How Mary, Queen of Scots ruled against the odds

-

![]()

Helen shares what she learned from In Our Time.

developed a reputation for being a strong leader and she needed every scrap of that famous strength in order to keep a grip on her position.

She became Queen of Scotland when she was just six days old; she was sent away from her mother to France as a baby girl; she was a widow by the age of 18 in 1560; upon her return to Scotland she became a Catholic ruling a Protestant nation, and was – of course – a woman put in a seat normally occupied by men. (Men became a big problem for Mary, but more on that later).

Mary swept through her early years with an aplomb that I find inspiring

So, a pretty dodgy hand, as they go. A square peg in a round hole. But Mary swept through her early years with an aplomb that I find inspiring, if not a little terrifying.

When she was a young girl and living with her mother-in-law-to-be, Catherine Di Medici, she was asked why she did not bow to the Queen of France. Mary’s response: “Why do you not bow to the Queen of Scotland?”

I wondered why she was quite such a mainstay in listicles of the kickass-women-from-history variety, and her life so pored over by women today, and now I know. Mary has remained a celebrated figure in history for her forthright attitude and bravery.

Mary and her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I, were constantly compared as rulers, and seen to share a “sisterly” connection. While Elizabeth was seen as more intellectual, Mary was clever but personable and persuasive. And, the panel noted, viewed incorrectly as a “femme fatale”.

Reign, a 2016 TV show about her life has also been popular in the US, although I feel like I should emphasise that it is highly, highly fictionalised.

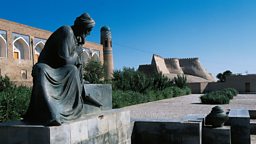

It struck me that what makes Mary particularly interesting now is that her life constantly throws up the question of what it means to be a good ruler. In this specific political age of shifting power, the election of Donald Trump and renewed interest in the idea of “sovereignty”, it’s fascinating to see how much Mary’s career as Queen involved “realpolitik” – accepting imperfections and being strategic rather than emotional or impulsive.

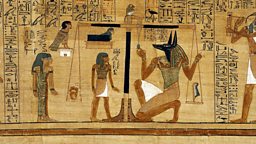

Despite being a devout Catholic, she was happy to rule a Protestant nation, for example, and came to accept that she could only worship in her way at Holyrood and nowhere else.

Mary's dealings with her second husband, the dashing Lord Darnley, are also a lesson in pragmatism. A single woman, it was suggested Mary ally herself with several unsuitable men (something everyone who has ever used Tinder will know about), but was eventually seduced by Darnley.

After they married, he quickly turned from charming suitor to drunken mess and went so far as to boycott the christening of their son, James, which left Mary reeling. Darnley was implicated in the murder of Mary’s much-trusted secretary Rizzio, and plotted with foreign powers behind her back.

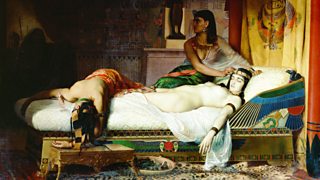

Why Mary, Queen of Scots' marriage to Lord Darnley ended in plots and murder

Melvyn Bragg hears why Mary’s second marriage turned quickly sour.

It’s thought that Mary had a plan to imprison her potentially dangerous husband in a castle, but someone else got to him first. His lodgings were blown up with dynamite and, curiously, his un-charred dead body was found nearby. Her patience with extremely trying men is an example to us all.

For it was not only Darnley who tried to control her, it was virtually every man who wanted power. Her marriage to the Earl of Bothwell came after he pledged to protect her – but only if she married him.

Mary's gender made her vulnerable, because if she did get married she was likely to fall prey to power-hungry, emotionally vacant men, and if she remained single she was a dynastic cul-de-sac. It was lose-lose.

Ultimately it was her “sister Queen”, Elizabeth, who kept Mary prisoner and signed her death warrant. However, the hostility of power-hungry men led to her entrapment and ultimate beheading. Mary was imprisoned because Queen Elizabeth's advisers Walsingham and Cecil falsified letters saying that she was plotting to kill Elizabeth, and her son James rejected her and refused to help free her. In this man’s world, she died friendless and alone.