Episode Transcript – Episode 35 - Head of Augustus

Head of Augustus (made 2,000 years ago). Bronze statue, found in MeroΓ«, northern Sudan

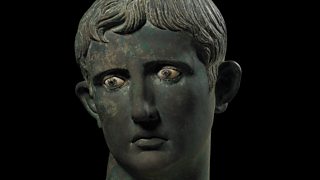

I'm looking into the eyes of one of the most famous leaders in the history of the world - Caesar Augustus, the first Roman Emperor. We have his bronze head here in the Roman galleries in the British Museum and, tarnished as it is, it radiates charisma and raw power. It is impossible to walk past. The eyes are dramatic and piercing. And wherever you stand, they won't look at you - he is looking past you, beyond you, to something much more important: his future.

"Well he was about the greatest politician the world has ever seen. If you wanted to have a first eleven of the world's leading politicians, most accomplished diplomats and ideologues of all time, you'd have Augustus as your kind of mid-field playmaker, captain of the eleven." (Boris Johnson)

The curling hair is short and boyish, slightly tousled, but it's a calculated tousle - one that clearly took a long time to arrange, because this is an image that has been carefully constructed, projecting just the right mix of youth and authority, beauty and strength, will and power.

"The portrait was very very recognisable, and very enduring. And it was a very successful marketing of an image because Augustus has never had a bad press." (Susan Walker)

His head is a bit over life-size, and tilts as if he's in conversation, so that for a minute you could believe that he's just like you and me - but he's not. This is the Emperor Augustus. He has recently defeated Anthony and Cleopatra, he has conquered Egypt, he is well on his way now to imperial glory, and is firmly embarked on an even greater journey - to become a god.

In this week's programmes we've been looking at how rulers commissioned objects that asserted their power - somewhat obliquely, and essentially by association. In China, the Han Dynasty used exquisite craftsmanship as an emblem of imperial wealth and order; in India, the Emperor Asoka invoked philosophical ideals. But in this programme we have something completely different - a ruler, the one in whose empire Christ was born, who quite simply projects himself and uses his own body and his own likeness to assert his personal power - the Roman Emperor Augustus.

His bronze, over life-sized head gives a brutally clear message: I am great; I am your leader and I stand far above everyday politics. And yet, ironically, we have this commanding head here at the Museum only because it was captured by an enemy and then humiliatingly buried. The glory of Augustus is not quite as unalloyed as he wanted us to believe.

Augustus was Julius Caesar's great-nephew. The assassination of Caesar in 44 BC left Augustus the heir to his fortune and to his power. He was only 19, and he was suddenly catapulted into a key role in the politics of the Roman Republic. Known at that point as Octavian, he quickly outshone all his peers in the scramble for absolute power.

The pivotal moment in his rise was the defeat of Mark Anthony and Cleopatra at the battle of Actium in 31 BC. Already holding Italy, France, Spain, Libya and the Balkans, Augustus now followed the example of Alexander the Great and seized the richest prize of them all - Egypt. The immense wealth of the Nile kingdom was now at his disposal. He made Egypt part of Rome - and then turned the Roman Republic into his personal empire. Across that empire, statues of the new ruler would now be erected. There were already hundreds of statues portraying him as Octavian, the man-of-action party leader, but in 27 BC the Senate acknowledged his political supremacy, and awarded him the honorific title of Augustus - "the revered one". This new status called for a quite different kind of image, and that is what our head shows.

Our head comes from this time, a year or two after Augustus became emperor. It was once part of a full-length statue that showed him as a warrior, slightly larger than life-sized. It's broken off at the neck but otherwise the bronze is in very good condition. It's an image that in one form or another would have been familiar to hundreds of thousands of people, because statues like this were set up in cities all over the Roman Empire. This is how Augustus wanted his subjects to see him. And although every inch a Roman, he wanted them to know that he was also the equal of Alexander and heir to the legacy of Greece. The distinguished Roman historian Susan Walker explains what is going on:

"When he had become master of the Mediterranean world and took the name Augustus, he really needed to find a new image. And he really couldn't copy Caesar's image, because Caesar looked like a crusty old Roman. He had a real warts-and-all portrait - very thin and scraggy, and bald, and very austere, very much in the manner of traditional Roman portraiture. So that image had become a little bit discredited, and in any case Augustus - as he now was - was setting up an entirely new political system, so he needed to have a new image to go with it. And having assumed this image when he was still in his thirties, he stayed with it until he died aged 76, so there's no suggestion in his portraits, even any subtle suggestion such as we see in the portraits of our Queen, for example, of any aging process at all."

