Improving accountability in Kenya

Jackie Christie

Senior Production Manager, Kenya and Somalia

Tagged with:

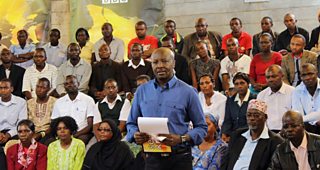

The editorial team of our TV and radio debate show Sema Kenya – which returns for its third season this Sunday – have to be some of the luckiest programme makers in Kenya.

A large chunk of any producer’s time is spent looking for relevant, up-to-date information that they can use to engage audiences and enrich programme content. Happily for our Sema Kenya producers they have access to our secret weapon: R&L – aka Â鶹ԼÅÄ Media Action’s Research and Learning department – who do a lot of this heavy lifting for them.

In addition to support from the R&L team in London, we have three R&L staff in our Nairobi office – Dr Angela Muriithi, Sam Otieno and Norbert Aluku – who provide the editorial team with insightful gold-dust, making Sema Kenya arguably the most rigorously researched programme in Kenya today.Â

Over the last two years the team has conducted focus groups, rapid audience feedback sessions, national surveys and more. They’ve sifted through a blizzard of figures, mountains of qualitative data and performed weird and mysterious tasks such as ‘regression analysis’. (I’m told it’s not painful.)

And it’s all to make sure that Sema Kenya isn’t just a great programme that appeals to its audiences, but one that also achieves its development objectives: supporting accountability in Kenya by providing people with a platform for constructive, audience-driven debate.

Media and Kenya’s elections

The R&L team’s in-depth analysis is evident in by Dr Angela Muriithi and her colleague Georgina Page, which sets out to explore the role Sema Kenya played during the Kenyan 2013 general election.

As with all of the R&L team’s outputs, the paper aims to not only inform our production but also support others in our field. It’s so others can use the data too and only last week, Angela also presented the research at a which brought together more than 200 electoral commissioners, judges and senior state officials from across the world to discuss and share knowledge about electoral support.

But to understand exactly why this research is important and relevant now, we have to go back to Kenya in December 2007.

The general election that Christmas was exciting. It was my first Kenyan election, and just as in the UK, I was glued to the media watching and listening to results and the endless analysis throughout the day of the vote.

What struck me was that unlike voters in many European countries, the majority of Kenyans still clearly sufficiently valued participation in the democratic process to stand for hours in the hot sun, queuing to cast their vote.

Watching lines of patient voters here is an awe-inspiring sight. It illustrates a faith in the democratic process that I only vaguely experienced as a UK voter at my local community hall.

Sadly for Kenya, the promise of that ballot was all too quickly extinguished.

Within hours of the voting booths closing and the winner of the presidential race being announced, a wave of violence was unleashed which saw over 1000 people murdered and half a million displaced.

Finger-pointing swiftly followed, with the media taking a large portion of the blame.

Everything from mis-reporting to hate-speech was said to have stoked the flames of the mayhem that followed the election.

It’s little wonder then that the 2013 election and the media’s role was so closely scrutinised.

‘Negotiating difference’

In the analysis of the media’s role during the 2007 election, a new term entered the vocabulary: ‘negative ethnicity’. In a country made up of more than 50 tribal groups one might expect this to be inevitable.

However this does not explain the previous decades of relatively peaceful co-existence.

What this briefing paper has shown however is that Sema Kenya is helping to encourage dialogue between disparate groups by highlighting commonalities rather than differences.

In a huge and geographically diverse country like Kenya, providing a platform to ‘negotiate difference’ as the researchers call it, can clearly provide some much needed social glue.

The paper doesn’t neglect to point out however that the media’s behaviour during the 2013 election was to some extent cowed.

So chastened was it by the accusations laid at its door after 2007’s awful events, it was said to have overcompensated in its desire to maintain peace. This could explain why the research showed Kenyans felt the media coverage during the election lacked depth.

Empowering effect

For me the most powerful role a programme like Sema Kenya can play in this context is to offer a mechanism for people to question those they elected.

The accountability agenda for Sema Kenya is its driving force and one the programme makers work hard to maintain.

This new research shows that the programme is helping to encourage Kenyans to expect more than just empty promises from their leaders. It is also empowering Kenyans themselves.

An audience member at one of the recordings explained why it is important programmes like Sema Kenya remain in the Kenyan media landscape: “There is someone like me and you… when you watch, it kind of inspires you to want to be like this other person. It makes you ask yourself, if this person is participating, why am I not participating? Because most of the time people don’t participate because they feel the political process is for the elites.”

Before, during and after elections, the need to stimulate debate, discussion and dialogue between Kenyans and their leaders remains as necessary as ever.

The third series of Sema Kenya (Kenya Speaks) starts on KBC1 and Â鶹ԼÅÄ Swahili on Sunday 27 April 2014.

Related links

Follow Â鶹ԼÅÄ Media Action on and