Radical writing: Was Angela Carter ahead of her time?

1 August 2018

In a new documentary on �鶹Լ�� Two, Angela Carter: Of Wolves & Women, authors Margaret Atwood, Jeanette Winterson, Anne Enright and Salman Rushdie discuss the wild, inventive and often radical writing of the late author.

Angela Carter: Of Wolves & Women explores the extraordinary life and surreal imagination of the outspoken author of short stories and novels including The Magic Toyshop, Nights at the Circus and The Bloody Chamber. Although Carter was revered by many of her peers and her writing influenced successful authors such as Jeanette Winterson, Anne Enright and Salman Rushdie, she never won a literary prize and only entered the bestseller lists after her death in 1991. Where once she was ahead of her time, now her writing seems of the moment.

Carter twisted fairy tales

Most of today’s best-known fairy tales have been around for hundreds of years. In their early forms a lot of them were dark, violent stories: Bluebeard murdered multiple wives, Cinderella’s stepsisters sliced off sections off their feet to fit the glass slipper and pregnant Rapunzel was sent to give birth alone in the desert.

Over time they have become sanitised to suit the tastes of younger audiences or adapted by film companies into sweeter stories with a leading princess, a strong hero and a ‘happily-ever-after’ ending. Angela Carter’s approach was completely different.

Jeanette Winterson says: “What Angela Carter did with fairy tales was to take the stories that we all know like Bluebeard or Beauty and the Beast and turn them inside out. Take the components that were familiar and make them into something that gave women back the power.”

Carter put women at the centre of the stories and gave them agency over their fate. In The Bloody Chamber (based on the story of Bluebeard) the heroine’s mother shoots the murderous Marquis and they inherit his fortune. In The Erl-King, when the heroine learns the birds in the King’s cages used to be girls, she strangles him and sets the birds free.

Carter also embraced the erotic element of fairy tales, using them to explore female sexuality. In The Company of Wolves the heroine seduces the wolf that ate her grandmother before he can eat her.

Winterson says: “This isn’t about things that women and children do on a wet afternoon, this is about the deepest desires and appetites, the springs of human nature. These fairy tales have lasted so long because they’re talking to us at a psychological level.”

Salman Rushdie compares the monstrous men of her fairy tales to modern-day allegations against sexual predators: “Angela was very interested in ogres. So the monstrosity of men was always the subject for her. She knew very well what men were capable of.

“The title story of The Bloody Chamber is about Bluebeard, a real monstrous individual if ever there was one. Anyone who reads that now would see the application of that story to some of the monsters who have been recently outed.”

Beauties and beasts

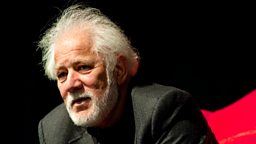

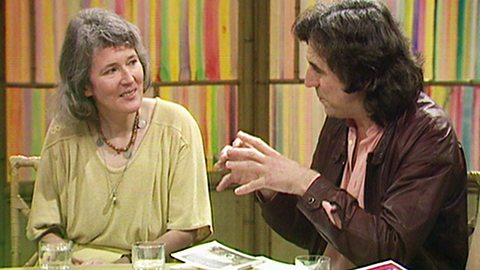

Angela Carter talks beauties and beasts with Terry Jones

Angela Carter discusses her work with former Python, Terry Jones, on Paperbacks, 1981.

"What Angela Carter did with fairy tales was to take the stories that we all know and turn them inside out. Make them into something that gave women back the power.”Jeanette Winterson

Carter rejected realism

Carter's characters were circus performers, puppet-masters and many-breasted mother goddesses. Her work is often described as ‘magical realism’, a popular genre today, but when Carter was writing in the 60s and 70s straight-up realism was seen as the pinnacle of fiction. Authors were writing novels that offered up a slice of life from everyday people.

Magical realism comes from the periphery, it comes from the colonies, it comes from women, it doesn’t come from people who own the world.Anne Enright

Margaret Atwood observes that Carter suffered for not writing realism: “She was writing a different kind of thing that people didn’t know what to call. And guess what, they still don’t know what to call it.

"She wasn’t a compromiser. So anyone who might have said to her, why don’t you write a novel about London slums, a la Zola, she would have just said no, that’s not what I do.

"In an age where you were supposed to be writing plainsong, she wrote baroque. She was very ornamented, she was very lush.”

For many readers Carter’s work was their first encounter outside realism. Anne Enright says: “I’m reared on Irish Naturalism, cups of tea and rashers in the pan, and there is Angela Carter, with flying women and glamour and eggs made from jewels.

“In 1980s magical realism comes from the periphery, it comes from the colonies, it comes from women, it doesn’t come from people who own the world. People who own the world and understand the world are men and they write big boring books in very boring sentences.”

Wise Children

Maureen Lipman reads from Wise Children

In Angela Carter's masterpiece, a 75 year old dancing girl refuses to go old gracefully.

Nights at the Circus

Kelly MacDonald reads from Nights at the Circus, the audacious story of a winged acrobat

Kelly MacDonald reads from Nights at the Circus, the audacious story of a winged acrobat.

Carter was a feminist

Women are at the centre of Carter's short stories and novels. Winterson says: “She was trying to lift women out of the many myths that they’d been placed in. Men have written fictions about women forever. And she was trying to get away from those particular male-authored fictions and say maybe we should write other kinds of stories about women?"

She was interested in a balance of scales. Not that women were more powerful than men.Margaret Atwood

These characters take active roles. Discussing The Bloody Chamber, Enright observes how in all those stories "women are freed either by going into the difficulty or by killing the big bad man. It’s about liberation, it’s a wonderful liberating book".

Her writing isn't anti-man, but anti-misogyny, Atwood says: “She was interested in a balance of scales. Not that women were more powerful than men, but in order to actually have anything that is not just dependency or sucking up or controlling, you have to have equality.”

Winterson says: “She was absolutely ahead of her time, and that’s why I think we’re so interested in her now. She’s coming into her time almost prophetically.”

-

![]()

Watch Angela Carter: Of Wolves & Women

The documentary is on �鶹Լ�� Two at 9pm on Saturday 4 August, and available on �鶹Լ�� iPlayer for 30 days thereafter.