This was an Augustus forever powerful, forever young. His deft, some might say devious, mix of patronage and military power, which he concealed behind the familiar offices and titles of the old Republic, has served as a model and a master-class for ambitious rulers ever since. He built new roads and developed a highly effective courier system, so that the empire could be effectively ruled from the centre and so that he could be visible to his subjects everywhere. He reinvigorated the formidable Roman army to defend and extend the Imperial borders, and he established a long-lasting peace during his 40 years of steady rule, initiating a golden period of stability and prosperity famously known as the 'Pax Romana'. He'd brutally fought and negotiated his way to the top, but now he was there, he wanted to reassure people that he would not be a tyrant. So he set to work to make people believe in him, and more astonishingly want to follow him, brilliantly turning subjects into supporters. We asked Boris Johnson, a classicist and a political leader, how he rated Augustus:

"He became a vital part of the glue that held the whole Roman Empire together. You could be out there in Spain or Gaul or Cyrenaica - you could be all over the world - and you could go to a temple and you would find women, with images of Augustus, of this man, in this bust sewn onto their cowls. People at dinner parties in Rome would have busts exactly like this above their mantelpieces - that was how he was able to infuse the entire Roman Empire with that sense of loyalty and adherence to Rome. If you wanted to become a local politician, in the Roman Empire, you became a priest in the cult of Augustus."

It was a cult sustained by constant propaganda. All across Europe, towns were named after him. The modern Zaragoza is the city of Caesar Augustus, while Augsburg, Autun and Aosta all derive from Augustus. His head was on coins, and everywhere there were statues. But the British Museum's head is a head from no ordinary statue, it takes us into another story - one that shows a darker side of the Imperial narrative, for it tells us not only of Rome's might, but of the problems that threatened and occasionally overwhelmed it.

This head was once part of a complete statue that stood on Rome's most southerly frontier, on the border between modern Egypt and Sudan, probably in the town of Syene near Aswan. It's a region that has always been a geo-political fault line, where the Mediterranean world clashes with Africa. In 25 BC, so the writer Strabo tells us, an invading army from the Sudanese kingdom of Meroe, led by the fierce one-eyed queen Candace, captured a series of Roman forts and towns in southern Egypt. Candace and her army took our statue back to the city of Meroe and buried the severed head of the glorious Augustus beneath the steps of a temple dedicated to victory. It was a superbly calculated insult. From now on, everybody walking up the steps and into the temple would literally be crushing the Roman Emperor under their feet. And if you look closely again at the head, you can see tiny grains of sand from the African desert still embedded in the surface of the bronze - a badge of shame still visible on the glory of Rome.

But there was further humiliation to come. The indomitable Candace sent ambassadors to negotiate the terms of a peace settlement. The case ended up before Augustus himself, who granted the ambassadors pretty much everything they asked for. He had secured the Pax Romana, but at a considerable price. It was the action of a shrewd, calculating political operator, who then used the official Roman propaganda machine to airbrush this setback out of the picture.

Augustus's career became the imperial blueprint of how to achieve and retain power. And a key part of retaining power was the management of his image. Here's Susan Walker again:

"He always looked exactly as he did on the day that he became 'Augustus', and he presented himself very modestly. He often showed himself wearing the Roman toga, and drew it over his head to show his piety. And sometimes he was shown as a general leading his troops into battle, even though he never actually personally did so. And this was a very enduring image; we have surviving even today over 250 images of Augustus, which come from all over the Roman Empire, and they are pretty much the same - the variations are really not very significant. So the portrait was very, very recognisable, and very enduring."

This eternal image would be coupled with an eternal name. After his death, Augustus was declared a god by the Senate, to be worshipped by the Romans. His titles Augustus and Caesar were adopted by every subsequent emperor, and the month of Sextilius was officially renamed August in his honour. Here's Boris Johnson again:

"Augustus was the first emperor of Rome, and he created from the Roman Republic an institution that in many ways everybody has tried to imitate for the succeeding centuries. If you think about the Tsars, the Kaiser, the Tsars of Bulgaria, Mussolini, Hitler and Napoleon, everybody has tried to imitate that Roman iconography, that Roman approach, a great part of which began with Augustus and the first 'principet' as it was called, the first imperial role that he occupied."

All through this week, we've been looking at how a few privileged individuals imposed their will on the world around them. Next week, we'll still be looking at the world in the time of the Pax Romana, but the objects will be focussing on the passions, pastimes and appetites that have always governed more ordinary people's lives. It will be a week of vices, and spices. And we begin with a silver cup, made for a pederast in Palestine.

-

![]()

Listen to the programme and find out more.