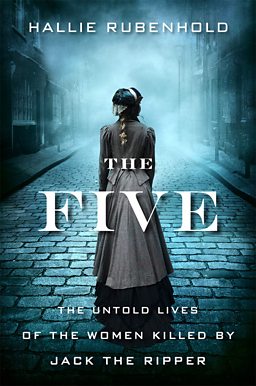

How the stories of Jack the Ripper’s victims are finally being told

24 May 2019

Polly, Annie, Elizabeth, Kate and Mary-Jane were at the centre of Britain’s most notorious unsolved crimes, but their stories have been eclipsed by the fascination with their murderer. In the first book dedicated to the women, which she introduces at Hay, Hallie Rubenhold shines a light on their lives.

In 1888, in London’s Whitechapel area, five women – Mary Ann 'Polly' Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine 'Kate' Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly – were murdered. Their killer was never identified. The person responsible, dubbed Jack the Ripper in the press, remains a subject of great fascination, with books, films and documentaries devoted to the crimes. Even today, there are still Ripperologists doggedly searching for clues as to the true identity of the killer.

The victims of Jack the Ripper and their lives have become entangled in a web of assumptions, rumour and unfounded speculation.Hallie Rubenhold

Yet very little attention has been paid to the identities of the five female victims. Hallie Rubenhold says: "The victims of Jack the Ripper and their lives have become entangled in a web of assumptions, rumour and unfounded speculation. They were formed at a time when women had no voice and few rights, and the poor were considered lazy and degenerate: to have been both these things was one of the worst possible combinations."

With her use of previously unseen archive material, Rubenhold is able to tell the true story of the women’s lives – and counter inaccuracies which have entered the popular imagination. For example, there is only evidence that two of the victims, Mary Jane Kelly and Elizabeth Stride, had ever worked as prostitutes. When the bodies were found in dark streets it was assumed by police that they had been lured to these places for sex. The coroner's inquest showed the murderer did not have sex with the victims and that they all died in reclining positions. There were no signs of a struggle and the killings appear to have taken place in silence.

Rubenhold says: "The police were so committed to their theories about the killer’s choice of victims that they failed to conclude the obvious: that the Ripper targeted women while they slept."

Real women with real lives

Many of these women had been married, had children, ran households and held down jobs. The Five explores how Victorian social factors left them sleeping rough in Whitechapel in 1888.

The five women had held jobs in domestic service, run coffee houses, worked in tin factories and sold . Once they had children women needed a man's income to support the family.

Rubenhold says: "No amount of women's labour in a factory, sweat shop or laundry, selling items in the street or doing piece-work from home would ever bring in an amount adequate to cover a family's needs and keep them from the workhouse."

By 1888 Polly, Annie, Elizabeth and Kate had all split from their husbands. Polly, who married at 18, left her comfortable house in the charity-run Peabody Building, along with her husband William Nichols and five children, with evidence pointing to William's affair with their neighbour Rosetta as the reason. After Polly left, Rosetta and William moved and began a life together with the children.

Annie left her husband John Chapman, along with her children and home on a country estate in Berkshire, after failed treatment for alcoholism. Kate suffered from domestic abuse for years before she split from her common law husband Thomas Conway, and Elizabeth and her husband John Stride parted ways after their business failed and their marriage produced no children.

Rubenhold says: "While separation among the working classes was not uncommon, it spelled the end of the woman’s respectable status among the ‘morally-minded’ of her community. Leaving the marital home rendered her unfit, immoral, a specimen of broken womanhood."

Not only were they regarded as a failure, after they had left a husband they couldn't remarry: any future relationship would be considered adulterous and any children of the unions illegitimate.

No amount of women's labour would ever bring in an amount adequate to cover a family's needs and keep them from the workhouse.Hallie Rubenhold

Born in Torslanda, near Gothenberg, Sweden, Elizabeth had become pregnant while working in domestic service. Rubenhold says that no household could operate efficiently without female labour but these women were given almost no opportunity to form relationships with the opposite sex outside their households and so liaisons within the households were common: "While the 19th century double-standard allowed men to walk away from such attachments, it often devastated the lives of the women."

While the 19th century double-standard allowed men to walk away from such attachments, it often devastated the lives of the womenHallie Rubenhold

This happened to Elizabeth. Pregnant, she lost her job and was reported to the police for ‘lecherous living’, as extramarital sex and illegitimate pregnancy were illegal.

She was placed on a police register as a prostitute. Unable to get respectable work, women would turn to the profession they had been accused of – as Elizabeth did until she was once again hired as a domestic servant and later moved with a family to London.

The least is known about Mary Jane. Rubenhold says that she worked in high-end prostitution in London’s West End and was potentially trafficked to Paris and managed to escape, moving to London's East End, where she sought to forge a new life.

Death and addiction

What is best known about the victims of Jack the Ripper is the violent nature of their deaths, but death was also ever-present in the lives of the five women, who lost parents, siblings, children and husbands to a variety of illnesses. Polly's mother and brother both died of tuberculosis when she was a teenager, Kate was orphaned at 14 and lost a daughter to malnutrition, while Annie lost four siblings in a matter of weeks to scarlet fever and typhoid, as well as her father to suicide and six of her eight children.

In a life filled with death and hardship, alcohol dependency was common and it played a part in the destruction of many relationships in the lives of the five women. Annie's father had been an alcoholic and while most of his children where teetotal, Annie was described by her sister as having a problem with drink from when she was 'very young'. She underwent a full year of treatment but when she turned back to drink she had to leave her husband and children. Back in London her family were members of the Temperance Movement, but unable to live with them Annie ended up living alone on her maintenance, and when her husband died she became homeless.

On the night of her death Polly had drunk her doss money (money required for a night's lodging) and was turned away from Wilmott lodging house. A similar situation happened with Annie at Donovan's lodging house, and Kate had been arrested for being intoxicated in the evening and was released from the cells, with no money for a bed, at 1am.

Polly, Annie, Elizabeth, Kate and Mary Jane lived hand-to-mouth existences. None except Mary Jane (who died in her bed) had permanent lodgings, none were employed or had family looking after them. Rubenhold says: "No one knew or cared what they did or where they went and for this reason, rather than a sexual motive, they would have appealed to a killer."

Hallie Rubenhold appears at the Hay Festival on . The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper is published by Doubleday.

Our fascination with the Ripper

The story of Jack the Ripper, most often depicted as a cloaked figure in a top hat lurking in the shadows of a smoggy London, is still ingrained into the city’s historical narrative some 131 years after the crimes. The story features in the London Dungeon, you can take Jack the Ripper tours and a dedicated museum opened in 2015.

It has also been the inspiration of numerous fictional accounts: from Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger in 1926, to the Golden Globe-winning 1988 mini-series Jack the Ripper starring Michael Caine as Chief Inspector Abberline and 2002’s From Hell (based on the Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell graphic novel), with Johnny Depp in the role of Abberline. There is even a pitting the murderer against the talents of Sherlock Holmes, which includes at least 19 novels and the films A Study in Terror (1965) and Murder by Decree (1979).

Women centre stage

-

![]()

The Women of Whitechapel

English National Opera follow the story of the five women in their world premiere Jack the Ripper: The Women of Whitechapel.

-

![]()

Look Up London have started a Feminist Jack the Ripper Tour focusing life for women in 19th century London.

Ongoing investigations

-

![]()

The Case Reopened

Actor Emilia Fox and criminologist Professor David Wilson look at the Ripper’s modus operandi using modern technology.