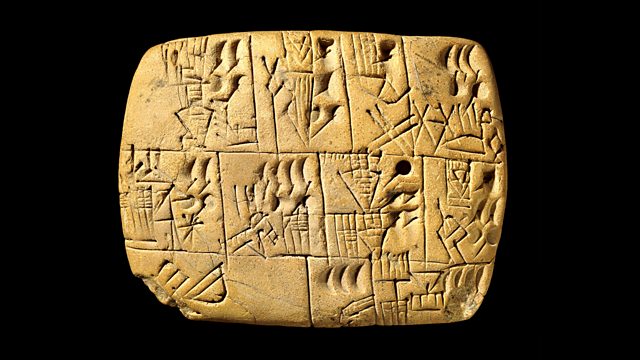

Early Writing Tablet

A History of the World celebrates the arrival of writing into our history with a 5,000-year-old Mesopotamian clay tablet that deals not in poetry but in describing the local beer!

This week's programmes in the history of the world looks at the growing sophistication of humans around the globe, between 5000 and 2000 BC. Mesopotamia had created the royal city of Ur, the Indus valley boasted the city of Harappa and the great early civilisation of Egypt was beginning to spread along the Nile. New trade links were being forged and new forms of leadership and power were created. And, to cope with the increasing sophistication of trade and commerce, humans had invented writing.

In today's programme, Neil MacGregor describes a small clay tablet that was made in Mesopotamia about 5000 years ago and is covered with sums and writing about local beer rationing. The philosopher John Searle describes what the invention of writing does for the human mind and Britain's top civil servant, Gus O'Donnell, considers the tablet as an example of possibly the earliest bureaucracy

Last on

More episodes

Next

You are at the last episode

![]()

Discover more programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects about communication

About this object

Location: Iraq

Culture: Ancient Middle East

Period: About 3100 - 3000 BC

Material: Ceramic

Μύ

This piece of clay contains some of the earliest writing in the world. It's called 'cuneiform,' which means wedge-shaped. This tablet is a record of the daily beer rations for workers. Beer here is represented by an upright jar with a pointed base. The symbol for rations is a human head eating from a porridge bowl. The round and semicircular impressions represent the measurements. All the signs were produced by a cut reed.

When did writing develop?

The oldest known example of writing comes from Mesopotamia and dates to about 3300 BC. In time different-looking writing appeared in the river valleys of Egypt, the Indus Valley, China and Central America. We cannot yet be certain whether writing spread from Mesopotamia, or developed independently in these civilisations. As Mesopotamian society became more complex, writing allowed administrators to keep an account of who had been paid and what had been traded. The earliest cuneiform tablets are almost all records of accountancy.

Did you know?

- Ancient Mesopotamian maths was based on 60, which is why we have 60 seconds in a minute and 60 minutes in an hour.

The beginnings of a state

By Gus O’Donnell, Cabinet Secretary and Head of the British Civil Service

Μύ

This tablet is amazing. For me it’s a first sign of writing but it also tells you about the growth of the early beginnings of a state. You’ve got a civil service here, starting to come into place in order to record what is going on. Here is very clearly the state paying some workers for some work that’s been done. They need to keep a track of the public finances, they need to know how much they have paid the workers and it needs to be fair.

What’s amazing for me is that this is a society where the economy is in its first stages, there is no currency, no money. So how do they get around that? Well, the symbols tell us that they have used beer - beer glorious beer, I think that is absolutely tremendous; there is no liquidity crisis here, they are coming up with a different way of getting around the problem of the absence of a currency and at the same time sorting out how to have a functioning state. As this society develops you can see that this will become more and more important and the ability to keep track, to write things down, which is a crucial element of the modern state – that we know how much money we are spending and we know what we are getting for it – that is starting to emerge.

This tablet for me is the very equivalent of the cabinet secretary’s notebook, it’s that important.

Oldest language speaks of…beer

By Irving Finkel, Curator, British Museum

Μύ

A tablet with beer allocations – a good 5,000 years old – pinned up in a glass case like a butterfly for all to see. What can be interesting in that beyond the fact, obvious enough when you think about it, that hard-working individuals throughout history have always wanted their glass of beer?

Well, this most ancient document – like all its neighbours in the British Museum – deserves more than a quick glance.

It is written in cuneiform, the oldest known writing in the world, a non-alphabetic kind of writing that grew out of a simple system of pictographs into a flexible medium with which the Sumerian (unrelated to anything) and Babylonian (related to modern Hebrew and Arabic) languages could alike be recorded.

And all this began before 3,000 BC. From the outset the writing was done on clay, a most fortunate decision because tablets survive in the ground for millennia even when unbaked. A cascading waterfall of inscriptions has gradually become available, accounting for more than 3,000 years of history. Only a handful was originally intended to survive long-term; the remainder are more or less ephemeral documents that cover many aspects of life in Mesopotamia, state and private – from beer rations to heroic literature with every kind of document in between.

In the British Museum we have a treasure-store of such writings, about 130,000 of them. They represent a marvellous challenge. One hard-to-learn script, two hard-to-learn languages and the whole of ancient Mesopotamia is at your feet.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Fri 5 Feb 2010 09:45Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4 FM

- Fri 5 Feb 2010 19:45Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

- Sat 6 Feb 2010 00:30Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

- Fri 8 May 2020 13:45Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

- Fri 8 May 2020 21:45Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Communication—A History of the World in 100 Objects

A History of the World in 100 Objects - objects related to communication.

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects