9 things you may have missed about George Orwell’s 1984

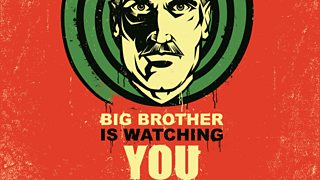

George Orwell’s 1984 is a masterful take-down of totalitarianism and one that has given us the concepts of Big Brother, the Thought Police, Room 101, groupthink, doublethink and many other terms that still resonate in political discourse.

On Radio 4’s In Our Time, Melvyn Bragg discusses this seminal novel with Prof David Dwan, Dr Lisa Mullen and Prof John Bowen. The panel uncover just how rich the work still is and highlight a number of things that readers may have missed when they read it.

1. Orwell’s time fighting in the Spanish Civil War was pivotal to 1984

George Orwell’s political thinking was dramatically shaped while fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Thanks to the influence of the Soviet Union, the Republican side spent a lot of time fighting each other as well as their common enemy, Franco’s Nationalists. Famously documented in Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, the civil war opened his eyes to how Stalinism had little to do with freedom and was more about control. This was pivotal to the creation of the totalitarian world of 1984, overseen by the figure of Big Brother, “the Party” and their dogma of Ingsoc (English Socialism), and the sinister Thought Police.

2. 1984 is a defence of human rights

The repression depicted in 1984 is, ultimately, “an impassioned defence of human rights”, says Prof David Dwan.

A self-proclaimed democratic socialist and a humanist, Orwell was among those calling for a charter on human rights after World War Two. This came into being in December 1948 (six months before 1984 was published) as the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which enshrined the right to a fair trial, to freedom of thought and to privacy – all things pointedly absent in Orwell’s novel.

3. 1984’s hero – Winston Smith – is deeply flawed

The main character, Winston Smith, is not a classic hero. He’s nearly 40, with varicose veins and false teeth, and is a troubled man, tormented by thoughts that he might have killed his mother. He also takes pleasure in the terror of refugees.

Smith is “deeply misogynistic”, Prof John Bowen observes, adding, “when he first sees Julia [his love interest and ally against Big Brother], he says he wants to flog her to death with a rubber truncheon”!

4. Julia is frivolous and Freudian

Julia is a hedonist who sleeps with various members of the Inner Party before she meets Winston, and someone who enjoys luxuries like lipstick and good coffee. These items and others are stolen from Party members, symbolic of Julia’s desire to break their rules, contrasting with Winston’s wish to attack them head on.

Of the Party’s control of recreational sex, Julia says to Winston: “All this marching up and down and cheering and waving flags is simply sex gone sour.” David Dwan says this attitude is Orwell’s way of representing a Freudian outlook on repression and underlines his belief that you need politics to make any real change and not just an understanding of where repression comes from.

5. The Proles are problematic

The Proles make up 85% of the population of Oceania and are kept benign on a diet of beer, football, lottery tickets and “prolefeed” – entertainment churned out by the Party.

Some feel that having the overwhelming part of the population as essentially free to do as they please is a plot hole but also that Orwell’s attitude to them was both sentimental and contemptuous.

Dr Lisa Mullen explains that Orwell ultimately uses the Proles to warn us off “marketisation”. “The Proles have chosen to be infantilised,” she says, “fed these lies and just go along with it. Orwell is trying to make a point about how, if we are just apathetic, we can end up losing our freedom.”

"Especially to us reading now, that seems like a massive hole in the book. It seems ridiculous."

An In Our Time panel on George Orwell's portrayal of Proles in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

6. Orwell’s vision of the future was at odds with Aldous Huxley and HG Wells

“Political predictions are usually wrong,” wrote Orwell, and so we have to consider 1984 less as a foretelling and more as a warning. That said, the book is also a repudiation of the predictions of others, such as Aldous Huxley’s advanced and hedonistic – albeit equally dystopian – society in A Brave New World and the shiny visions of the future presented by HG Wells. Rather than establish a utopia and then undermine it, Orwell chose to focus on how badly off people would be in his future.

7. Orwell’s impending death shaped the dystopian world of 1984

Orwell was diagnosed with tuberculosis two years before the publication of 1984 and the treatment he undertook for it almost certainly influenced his writing. He was confined to bed in a sanatorium and prohibited from sitting up, speaking, reading or writing. He was also subjected to injections into his lungs with huge needles and to constant X-rays. It was essentially a kind of torture, albeit for a medical outcome, and the sinister control it involved sparked Orwell’s imagination, setting the scene for Winston Smith’s ordeal in Room 101 at the end of the book.

8. Room 101 reflected psychiatric trends

Lobotomy and electroconvulsive therapy were well-known psychiatric treatments in the 1940s, and they also fed into the tortures of Room 101. Winston is taken there to be “made sane” and for Lisa Mullen this has echoes of contemporary psychological thought. “That was an idea that was current at the time, that criminality might just be down to bad wiring in the brain,” she says, “and if you sort of zapped it with enough electricity, you could make people good and you could change their personalities and their actions.”

9. Orwell was worried about “the end of history”

The mass proliferation of Stalinist propaganda in the Spanish Civil War caused Orwell to worry about objectivity and the survival of an impartial account of the conflict. “Orwell was a real empiricist who believed that all truth must be derived from what you can touch and feel, so it led to a certain kind of scepticism about history and the recording of history,” explains David Dwan.

In 1984, Orwell manifests his concerns in the re-writing of history by the Ministry of Truth, where Winston Smith works. The resonance of this is felt today with continuing anxiety over “fake news”.