BAME and shame: How non-white writers are shunned by the books industry

19 April 2016

Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) authors are consistently under-represented in British publishing, research has found. Despite the success of bestsellers by the likes of Zadie Smith and Monica Ali, many writers of colour are routinely ignored by the press, shunned by literary festivals and marginalised by an overwhelmingly white industry.

But a fightback is under way, with the formation of pressure groups, festivals and awards for non-white authors, and the arrival of a new publisher of African fiction. BIDISHA speaks to some of the key figures to discuss some possible solutions to the problem.

In February, a group of British writers launched the Jhalak Prize for best book by a writer of colour, in response to a long-growing frustration at the lack of recognition of such artists in the UK publishing, arts and cultural scene.

Last year’s World Book Night list featured no non-white authors, and each new wave of research into representation shows that such authors are rarely reviewed in the major papers, interviewed on radio or TV books programmes, featured as major literary critics or honoured on prize shortlists and literary festival rosters.

Additionally, in the UK, less than five per cent of work published is in translation. As a result of these and other exclusions, the We Need Diverse Books movement has started up with the aim of redressing the imbalance and challenging stereotyped, discriminatory, monocultural practices.

There are some sources of hope, such as the Man Booker International Prize, which from this year will be honouring a work of international literature in translation - with the prize money split equally between author and translator - and which this year features longlisted authors from 12 countries, writing in nine languages. But the general picture is bleak.

It’s strange, because over the last decade the success of authors including Monica Ali, Zadie Smith, Andrea Levy, Caryl Phillips, Bernardine Evaristo and others seemed to reflect a UK literary scene that was moving with the times.

Yet just last year journalist Danuta Kean published a thorough and damning report called Writing the Future: Black and Asian Writers and Publishers in the UK Marketplace.

As Kean tells me: “It showed that among novelists and publishers British-based BAME people are severely underrepresented, and that their experiences of publishing as writers and workers is poor: they feel marginalised, stereotyped and under-represented by an overwhelmingly white and middle class industry... there was very convincing evidence of unconscious bias operating to restrict access and career progression for BAME writers and publishers.”

Kean says: “I heard experiences of outright racism, like an author being asked, ‘Do black people read?’ Writers and publishing staff said they felt very isolated, especially when they are at launches and the only other BAME people are serving drinks.

I heard experiences of outright racism, like an author being asked, ‘Do black people read?’Danuta Kean

“In universities, reading lists and visiting lecturers are far more likely to be white, and again, the treatment of their stories as ‘exotic’ or other was a common experience, which is ludicrous in a multiracial society.”

I contacted many of my non-white author peers and asked about possible solutions to transform the industry and the wider culture.

Writer Chimene Suleyman commented that “there’s barely an industry that doesn’t suffer from structural racism. And the publishing world does come with historical attachments of white male elitism that in turn affects how quickly an industry wants to make moves to be more inclusive. Networks and cliques are a hard thing to crack. Half the time people don’t even realise they’re a part of them.”

She adds: “We’re expected to write about our brownness, blackness, our religions, our rapes. We can’t just tell the same boring stories about boring everyday things. What’s most concerning is when white people tell the stories of people of colour, or when men write these terrible female characters.”

Like Kean, Suleyman has noticed that “British [arts] festivals with a high focus on literature always astonish me with how white they are. I have read at festivals for five years and can count on both hands the writers of colour I see performing.

“People of colour are always voiceless and overlooked and when we raise these issues we’re told we’re over sensitive. England in particular is terrible at learning languages and looking elsewhere for culture unless it profits. It’s a hangover of the colony.”

Mend Mariwany, an editor at journalistic outlet Media Diversified and one of the organisers of London’s Bare Lit Festival, which launched this year to celebrate non-white UK literary talent, says that “while [publishers] taking on more authors of colour would address the symptoms, it wouldn't solve the root of this problem.

“People of colour are still missing at the level of leadership roles. And as long as leadership roles in the industry are occupied predominantly by white people, there is little incentive for authors of colour to pitch their ideas.”

The writer Irenosen Okojie, whose short story collection Speak Gigantular will be out this June, comments that “it’s encouraging to see publishers like Darf, who publish Arabic works in translation, and Jacaranda Books and Influx Press, who are actively looking to publish writers of colour.”

But when it comes to public appearances, she says: “When [non-white authors] are asked to appear a lot of the time it's on diversity panels. I'm not saying diversity panels aren't important but it's not the only thing to programme them for.

Okojie is a Prize Advocate for the SI Leeds Literary Prize for unpublished fiction by black and Asian women. Like all the authors I spoke to, she has some targeted advice for people working in publishing: “Look around you at your next series of meetings. If everybody around you is white, and all the authors you publish are white, consider doing something about that.

“Because if you're staying silent and deliberately keeping the blinkers on, you're condoning an unequal playing field and benefiting from your privilege by choice.”

She adds: “We need more black and Asian people starting publishing houses that operate as part of the industry. We need more people of colour within the infrastructure of publishing. We need editors to not just commission to their tastes, but really think about an interesting, eclectic list that's diverse in every sense, not just racially.”

When I ask Danuta Kean if non-white authors are expected to conform to a certain type in terms of the stories they tell, she jokes: “To get an idea of what it’s like, look at the cover of any book set in Africa. Regardless of which country forms the backdrop, I bet you a tenner that a banyan tree and a sunset will be on the cover.

“I also spoke to writers who were told that the idea of a football-loving Pakistani kid living in Brixton and listening to Mozart was ‘hard to believe’ so they had to change these things to reflect white stereotypes, As a result, black and Asian authors are turning to the US and the Indian subcontinent to get book deals for books that don’t pander to stereotypes.”

Western publishing is out of step with a real world that is very mixed, global and diverseBibi Bakare-Yusuf

As a counterpoint to these stereotypes, in April the UK literary scene will welcome a new publisher of fiction by African writers.

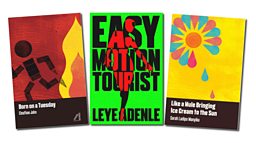

Cassava Republic Press, which has already been operating successfully in Nigeria for ten years, will be launching a range of new publications including contemporary Nigeria-set novel Born on a Tuesday by Elnathan John, Sarah Ladipo Manyika’s thoughtful literary novel Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun and Leye Adenle’s Lagos-set crime novel Easy Motion Tourist. I’m also very excited by Season of Crimson Blossoms by Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, the tale of an illicit affair between a 55-year-old widow and a 25-year-old street gang leader.

Cassava Republic Press founder Bibi Bakare-Yusuf is based in London and is working on the UK launch with Emma Shercliff, formerly of Macmillan and Hodder, currently in Nigeria.

Bakare-Yusuf comments: “Western publishing is out of step with a real world that is very mixed, global and diverse. Publishing is civilisation-building. Sometimes, builders of civilisation can forget to innovate, to experiment and to feel the pulse of what’s going on around them.

“If publishing is to continue to be relevant, civilisation-shaping, it must come to terms with the hybrid and multi-tongued world we live in. The world has so many cultural outputs competing for our attention and money, the only way to stay relevant is to mix up and be polyrhythmic.”

Related links

More books features

-

![]()

The poet turned author discusses her debut novel

-

![]()

A new gay narrative from the year's publishing sensation

-

![]()

Celebrating the 200th anniversary of Charlotte Brontë’s birth

More from Â鶹ԼÅÄ Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms