Episode Transcript – Episode 87 - Hawaiian feather helmet

Hawaiian feather helmet (made in the eighteenth century)

In 1778 the explorer Captain James Cook was in the Pacific, on board 'HMS Resolution', looking for the North West Passage, hoping to find a sea-route over the north of Canada that would connect the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. He didn't find the North West Passage, but he did re-draw the map of the Pacific. He was charting coastlines and islands, collecting specimens of plants and animals. In 1778, he and his crew landed in Hawaii, returning again early in 1779. It's impossible for us to imagine what the islanders made of these European sailors, the first outsiders to visit Hawaii for over five hundred years. Whoever the Hawaiians thought Cook was, however, they presented him with the gift of a chieftain's helmet - a rare and precious object made of yellow and red feathers. Cook recognised it as an acknowledgement by one ruler of another, a clear sign of honour. But a few weeks later, Cook was dead . . . killed by the same people who'd given him the helmet. Something had gone drastically wrong.

"The object is enormously significant as an expression of a particular moment, of the very beginnings of European contact with Hawaii, the very beginnings of a complex, very troubled history - marked by moments of generosity and respect, but also violence, misunderstanding, long-term cultural damage." (Nicholas Thomas)

"The idea that this is for the future, so that everyone can understand the way that the Hawaiian people experienced the world, as well as how they want to share that." (Marques Hanalei Marzan)

This week of programmes is about the kinds of communication and miscommunication that can, perhaps must, happen when different worlds collide. In the eighteenth century European explorers, Cook above all, set about accurately mapping and charting the oceans, especially the huge and unknown Pacific. Before the Egyptian mummies arrived at the British Museum, the objects from Cook's voyages in the South Sea were what everybody wanted to see - glimpses of a new and other world. And one of the prize objects in the collection has always been the Hawaiian feathered helmet.

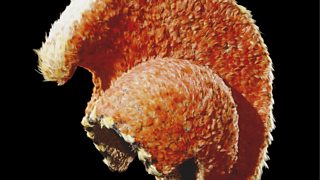

The helmet is man-size, and it would be very tempting to see if it fitted, but sadly, it is so delicate that I'm not allowed even to touch it! It's entirely covered in red, yellow and - here and there - black feathers, that could come off at the slightest movement. It looks like an Ancient Greek helmet that fits very close to the head, but with a thick, high crest running over the top from front to back, rather like a Mohican haircut. The sides and the body of the helmet are brilliant scarlet. The top of the crest has alternate rows of yellow and red feathers, and the front edge has a thin edging of black and yellow. It's vivid, radiant, and the wearer would instantly have stood out from the crowd. The red feathers come from the 'i'iwi' bird - a species of honeycreeper - the yellow feathers from a honeyeater, which has mostly black plumage but also a few yellow feathers. These tiny birds were caught and then either plucked and released, or simply killed. The feathers were then painstakingly attached to a fibre netting, moulded onto a wickerwork frame.

Feathers were the most valuable raw material at the Hawaiians' disposal, their equivalent of turquoise in Mexico, jade in China or gold in Europe. This is a helmet in every way worthy of a king, and it probably belonged to the overall chief of Hawaii Island, by far the largest of the Hawaiian archipelago, which lies around two thousand miles (3,200 km) off the American mainland. Polynesians had settled the islands by about 800, part of that great ocean-going campaign which also settled Easter Island and New Zealand. But it seems that from about 1200 to 1700 they were utterly isolated. As I said, Cook was the first stranger to visit for five hundred years. So he was probably less surprised by them, than they by him. In spite of their long isolation, the Hawaiians' social structures, customs and agriculture, although superficially exotic, nonetheless seemed to make sense - almost indeed to be familiar - to the Europeans. The anthropologist and expert on Polynesia, Nicholas Thomas, explains:

"When Cook arrived in Polynesia, in particular, he encountered societies that struck Europeans as possessing their own sophistication. In Hawaii in particular, extraordinary kingdoms had emerged that embraced whole islands, and that were caught up in complex trading relationships among different islands. They were encountering complex and dynamic societies, with aesthetics and cultural forms that impressed Europeans in all sorts of ways. How could such cultural practices exist in places that were so remote from the great centres of classical civilisation?"

In many ways, Hawaii seemed not unlike eighteenth-century Europe. A large population was ruled by an elite of chiefly families and priests. Under these families came the professionals . . . craftsmen and builders, singers and dancers, genealogists and healers who, in turn, were supported by the main population, who farmed and fished. The maker of the feathered helmet would have been a professional craftsman. The cultural specialist Kyle Nakanelua from Maui, Hawaii, has examined the helmet:

"Figure four of those feathers from one bird at a time . . . you can pick 'em. So that looks like about 10,000 feathers, so divide that by four you get how many birds at one given time? Now, again we're talking about the rank and the status of the chief. So, this chief has a retinue of people with the occupation of collecting feathers, storing feathers, caring for these feathers, and then manufacturing them into these kinds of products. So you're talking about anywhere from a hundred and fifty to two hundred people. It could have been that they could have been collecting these feathers for generations, before putting one of these articles together . . . that's a pragmatic understanding of this symbol of wealth and power."

Chiefs put on feather helmets and capes to make contact with the gods - when making offerings to ensure a successful harvest, for instance, or to avert disasters such as famine or illness, or to propitiate the gods before a fight. The feather costumes were the equivalents of the great helmets and coats-of-arms of European medieval chivalry - highly visible ceremonial clothes worn by chiefs to lead their men into battle. Above all, these costumes gave access to the gods. Made from the feathers of birds - themselves spiritual messengers and divine manifestations - they gave the person who wore them supernatural protection and sacred power. Here's Nicholas Thomas again:

"Feathers were particularly sacred - not just because they were pretty or attractive. They were associated with divinity. Legends often had it that gods were born, they emerged as bloody babies covered in feathers, they were saturated - in a sense - with divine power, with associations from the other world - particularly when they came in sacred colours of yellow and red."

These ideas were not so strange to Cook. Of course, English kings weren't born covered in feathers, but they were divinely anointed monarchs, who carried out priestly functions in elaborate ceremonial robes, in a cult where the Holy Spirit was represented by a bird. In fact, Cook seems to have "read" Hawaiian society as essentially like his own, but he could not grasp their very different sense of the sacred.

When Cook first arrived at Hawaii, it was during a festival devoted to the god Lono, in the season of peace. He was given a grand reception by the paramount chief. A vast red feather cape was thrown round him, and a helmet placed on his head. He spent a month peacefully on the island repairing his ships and taking precise measurements of latitude and longitude. Then he left to sail north, but a month later a sudden storm forced him back to Hawaii, and things then went very differently. It was now the season devoted to Ku, the god of war. The local people were much less welcoming, and incidents broke out between them and Cook's crew, including the theft of a boat from one of Cook's ships. Cook planned a tactic that he'd used before. He decided to invite a chief on board his ship, and hold him hostage until the missing items were returned. But as he and the chief walked on the beach, the chief's men raised the alarm, and in the ensuing mοΏ½lοΏ½e Cook was killed.

What happened? Did the Hawaiians first think that Cook was a god, as some suggest, who was then later unmasked as being only a human? We don't know, and the circumstances of Cook's death have become a text-book study in anthropological misunderstandings. But the islands were permanently changed by his arrival. European and American traders brought deadly disease, and missionaries transformed the islands' cultures. Hawaii itself was never colonized by Europeans. Instead, a local chief was able to use the trading contacts inaugurated by Cook to create an independent Hawaiian monarchy, which survived for over a century until its annexation by the United States in 1898.

I began this programme wondering how far it's ever possible to understand a totally different society, and it is a difficulty that greatly exercised eighteenth-century travellers. The surgeon who sailed with Cook on 'HMS Discovery' mused upon the problems of communication with this other strange world, as he recorded his observations with admirable humility:

"There is not much dependence to be placed upon these Constructions that we put upon Signs and Words, which we understand but very little of, & at best can only give a probable Guess at their Meaning."

It's impossible to know exactly what objects like this feather helmet meant to Hawaiians of the 1770s, but what is clear is that they are now taking on a new significance for Hawaiians of the twenty-first century. Here's Nicholas Thomas again:

"It's an expression of that oceanic art tradition, but it also expresses a particular moment of exchange that marked the beginnings of a very traumatic history, that in some ways is still unfolding. Hawaiians are still affirming their sovereignty, and trying to create a different space in the world."

And for Hawaiians themselves, like the cultural specialist Kaholokula, these feathered objects take their place in a very particular contemporary political debate.

"It's a symbol of what we lost, but a symbol of what could be again for Hawaiians today. So it is a symbol of our chiefs, it's a symbol of our lost leadership and our lost nation, and it's interesting that most of the 'mahiole' [feathered helmets] that exist today from the 1800s exist outside of Hawaii. So it's a symbol of loss for the Hawaiian people, but it's also encouragement for the future, and the rebuilding of our nation, as we seek independence from the United States."

In the next programme, we move to the continental United States, or what would soon become the United States, with a map that charts a different, and equally complex, relationship between local inhabitants and European intruders. It's a map that shows large areas of the northern mid-west . . . laid out on the skin of a deer.

-

![]()

Listen to the programme and find out more.