Service Design methods have become more and more popular in recent years. In this blog Senior UX Designer Ferdinando De Meo discusses how the approach can help the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ to build better digital tools for its editors and journalists.

By applying lean UX practices in our design work, the UX&D team have collected many insights around pain points that users of our in-house online production systems can experience. However, when we compared our research activities a consistent pattern emerged: our users - mainly editors and journalists - are exposed to a large number and range of tools. But our research was giving too much importance to just a limited number, namely the ones managed by the product teams we were working with. This meant that on a regular basis, our research was not uncovering the real causes of our users’ problems and pain points.

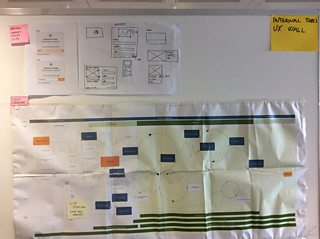

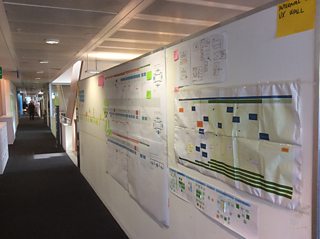

Experience Mapping and sketches on our wall

Picking a Service Design technique

With this in mind, at the beginning of this year I started to look at approaches that would allow us to both widen the focus of our research, and gain a view of the tools from the standpoint of the users. We had already applied several mapping techniques to internal tools - such as from Adaptive Path - but we had been focusing on specific tasks, e.g. uploading a video to used in an article. This time, with the aim of learning about totally unknown issues, we wanted to understand the full range of tools people were using and how they used them - not just thinking about predetermined sub-tasks with specific software. By looking at examples from other companies facing similar problems, and from personal experience, a Service Design approach seemed a good choice because of three main characteristics:

- The use of ethnography, as we needed to immerse ourselves in the world of Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ staff.

- Co-design techniques, to involve users in designing the solutions to their own problems, from their own perspective.

- Holistic thinking; the ability to see the tools as part of a wider ecosystem.

Among different service design tools, I realised that the would be best suited for our purpose, as we wanted to visualise the different phases of a service from the user perspective, and map those phases back to the software and the technical systems working behind the scenes. In order to use the technique, we needed to shift our approach and adopt a service perspective. We started by looking at our systems as part of one unified digital service, which was helping staff in putting their content online successfully. The visible part of the service were the tools, the invisible part were APIs and backend systems. Anything related to the tools, from training to tech assistance, would have been part of the service and its phases.

A process of change

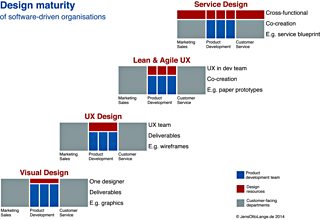

Although it may appear basic, this assumption changed the perception of our own work. We had to employ ethnographic observation and contextual enquiry more accurately than ever before, and Service Design pushed us to acquire new skills and sensibilities in the area of strategic design thinking practice. I was enthusiastic about this point, as it fitted with the way our design team could work with the product teams in a truly cross-functional fashion. This implied going beyond what we were already doing as UX designers, which consisted in applying Lean UX within pre-set agile teams, as exemplified by model for design teams in Software organisations. Familiarisation with Service Design was therefore the first step in this long process of change.

Models of progression of design teams in Software organisations (copyright: Jensottolange.de) from Touchpoint Vol. 6 No. 3 - December 2014

How we did it

After deciding on the technique, our next task was to select an area of the business to study, which would offer tangible information within the limited timeframe we had available. We focussed on shadowing journalists during their daily shifts in the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Birmingham Newsroom.

Our observations confirmed that teams were using a far wider set of digital tools. While our assumptions on how editors and journalists perceived our production systems were on the whole confirmed, we also saw that their working practices included not just digital software, but also other things such as 24/7 tech assistance, specific News software, broadcast management platforms, video-editing, emails and training. We were then able to identify potential pain-points that weren’t specific to any single tool, but rather arose through the interaction between non-digital elements (such as phone calls and print-outs) and software. This level of detail is something we wouldn’t have achieved solely through traditional interviews and testing focussed on usability issues and software usage.

