Is a personalised diet the secret to long-term health?

Many of us take dietary rules for granted. Like eating little and often, not skipping meals and keeping a check on our calorie intake. But genetic epidemiologist, Professor Tim Spector, argues we need to re-evaluate what we think we know about a good diet.

In The Life Scientific, he tells Jim Al-Khalili how diversity in the types of food we eat and in the unique mix of microbes we nurture in our gut is the most important factor for health – and can even defend us against COVID-19. And how personalised nutrition may just hold the key.

Look after your gut, he urges, and it will look after you.

-

![]()

Listen to The Life Scientific

Professor Jim Al-Khalili talks to leading scientists about their life and work.

βWeβre much more different than weβve been led to believeβ

Tim founded the UK Twins Registry at Kings College London to unravel the extent to which our genes contribute to a vast range of human conditions and diseases. Over 13,000 pairs of twins have contributed to the research.

No two peopleβs vast repertoire of gut bacteria β even in identical twins β is the same.

The scientist became interested in why identical twins – with identical genetic make-up – often die of different diseases. “What was it about those identical clones that would force them down different routes of personality or disease?” he asked. He began to look into epigenetics: the power of outside factors on the way genes can get switched on and off.

But epigenetics couldn’t explain all of the differences they were seeing. Weight between twins could differ by up to 10kg, for example. “We could explain only a small part of that 10kg difference with the epigenetics,” says Tim, “so we knew there was something going on that wasn’t down to the genes.”

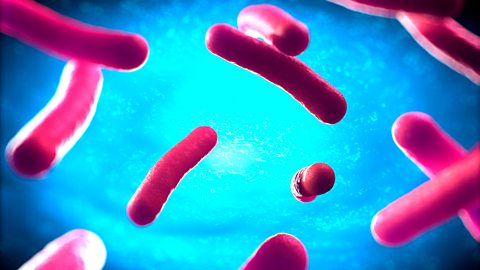

Tim and his team hunted for another explanation and made a fascinating discovery: “The one thing that really came up most was that they really differed in their gut microbes,” says the scientist.

The gut microbes are like βa chemical factoryβ in the body

No two people’s vast repertoire of gut bacteria – even in identical twins – is the same, says Tim.

“If you think of them as an organ in your body that’s like a chemical factory, that differs between all of us, suddenly you start to understand why a lot of where we’ve gone wrong over the last thirty years in nutrition suddenly starts to make sense.”

“All of us know that some people have responded to some diets, others not, and yet we’ve got this sort of dogma that we must all be the same and if we fail to lose weight it’s our fault,” he says. But it’s our unique mix of gut bacteria that dictates our highly individual responses to different foods, he argues.

Why you need to get to know your body's microbes

They're not just germs. They influence our bodies more than we know.

Certain microbes in the gut can stop us getting fat

Tim asked twins in the study to provide stool samples, so they could measure their microbes. They collected lots of these samples, sequenced them, and then looked at twins where one was overweight and one was skinny.

We found in every case the skinnier twin had a more diverse microbiome - greater numbers of different species of microbes.

“We found in every case the skinnier twin had a more diverse microbiome (greater numbers of different species), and they also nearly always had high numbers of a couple of microbes that just stuck out of the crowd,” says Tim. They go by the name of Christensenella and Akkermansia.

“It turns out that these are really beneficial microbes,” says Tim. When they put Christensenella into sterile mice, they could “stop them getting fat” – an association that has been confirmed by several other similar projects. “This is showing that a beneficial microbe can have an effect on our guts to in some way change our metabolism to stop us putting on weight.”

“There’s probably hundreds of thousands of microbes or strains like that that in combination can have this beneficial effect,” he says.

A more diverse diet means more diverse microbes

To ensure we have diverse gut microbes, we need a diverse diet, says Tim.

“We found that the optimum diversity, across 11,000 people, was whether you ate 30 plants a week or not.” That sounds like an awful lot, he admits, but this doesn’t mean drinking 30 kale smoothies a week. The key is to “go back to biology” and remember what a plant really is. “It’s also a peanut, it’s a seed, it’s a bit of turmeric,” says the scientist, “and each plant will help promote the growth of a different set of bacteria or strains of bacteria.”

“It’s this diversity of our diet of unprocessed, different foods, that was the best predictor of a healthy gut. It didn’t matter if you were vegan, vegetarian, keto, intermittent faster,” he states. “This was the thing that you need to have on your plate. Once you got that, you could do anything else.”

