Interview with Director Mark Kidel on making the documentary

Mark Kidel is a documentary filmmaker and writer who lives in Bristol, England. His award-winning films include portraits of Boy George, Ravi Shankar, Rod Stewart, Bill Viola, Iannis Xenakis, pianists Alfred Brendel and Leon Fleisher, Derek Jarman, Balthus, Tricky, Robert Wyatt and American theatre and opera director Peter Sellars. A pioneer of the "rockumentary", Kidel was also the first rock critic of the New Statesman and contributed pieces on rock, soul, and world music, to The Observer, The Sunday Times, and The Guardian.

When did you first come across Elvis?

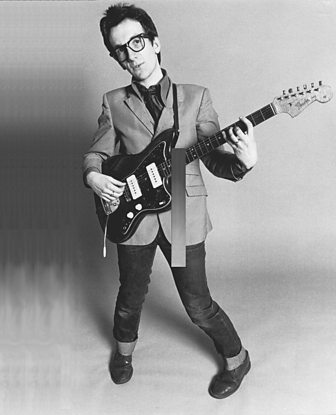

Back in 1977, I was the first person to write a regular rock column for the New Statesman. A friend in the music business, Paul Conroy, who was then working as general administrator with the maverick label Stiff Records - and went on to sign the Spice Girls to EMI - sent me the first single by an unknown with the unlikely name of “Elvis Costello”. You have to remember that the “Pelvis” from Memphis was still alive and there was something almost sacrilegious about adopting his name. The alias Declan McManus had chosen reflected a remarkable self-confidence, something which Elvis Costello has displayed throughout his life.

What was the single?

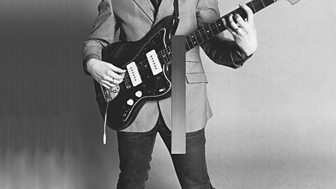

It was “Less Than Zero” a strange song with references to the fascist leader Oswald Mosley. What struck me most was the mixture of strength and vulnerability in the voice, and the incredible originality, both in terms of melody and in terms of lyrics. This was clearly someone to watch out for and I devoted the whole of my column to this new voice. We then met, as I’d proposed a profile to the Observer Colour Supplement. I went to his second gig ever with the Attractions – the supercharged band that was put together to take his first album out on the road, an album that’d been recorded with the American country rockers Clover - at the Woods Centre in Plymouth, which was almost empty; they gave a blistering performance. Punk was around and Elvis had something of that ‘taking-no-prisoners’ energy, but it was also as if he were deftly channeling decades of pop and rock history, a kind of deranged yet knowing Buddy Holly. He was mesmerizing. Not a great guitarist, but the Attractions - tight as could be - made up for that.

What’s so special about Elvis Costello?

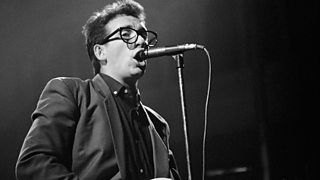

Well, first of all I think that, as a songwriter, he’s in a class with Paul Simon, Lennon-McCartney, and Bob Dylan. He’s not just a great popular musician, in tune with his times, but he has an uncanny way with words. He may be more of a poet than any of them – except perhaps Dylan – as many of his lyrics are so allusive as to be impenetrable. They are obscure and yet they grab your attention, make you think. He loves to play with clichés, draw out hidden meanings, and he does it with acerbic wit. He’s rarely easy listening and that may be one of the reasons, many people find him ‘difficult’. He’s also someone who has refused to be pinned down by style, and he has a phenomenal knowledge of music – rock, American musicals, jazz, soul, country, folk – I’m always astounded by what he has listened. Of course that all started with his dad doing covers of hits for the Joe Loss Orchestra, as Elvis recalls in the documentary: his dad would bring back white label singles to learn new songs by the Beatles, Trini Lopez or the Stones, and young Declan would get to hear them all. Many people find his cleverness off-putting. He is an encyclopedia and not just of the completist or trainspotting variety. He loves music. He is the ultimate fan!

How did the film come about?