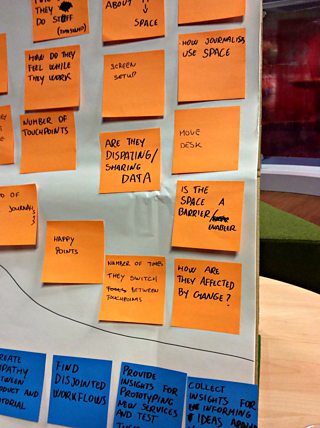

Before the observation: thinking about what we wanted to find out

Decoding together is key

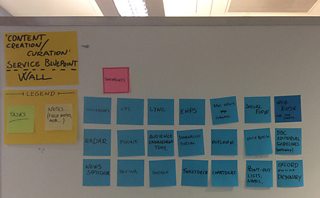

The next stage was to collate and present our data. We saved all of our findings digitally, making them accessible to everyone, then focussed our attention on the high number of tools and the ways in which teams interacted with them. We then went through a huge set of field notes, pictures and recordings, transcribing all the notes on post-its and print-outs on the wall in order to capture the full environment journalists work in.

Our wall during the decoding session

We were now able to transfer this information onto service blueprints, showing the different phases of a journalist’s ideal working shift. We shared these with the Product teams, in one-to-one meets with business analysts’s and product owners, feedback sessions with developers and designers, and via email to wider groups in order to initiate a conversation with our colleagues across the UK.

UX wall, with the Blueprints on the far end

Key findings and outcomes

Although the blueprints only covered a few profiles in their first iteration, they immediately resonated with team conversations, data from other streams of research and software trials, strategic plans, and first-hand knowledge in the team. They had the benefit of making the pain points of the users clear, but more importantly, they made manifest how tools were perceived as a unified service, especially to people new to the organisation.

In our daily design activity, the key outcomes of the blueprints have been:

1. Strengthening of cross-functional initiatives, such as our shared pattern library for increasing consistency across the tools

2. A clear business case for small design quick-wins - for instance adopting a common vocabulary (e.g. document status names) across the tools

3. A solid foundation of user knowledge, which could be used in interdisciplinary activities such as Design Sprints

In the longer term and in regard to organisational change and improvement, the outcomes were:

4. Developing the capability for UX teams to tackle complex issues and share actionable understanding in cross-discipline teams

5. The development of a circle of trust with the journalists and the editors, and a push for adopting a co-design approach more consistently, to include even more users in the design of features and priorities

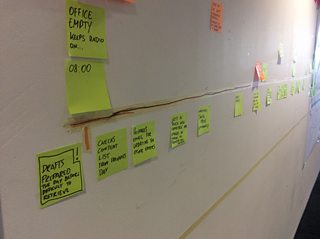

The touchpoints listed on our wall

It was encouraging when we discovered that people were spontaneously taking snapshots of some of the wall items, and including them in their documents and presentations. This was a sign we were working in the right direction for introducing and sharing a new approach within the organisation, and that there was an appetite to reflect together. By creating these blueprints, we've learnt some new skills and practice in co-design and ethnographic research. We've evolved our design-based approach to complex problems. This is extremely helpful for putting the user needs at the core of our everyday activity and influencing the long-term strategic thinking of our organisation.

The blueprints after some feedback sessions

What did not work

After some specific feedback around the first version of the blueprint, we realised that we were incorporating far too many details in the posters, and the ‘story’ we wanted to tell subsequently came across as too deep. The blueprints were difficult to read and empathise with, and this stopped people really engaging. As a result, we are currently working on a second version of the posters. We aim to improve their legibility and storytelling, so they are clearer and easier to take in, with more actionable insights focused on specific software issues that everyone in the product teams can familiarise with.

Although we engaged users and journalists, we have not yet managed to kick-off any long-term co-design activity. This is definitely part of our next objectives.

Next Steps

The idea is to go further with exploring and mapping areas of the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ in this way - involving more users and members of the teams in the discussion, and including co-creation - where people using the tools would be more actively involved in their definition. The months ahead are promising, as our department has put in place a new strategy for integrating all of the tools. Plus, the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ UX&D team have included Service Design in its objectives for this year, so it will be a good time to experiment and put these approaches to work within the organisation.