Meet the scientists

The only way to become aware of the challenges that face baby animals in their first year, and ensure you have a chance to capture them on camera is to work alongside scientists who have studied the social interactions of their families in the field, sometimes for decades.

Between them, the scientists who helped us have more than two centuries of experience.

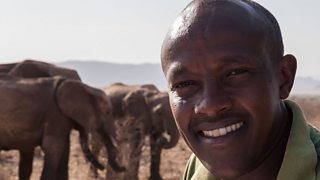

David Daballen & Save The Elephants

were the first conservation organisation to start radio-collaring wild elephants in Africa.

Now their GPS systems are so advanced they can not only pinpoint where migrating elephants are, but can also tell if might be in trouble with poachers or other forms of conflict with humans from changes in speed as they are travelling.

Head of Field Operations, David, has been working for Save the Elephants since 2000, and knows hundreds of elephants by sight and name.

Dr Martha Robbins & Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

Field Assistants - Dennis Musingunzi and Beda Turyananuka

Martha started out studying , in Rwanda, founded by Dian Fossey.

More than 20 years ago she moved on to the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda, and became the first scientist to begin long term studies of the gorillas there, and initially met resistance to the revelation that they climbed trees so much.

In her time at Bwindi, Martha has seen Nyakabara’s father, Mukiza, transform from a tiny baby into a 17-year-old silverback with his own troop.

Professor Kay E. Holekamp & The Mara Hyena Project, Michigan State University

Field researchers - Emily Nonnamaker and Kecil John

, and has supervised scores of research students in the field, including Emily Nonnamaker and Kecil John, who worked with team extensively throughout production.

The Mara Hyena Project welcomed the interest in and filming of the advanced maternal and social aspects of Spotted Hyenas because they generally these highly successful and resourceful mammals are so poorly and negatively represented.

Dr Michelle Steadler & The Monterey Bay Aquarium

Michelle joined the more than 30 years ago, when the number of wild Southern Sea Otters in California was only 1361.

It had been thought that the Southern Sea Otter had been hunted to extinction by the early twentieth century, and it was only when the new Pacific highway was constructed that an isolated population was discovered. Since then their numbers have slowly recovered.

In her time she has seen the population grow to more than 3,000, but then it reached a plateau. There may be many factors at play including the increase in numbers of Great White Sharks now that they are also protected, which may have led to an increase in juvenile Great Whites inadvertently killing sea otters.

Dr Wolfgang Dittus & The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute

Wolfgang came to Sri Lanka more than 50 years ago.

He established what is now the , which has uncovered the complex social interactions between these intelligent monkeys. Around 1,000 macques live in the abandoned, ancient capital of the island, and gain unofficial protection from its status as a World Heritage Site status, and benefit from the food they can pilfer and scavenge from the thousands of tourists visiting the ruined monasteries, palace and temples every year.

Dr Ester UnnsteinsdΓ³ttir & The Icelandic Institute of Natural History

Ester has been researching the .

This remote corner is the only place in Iceland where the foxes are protected, and every June she comes to the peninsula with an international team of volunteers to record which foxes have paired up, and how many cubs they have produced. She is just beginning a study on the effects of mercury on the foxes – mercury is a poisonous metal, which enters the food chain in the marine environment, travels into the fish that the seabirds eat, and then into the foxes that predate on seabirds.