Episode Transcript – Episode 15 - Early Writing Tablet

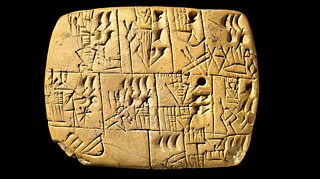

Early writing tablet (made around 5,000 years ago). Clay, found in southern Iraq

Can you imagine a world without writing? Without any writing at all?

No forms to fill in of course, no tax returns, but also no literature, no science, no 'history'. It is almost beyond imagining, because our modern life, and above all our modern government, is based almost entirely on writing. Of all mankind's great advances, the development of writing is surely the giant: I think you can say that it's had more impact on the evolution of human society than any other invention. But when and where did it begin - and how? This programme's object is a piece of clay, made just over five thousand years ago in a Mesopotamian city. It's one of the earliest examples of writing that we know; it's about beer and the birth of bureaucracy.

"For me, it's a first sign of writing, but it also tells you about the growth of the early beginnings of a state." (Gus O'Donnell)

"It's essential for the creation of what we think of as human civilisation. It has a creative capacity that may not even have been intended." (John Searle)

When, around five thousand years ago, the earliest cities and states grew up in the world's fertile river valleys, one of the challenges for leaders was how to govern these new societies. How do you control not just a couple of hundred villagers, as it had been, but tens of thousands of new city dwellers? Nearly all these new rulers discovered that, as well as using military force and official ideology, if you want to control populations on this scale you need to write things down.

We've already talked about a sandal label of an Egyptian pharaoh that had early writing on it, in hieroglyphs. Now we're back with the Mesopotamians who made the standard of Ur, and we're looking at one of the earliest examples of writing from there, in what is now southern Iraq. It's on a little clay tablet, about four inches by three, made about five thousand years ago, and it's almost exactly the same shape as the mouse that controls your computer as you move it around your desk.

We tend to think of writing as being about poetry or fiction or history, but early literature in that sense was in fact oral - learnt by heart and recited or sung. You wrote down what you couldn't learn by heart, what you couldn't turn into verse, so that pretty well everywhere writing seems to have been about record-keeping, bean-counting, or, as in the case of this little tablet, beer-counting. Beer was the staple drink in Mesopotamia and was issued as rations to workers. Money, laws, trade, employment; this is the stuff of early writing, and it's writing like the writing on this little tablet that changes the nature of state control and state power - bureaucratic and economic. Only later does writing move from rations to emotions; the accountants get there before the poets. It's all thoroughly bureaucratic stuff, and so we asked Gus O'Donnell, the head of the British civil service, to talk to us about why he thinks the first writing in Mesopotamia was about organising the state:

"This tablet is amazing. You've got a civil service here, starting to come into place in order to record what's going on. Here is very clearly the state paying some workers for some work that's been done, they need to keep a track of the public finances, they need to know how much they've paid: it needs to be fair."

So, by 3000 BC, the people who had to manage the various city-states of Mesopotamia were discovering how to use written records for all kinds of day-to-day administration, keeping large temples running or tracking the movement and storage of goods. Most of the early clay tablets in our collection, like this one, come from the city of Uruk, roughly halfway between modern Baghdad and Basra. Uruk was just one of the large rich city-states of Mesopotamia that had grown too big and too complex for anyone to be able to run them just by word of mouth. Gus O'Donnell again:

"What's amazing for me is of course this is a society where the economy is in its first stages, there is no money, there is no currency. So how do they get around that? Well, the symbols tell us that they've used beer - beer glorious beer. I think that's absolutely tremendous; no liquidity crisis here, they are coming up with a different way of getting around the problem of the absence of a currency and, at the same time, sorting out how to have a functioning state. And, as this society develops, you can see that this will become more and more important. And the ability to keep track, to write things down, which is a crucial element of the modern state - that we know how much money we're spending, and we know what we are getting for it - that is starting to emerge. And this tablet for me is the first ever equivalent of the cabinet secretary's notebook - it's that important."