Once again, my old friend Paul Conroy was involved: he now puts together box sets for Universal, Elvis’s label, and he suggested that I might do a film with Elvis. It didn’t look good and his manager told me that Elvis had no interest whatsoever in doing a documentary. Even so, Universal flew me to Vancouver, where Elvis was then living, and we had breakfast together – mad, but true. I imagined we’d spend an hour or together, but the meal lasted over three hours. We talked about music – what else? It helped that I’m, along with many of my generation, someone who listens to opera as well as gospel and blues, Charlie Parker and bebop as well as Tamla Motown. So we meandered around, discussing the finer points of the jazz drumming of Max Roach and Roy Haynes, the underrated qualities of southern soul singers James Carr and O.V Wright, and the best interpretations of Schubert’s song cycle “Winterreise”. What won him over in the end, was that he was intrigued, I think, by the two films I gave him as calling cards – portraits of the classical piano giant Alfred Brendel and the rock maverick Robert Wyatt. He and Diana Krall (his wife) watched and liked them very much. Alfred is in the new documentary – an extract of an encore I shot at his very last British recital in Dorset – as is Robert, singing his version of Elvis’s great political anthem “Shipbuilding”.

What was Elvis Costello like to work with?

He was amazingly generous. At the start, we had to postpone filming as his dad was very ill in hospital. I feared the whole thing might collapse. His father died not long after, and I expected Elvis would naturally withdraw from public engagements, and certainly not want to expose himself to documentary cameras. I don’t think one can underestimate the importance of his father on Elvis and the film hopefully makes this very clear – that closeness actually just got more intense. Elvis was sifting through family scrapbooks, and coming up with loads of amazing stuff that he wanted to share in the film. He was also thinking hard about how much his father’s experience had shaped him: not least the fact that his dad had given up the music he loved – bebop – because it didn’t pay the bills, he now had a child (Elvis), and thrown himself into more lucrative singing with a dance band. You can see that mirrored in Elvis’s own refusal to be commercial – to repeat himself if an album is a hit and sells well. He has tended to do the opposite, confounding his fans with sharp turns in his career. I find that pretty impressive. Others think he’s just inconsistent and tries his hand at too many different things.

What were some of the great moments in the filming?

Making a film about someone like Elvis Costello is a real treat. I just watched the film I made ten or so years ago about Ravi Shankar and I realize that I am amazingly privileged to be able to make these films about such incredible creative people. Elvis is the same – there is no one quite like him, in terms of range – you know stuff with a string quartet, or co-writing with Burt Bacharach. So although the mechanics of making these films are never easy-going, the reward lies in working with great people and great music. I never thought I’d stand in Paul McCartney’s studio, listening with him to demos he’d written and recorded with Elvis several decades ago. We’d just filmed the interview, and Paul suggested I might like to use some of the demos in the film: none of them had ever been released or heard in public, just rough versions with vocals and guitars and a bit of piano, recorded the very day they were written. So he got one of his engineers to pull the files out, and there we were, listening to the stuff, both of us finding the energy and rhythm of the songs irresistible, smiling away and moving to the music side-by-side. He was visibly moved – there’s something about the rawness of those recordings that you rarely get with stuff recorded more seriously.

It was also great to meet T-Bone Burnett, someone I had admired from afar, and whose production work, notably for Robert Plant and Alison Krauss, I had really liked. He spoke so eloquently about his work with Elvis – with a marvelous sense of story-telling and timing. And all of that in Nashville, that was my first visit to the country capital: a much smaller place than I had imagined, where all the music people know each other, and you can sense that this has something to do with the lasting quality of the music that is made there.

And last but not least, the pleasure of meeting Allen Toussaint, with whom Elvis has worked several times. One of my heroes too – all those great Lee Dorsey hits in the sixties and much more. What a gentle guy! There’s a nobility in the way he talks about music, and a generosity when he speaks of Elvis that is very rare. We were only with him for an hour or so, but it is not a time I would easily forget. All those qualities are there, somehow, in his music. And that Elvis should want so much to work with him, and promote his music all over the world, says a lot about Costello’s own generosity, and his love of music.

-

![]()

Find out more about Elvis on �鶹Լ�� Music

-

![]()

Jan Younghusband, Head of Commissioning, Music and Events TV explains why.