Could gene therapy herald a cure for haemophilia?

For decades we have been hearing about the promise of gene therapy – modifying someone’s DNA to correct errors that cause disease. Now, that promise is very close to being realised for one condition – Haemophilia A.

Haemophilia A affects about 8000 people in the UK, mainly men.

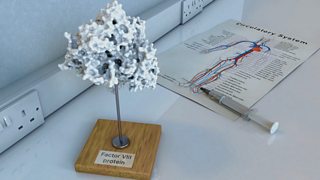

It’s caused by mutations in a single gene that contains the instructions our bodies need to produce a protein called Factor VIII, which allows our blood to clot.

Some haemophiliacs produce less than 1% of the amount of Factor VIII a healthy person will produce. For these people, a simple cut can cause severe bleeding, and there is a constant risk of spontaneous internal bleeding into joints, muscles and tissues, which can be painful and debilitating.

The condition is usually managed with regular injections of the missing Factor VIII protein – a routine that sufferers currently need to maintain throughout their lives.

Gene therapy

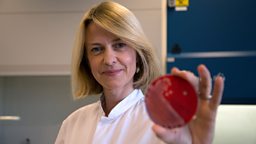

Gabriel Weston met Prof John Pasi of Barts Health NHS Trust in London, to find out about a series of clinical trials that have been using gene therapy to treat Haemophilia A. Scientists have known the gene responsible for making Factor VIII for years, but the challenge has always been how to get this DNA to the right part of the body – in this case to the liver where Factor VIII is produced.

The treatment being used in this trial was developed by scientists at BioMarin Pharmaceutical in California, and uses a virus as a ‘vector’ to deliver the genetic material to the right cells. The virus they’ve chosen is an adeno-associated virus, or AAV, that specifically targets the liver but doesn’t cause disease.

In the lab, the scientists strip out the virus’s own DNA and replace it with DNA that contains the missing instructions that the liver needs in order to make Factor VIII. The treatment is then given to the patient via an infusion.

The results so far have been impressive: in a phase 2 trial, patients saw their levels of Factor VIII rise to normal levels, meaning that their bleeding has stopped and they no longer need to give themselves regular injections. Now, Prof Pasi is helping to run a global trial which will test the therapy in over 100 patients. They hope is that this will help them to identify the optimal dose, and bring us closer to a cure for haemophilia.