First whalefall study in the deep Atlantic

By Will Ridgeon, Assistant Producer on The Deep

For The Deep episode, we wanted to show what happens to a whale after it dies – how its body sinks and becomes the basis for an entire deep-sea ecosystem. A whalefall, as it’s known by deep sea scientists, is a vital source of food for many creatures of the deep. Scientists think there could be a whale carcass every 20km on the seabed – but, in the pitch-black, where the sun never shines, how were we ever going to find one, let alone film it?

We forged a collaboration with scientists at the University of Azores interested in a long-term study and the Rebikoff-Niggeler Foundation who have studied the deep seabed around the Azores. Together, we formulated a plan to be the first team to observe what happens to a whale’s body in the deep Atlantic Ocean. After months of preparation, planning and putting essential and complex logistics in place, we got the phone call - a dead sperm whale had been found off the coast of the Azores. It was being devoured by blue sharks and, should enough blubber be eaten, it could sink of its own accord at any moment. We had to react quickly.

Arriving on location, our first reaction was one of sadness. We have spent a lot of time filming sperm whales for the series and have been privileged to witness touching moments in their lives. To see this magnificent animal reduced to rotting flesh was hard, especially as it was likely that this animal had died as a result of humans – quite possibly an accidental collision with a large ship. Ship strikes are an increasing problem for whales in the ever-busier oceans.

But in this beautiful creature’s death, there was hope of learning something new about the ocean. We worked with the team to attach scientific instruments and a radio transponder. After rocks were added as weight, the whale began its journey to the dark abyss, over 700 metres below.

Now we just had to find and film the carcass in the inky depths. By 200 metres deep, only a very faint blue light is left. Below 300 metres, it is completely dark. After descending for 45 minutes, the barren, muddy bottom appears. Our initial fears that the transponder would fail were quickly replaced with elation: its pinger was very clear. The whale was close. By keeping the sub pointing in the direction of the signal, we made our way across the empty plain. But after 15 minutes following the noise, the signal went dead. The sub’s lights only penetrate 10 metres into the darkness ahead – what to do now! Thankfully, while trying to come up with a plan B, a huge sixgill shark swam past. These deep sea specialists have highly attuned senses so we followed its lead through the gloom to a huge dust cloud. The visibility was zero but eventually, out of the murk, the distinctive shape of the sperm whale’s body appeared. The shark had guided us to it… but we weren’t the first.

There was already a massive sixgill sharks ripping into the carcass, sending plumes of blood into the water. In the sub’s lights, the whole scene turned deep red. Each shark is as big as a great white (not far off the length of our submersible) and the force of their bites shook the 30 tonne carcass like a rag-doll.

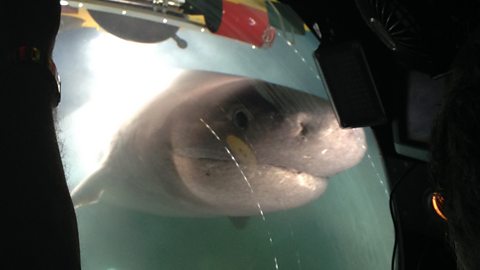

It has been hypothesised (probably because only single sharks have previously been found on whalefalls) that these sharks defend a carcass from others like a territory, and these sharks were certainly aggressive – biting and bumping each other. It was a very unnerving place to be. And as more sharks arrived, they began to turn on the sub, bumping and biting at the acrylic dome and pushing us around. The sub is very sturdy, but you can’t help wonder what damage these powerful sharks are inflicting – even the experienced pilot Joachim admitted he was a little afraid!

The sharks quickly realised the sub was not competition and their attention returned to the carcass and camerawoman Kirsten was able to film the first deep-sea, sixgill shark feeding frenzy ever witnessed. After 4 hours and with the sub’s batteries depleted, we began our long ascent to the surface, leaving the sharks to their meal.

We later learned from the camera that had been attached to the whale carcass before it was sunk, that the first sixgill had arrived on the scene just 25 minutes after the carcass landed on the seabed – a revelation for the science team.

We continued to film the carcass for the next year, documenting the incredible ecosystem that relies on the whale carcass and even now, scientists are still studying the site, learning more about this vital process that feeds so many creatures of the deep in the first ever long-term study of this phenomenon in the Atlantic Ocean.

Sub vs shark

At a depth of 700 metres, a Blue Planet II sub is shoved by some enormous sixgill sharks.