of housing, living in suburbia with one’s parents is precisely what many adult Brits do these days.

A confession: I went to the same prep and junior school as Stevie Smith and, like her, live with my mother, up the road from Palmers Green, in the house I grew up in, at the age of 37.

“I don’t see hers as a tragic existence,” says Frances Spalding. “It certainly gave her a base from which to fling off.”

It could be said that like a true Englishman who believes that his home is his castle, Smith established the ideal base for herself: a stable home where she did exactly as she pleased, which was write poetry and pursue her career.

Will May agrees: “A writer needs space. Smith was quite canny and knowing about the stimulus she needed as an artist, to give herself the space to create.”

Even Smith’s apparent outsider status was a smart move to ensure longevity.

“She had a fear of being paired to other poets, living and dead,” says Will May.

“She understood that you have to be unique, you have to be idiosyncratic [to survive], so she had a horror of being absorbed into ‘trendy’ poetic movements. She knew the dangers of being part of a group: the group would fade in and out of interest and possibly be forgotten.”

Rachel Cooke says, “I think calling her an outsider, or an eccentric, is just another way of diminishing her.

Cooke concludes, "She was very conscious of how she came over; she knew just how to play people for maximum effect. She lived in the suburbs, it’s true, but she ran with a literary crowd. Why can’t we just call her ‘brilliant’ or ‘clever’ or ‘original’? Or all three.”

Poet in the City and Faber and Faber present at Kings Place, London, on 15 February at 7pm.

More from Books

-

![]()

Seven must-read novels by female authors.

-

![]()

Tolkien's own illustrations of his fantasy universe.

-

![]()

The author picks his three favourite works of science fiction.

-

![]()

Judge these books, and their genres, by their covers.

More from �鶹Լ�� Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms