The wave: the world’s first viral image

-

![]()

Helen shares what she learned from In Our Time.

Whether it’s Kim Kardashian ugly-crying or a little girl standing in front of a burning building, viral pictures are a kind of social glue. Most people can understand why they’re funny or intriguing and they require no explanation. They might not be high-brow, but they’re instantly recognisable and have the ability to transcend language and culture.

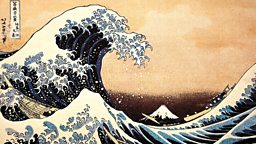

’s Great Wave is seen as the ultimate emblem of Japanese art and is the most reproduced image on the planet – there’s something comforting about seeing it. Whether I spot a reproduction of the woodcut in a café, a hotel, or someone’s downstairs loo, there are moments when it feels like seeing an old friend. It gives the effect of a fixed point in a spinning world. However, unlike the picture of Kim K crying, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, to give it its full name, was one of the first images to go viral.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

Angus Lockyer describes Katsushika Hokusai's Great Wave.

It was produced in the early 1830s as part of a series, Thirty Six Images of Mount Fuji, which actually contained 46 images (because apparently Hokusai can do whatever he damn well pleases).

The Great Wave is the most reproduced image in the worldAngus Lockyer

The Great Wave was not originally intended to furnish the bedroom walls of every humanities student, but the series was designed to show man’s smallness within nature. Simple, but geometrically complex, and with compassion and a sense of humour.

The Great Wave was exciting at the time because it made spectacular use of a new colour, Prussian blue. Beforehand, Japanese artists had to make do with indigo or a dayflower blue and nothing else, but now blue had stopped being boring, Hokusai could do something incredibly expressive.

While it was innovative, another image from the series – Red Fuji – was much more popular in 1800s Japan as it tapped into the spiritual reverence of Mount Fuji. I wonder what our choice of the Great Wave says about 20th- and 21st-century culture in the West?

The Great Wave is ubiquitous, but this didn’t happen during Hokusai’s lifetime.

A print was shown at the 1867 International Exposition in Paris (18 years after his death) and it had a huge impact. It influenced the work of every Impressionist – from Manet to Degas.

You can argue that without Hokusai’s Great Wave, modern art would have looked different. This strikes me as being quite similar to a viral image today, in that it became part of common culture – as soon as you refer to it or use it directly in your own work, people know what you’re talking about and what mood you’re trying to evoke.

Hokusai wasn’t a proto-Damien Hirst: money wasn’t important to him, but he did believe in spreading his message. He was so ambitious that he wanted to draw every single thing, from Chinese and Japanese divinities to landscapes to mundane homewares – everything.

Manga

He initially published ten volumes of drawings, each containing 60 pages covered with multiple images. These books were called his "Manga", which is a kind of prototype of modern manga – the meaning was slightly different in Hokusai’s time. Pity, because I would love to see a Hokusai image of a schoolgirl with cat’s ears and massive weepy eyes.

After a hiatus, ten more volumes of his Manga were commissioned, and this time he wanted them made with cheaper paper so that his ideas could be spread wider. Perhaps his early career producing celebrity prints – affordable and changing with current fashions – meant he was aware of the power of reaching a wide audience, and in doing so, foreshadowing the power of a viral image.

Improving with age

wanted to live until he was 110 because he kept improving with age.

Hokusai wanted to live until 110 because he kept improving with age

He embarked on his absurdly ambitious Manga project when he was in his 50s, created the Great Wave when he was around 70, and reached what the panellists deemed the top of his game when he was 80.

During his final decade Hokusai focused on the strange and imaginary, portraying mythical beasts and figures from Chinese legend and painting them on silk. Painting on silk means that once the brush touches the fabric that’s it – you can’t correct it. A sure sign of confidence and skill.

“Getting better with age” may be a cliché wheeled out by the middle-aged, but Hokusai transcended age by innovating and dedicating himself wholeheartedly to his lifetime’s work. He maintained that he didn’t produce anything of any merit before he turned 50.

It strikes me that Hokusai has also transcended the ages by making a picture that has been cheaply reproduced and displayed in homes and businesses around the world.