Writing confers such power, that it inevitably became the subject of magic and myth. A later Mesopotamian epic poem gives us one version of how it all began:

"Because the messenger's mouth was heavy and he couldn't repeat the message, the Lord of Kullab patted some clay and put words on it, like a tablet. Until then, there had been no putting words on clay."

Clay may not seem to us the ideal medium for writing, but the clay from the banks of the Euphrates and the Tigris proved to be unbeatable for all kinds of purposes, from building cities to making pots, or even, as with our tablet, for giving a quick and easy surface to write on. From the historians' point of view, clay has one huge advantage: it lasts. Unlike the bamboo used by the Chinese to write on, which rots quickly, and unlike paper, which is so easily destroyed, sun-baked clay will survive in the ground for thousands of years - and we're still learning from those clay tablets. In the British Museum, we look after about 130,000 written tablets from Mesopotamia, and scholars from all over the world come to study the collection.

While experts are still working hard on the history of the script some points are already very clear, and many of them are visible in this oblong of baked clay. You can see very clearly how a reed stylus has pressed the marks into the soft clay, which has then been baked hard so that it is now a handsome orange. If you tap it - you can hear that this tablet is very tough indeed, that's why it has survived; but one of our problems in the British Museum is that we often have to re-bake the clay, in order to preserve the information inscribed on them - indeed we have a separate kiln for re-cooking Mesopotamian tablets.

Our little beer-rationing tablet is divided into three rows of four boxes each, and in each box the signs - typically for this date - are read from top to bottom, moving right to left - before you move onto the next box. The signs are pictographs, drawings of items which stand just for that item or something closely related to it. So the symbol for beer is an upright jar with a pointed base - a picture of the vessel that was actually used to store the beer rations. The word for 'ration' itself is conveyed graphically by a human head, juxtaposed with a porridge bowl, from which it appears to be drinking, and the signs in each one of the boxes are accompanied by circular and semi-circular marks - which represent the rationing numbers.

You could say that this isn't writing in the strict sense, it's more a kind of mnemonic, a repertoire of signs that can be used to carry quite complex messages. The crucial breakthrough to real writing came when it was first understood that a graphic symbol, like the one for beer on our tablet, could be used to mean not just the 'thing' it showed, but what the word for the 'thing' sounded like. At this point writing became phonetic, and then all kinds of new communication became possible.

When writing in this full sense was taking off, life as a pioneer scribe must have been very exciting. The creation of new sound signs was probably quite a fast-moving process, and as they developed, the signs would have had to be listed - the earliest dictionaries if you like - beginning an intellectual process of categorising things and relationships, that has never stopped since. Our little beer-ration tablet leads directly, and swiftly, to a completely different way of thinking about ourselves and about the world that surrounds us.

But what does it do to the human mind when writing becomes part of culture? We asked John Searle, Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley:

"I think you don't understand the full import of the revolution brought by writing if you think of it just as preserving information into the future. There are two areas where writing makes an absolutely decisive difference to the whole history of the human species. One area is complex thought. There's a limit to what you can do with the spoken word. You cannot really do higher mathematics or even more complex forms of philosophical argument of the kind that I am interested in, unless you have some way of writing it down and scanning it. So it's not adequate to think of writing just as a way of recording, for the future, facts about the past and the present. On the contrary, it is immensely creative. "But now a second thing about writing, which I think is just as important as that, and that is when you write down you don't just record what already exists, but there are elements in which you create new entities. You create money, you create corporations, you create governments, you create complex forms of society, and writing is essential for all of that."

Writing seems to have emerged independently in Mesopotamia, Egypt, China and Central America - all of them expanding population centres - but there's fierce debate and much rivalry about who got to writing first. At the moment, the Mesopotamians seem to be in the lead, but that may simply be because their evidence - being in clay - has survived.

I began this week looking at how rulers, trying to control their subjects in the new populous cities of Egypt and Mesopotamia, used military force to coerce them. But in writing, they found an even more powerful weapon of social control. Even a reed pen turned out to be mightier than the sword.

Next week, I shall be looking at some of the new worlds that writing opened up - myth, mathematics and poetry.

-

![]()

Listen to the programme and find out more.