Unpicking five surprising ways fabric has shaped our world

24 May 2019

By covering our vulnerable bodies in textiles, human beings have conquered our planet and even reached the moon. But what we weave also has much to tell us about our own humanity, as experts and will explore at the Hay Festival.

Pioneering space seamstresses

In 1961 US president John F. Kennedy announced his ambition to land an astronaut on the moon before the decade was out. Among the huge challenges to overcome was manufacturing a spacesuit which could protect the human body from the dangers of space.

Playtex were a small firm whose expertise lay in latex moulding bras and girdles.Kassia St Clair

In The Golden Thread, Kassia St Clair describes the scale of the problem NASA faced.

She writes: "Space is the most alien environment in which a human being has survived... In space, temperatures fluctuate between -157°C in the shade and as high as 154° in a sunny spot... there is a great deal of ultraviolet radiation from the sun, which is harmful to our eyes and skin. There is no breathable air."

The company appointed to manufacture the spacesuit was, on the surface, an unusual choice.

St Clair reports: "[Playtex] were a small firm - no more than 50 employees in 1962 - whose expertise lay in latex moulding bras and girdles.... The making of what was to become known as the was much more akin to making girdles than anyone at the space agency would have cared to admit. Each suit was fashioned by hand on a sewing floor populated entirely by women - seamstresses, pattern-cutters and makers - using adapted Singer sewing machines, standard pattern templates and the skills both inherent and honed from years of making women's underwear."

Computing has a cloth origin story

Weaving is an ancient skill, one that can be traced back at least .

Hole-punched cards paved the way for another invention: computing.Kassia St Clair

St Clair says it was revolutionary: "These threads could then be used to create rope, nets and - when woven together on a loom, felted or knitted - textiles. Such technologies allowed our early ancestors to gather food more quickly, transport it over greater distances and more easily, and venture further afield to less temperate regions to seek out new habitats."

Innovations in production during the industrial revolution would even play a key role in propelling us into the information age.

St Clair explains: "In 1801 Joseph Marie Jacquard invented a loom that made it possible to mass-produce textiles with complex woven patterns, something that previously had taken a great deal of skill, time and expertise to produce. His '' was controlled, or programmed, by pieces of card marked with a series of holes that determined the pattern. Much later, these ingenious, hole-punched cards paved the way for another invention: computing. An American engineer repurposed the punched-card system to help record census data. His firm eventually became part of International Business Machines, latterly known as IBM."

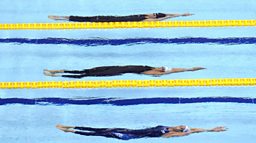

The cloth that makes you faster

Fabric has also played a significant role in the world of sport. The introduction of Speedo's full body swimsuit, the LZR Racer, in 2008 had a dramatic impact on elite-level swimming.

97 per cent of the golds won in the pool at the 2008 Olympics were taken by swimmers wearing LZR technologyKassia St Clair

St Clair writes: "Speedo had partnered with NASA to find the materials that best reduced drag... Less drag: faster swimmers. The fabric chosen was a lightweight, water-repellent and very smooth blend of polyamide and elastane, although it felt very odd against the skin: more like paper than cloth. The results spoke for themselves... 97 per cent of the golds won in the pool in Beijing [the 2008 Olympics] were taken by swimmers wearing LZR technology."

This swimwear revolution did not last long though, with the suits banned from competition use from 2010 onwards.

Changes in sports clothing are not always so unwelcome. When jogging became a mass participation sport in the 1970s, female runners were quite literally unsupported by manufacturers.

St Clair describes the issue: "Before 1977, women had their own, intimate ways of dealing with the problem. Some hacked regular bras with duct tape, others layered one bra atop another. [Then Lisa Lindahl, Polly Palmer Smith, and Hinda Schreiber] at the University of Vermont hit upon a more tailor-made solution: a pair of jock straps, sewn together. From this prototype the 'jockbra' - swiftly renamed the 'jogbra' for commercial reasons - was born."

Weaving a solemn reminder

In the 1980s the HIV epidemic killing thousands. In the United States social attitudes about the disease - it was dubbed a '' - slowed research efforts and stigmatised victims.

It played its part in raising funds for research, better sex education, preventative measures and effective drugs.Clare Hunter

Clare Hunter, author of Threads of Life, describes how gay rights activist Cleve Jones came up with the idea for a patchwork quilt that would honour those who had lost their lives to the disease.

She writes: "Its purpose was to create a fabric requiem that lamented the waste of so many lives through negligence and fear, on a scale and impact that would make its message inescapable and could campaign for more resources to stem the epidemic.

"Quilts were chosen as a deliberate ploy to evoke a wholesome association with home, family and comfort... On 11 October 1987, nearly 2,000 panels were laid out on the Mall of Washington DC, transforming it into an encrusted carpet... There are now 48,000 panels.

"The NAMES Project ensured that the public was witness to the scale of loss through a haunting and memorable spectacle. Public and governmental attitudes changed. And while the NAMES Memorial Quilt might not have been the trigger, it played its part in raising funds for research, better sex education, preventative measures and effective drugs."

Silent appeal for peace

In her book Hunter also tells the story of another marginalised group who used textiles to protest in the 1980s. was a movement started by retired school teacher Justine Merritt that was dedicated to ending the nuclear arms race.

The Ribbon didn’t just wrap around the Pentagon… It was 15 miles long.Clare Hunter

Hunter writes: "One night, in her sleep, she dreamed of an angel tied by a ribbon to the barrel of a gun.... She talked with friends and family about her idea of involving people in sewing peace panels that could be stitched together and wrapped around the Pentagon as a silent act of remembrance for the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and as an anti-war public protest.

"On 4 August 1985, 20,000 people arrived in Washington, DC to take part in the Ribbon... The Ribbon didn't just wrap around the Pentagon... It was 15 miles long. There were no speeches, no celebrity appearances, no razzmatazz... [It was] an alternative unification of human hope, a mass evocation of the preciousness of people, family and the earth.

"95 per cent of those who responded were women who would not describe themselves as political activists. But they found that the invitation to use their sewing skills for an issue they cared about struck a chord. Sewing was a medium they felt comfortable with. It was non-confrontational, personal, something they could do in the privacy of their own home and it required little expense.

"While the Ribbon attracted relatively little media attention, it left a lasting legacy. Justine Merritt conceived the Ribbon to encourage people to think more about how nuclear weapons affected them on a personal level, and to increase public engagement in the issue."

Hunter notes that although this relatively gentle form of political engagement seemed to go out of fashion in the 1990s, there are signs of a re-emergence in the 21st Century though groups like the .

Clare Hunter and Kassia St Clair will be talking to Rosie Goldsmith at the Hay Festival on . Threads of Life, by Clare Hunter, is published by Sceptre. The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History, by Kassia St Clair, is published by Hodder & Stoughton.