Weβre βbrainwashedβ into thinking all calories are equal

Tim’s next step was to see how individuals responded differently to the same foods. He co-developed and launched the ZOE app, based in London and Boston, which aims to provide “personalised nutrition.”

They did a giant study on over 1000 people, many of them twins, in which they gave participants an identical muffin, told them to eat the muffin at exactly the same time of day and within a certain amount of time, and then looked at their responses using glucose monitors and fat monitors. They also examined their microbiomes.

The results were extraordinary. “We saw a tenfold difference in the rise in glucose or the rise in insulin, and a quarter of those people at three hours had a sugar dip,” says Tim. “When we looked over the next 24 hours, we saw that the next meal they were hungrier, they reported being more tired, and they ate about 300 more calories in that day.”

We’re “brainwashed” into thinking all calories are equal, but the findings blew away that concept, says Tim.

Microbe-boosting breakfast

For Tim’s breakfast of choice, he takes full fat Greek yoghurt, which is probiotic and “really good for your bugs”; adds kefir, which is fermented milk and a “super yoghurt”; and tops with a good mixture of berries, nuts and seeds.

Voilà! Ten plants in in one breakfast.

-

![]()

Listen to The Life Scientific

Professor Tim Spector on fuelling gut microbes for long term health.

Which foods make your gut happiest?

Dan Saladino discovers the world of the gut microbiota.

Is βpersonalised nutritionβ the future?

The team pulled all the data together so they would have something they could give to the public as a home test kit, and it’s now been successfully launched in the U.S..

People who sign up for the ZOE app are sent the muffins and the continuous glucose monitor, which they put on themselves. They prick their finger to look at the blood fats after a meal, and they send in a stool sample. They then log all their foods for two weeks.

The results that users submit are then put through massive computers and using artificial intelligence they come up with an algorithm that then scores all the common foods they might eat “for them, personally, based on their results,” explains Tim. They can then eat using this score as a guideline. “If you know what foods are going to give you a sugar dip, you can avoid them.” But really, nothing is excluded, says Tim. We just say ‘please eat more of this.’”

-

![]()

The Gut Instinct: A Social History

Tim Hayward journeys through the bowels of history.

-

![]()

Frontiers: Gut Microbiota

New insights into the important relationship we have with microbes that live in our gut.

A good quality diet might reduce the severity of COVID

When the pandemic struck, The ZOE team were able to very swiftly adapt the technology to help shed light on the spread of COVID and the different symptoms that people were developing. It became known as the . Within 24 hours a million people had downloaded it, and up to four and a half million people have now used the app. “It’s a unique citizen science project,” states Tim.

The quality of the diet people were on, not the calories, was instrumental in reducing the severity of COVID: the number of hospitalisations or people who had long-term symptoms.

Tim has now turned his attention to how diet can influence COVID outcomes. “Because we had this amazing database of people, we decided to do a mass diet quality survey in the U.S. and the U.K.,” he explains. They had over a million people reply.

Results showed that “the quality of the diet people were on, not the calories, was instrumental in reducing the severity of COVID: the number of hospitalisations or people who had long-term symptoms.”

This should be a wake-up call, argues the scientist. “Everything starts to come together about the importance of your diet on your immune system via your gut microbes, and how this has been so neglected.” He poses that the reason why the U.S. and the U.K. “have done so badly in terms of hospitalisations and deaths from COVID, compared to other countries, could well be just the high levels of ultra-processed foods that we’re eating, which are still being labelled as healthy.”

“We know diet is important in immune function,” says Tim. “We know that diet quality has an effect on the gut microbiome, and we know that the microbiome and the immune system are absolutely linked.” The data is observational, has flaws, and “absolutely needs a randomised control trial,” he admits, “but if I was advising people now, I don’t think it’s really dangerous to say your diet quality is one of the things we can all do to improve our health and reduce risk of COVID.”

The information contained in this article was correct at the time of broadcast on 19 October 2021.

Listen to The Life Scientific to learn more about the need for personalised diverse diets and how by looking after your gut, it will look after you.

-

![]()

The Life Scientific

Professor Tim Spector on fuelling gut microbes for long term health.

-

![]()

Seven myths about food that have fooled us all

Unpicking the myths β Tim Spector argues that most of what we know about food is wrong.

-

![]()

Eat Some Bacteria

How fermented foods might be the key to a healthy brain, body and mind.

-

![]()

How what you eat affects your immune system

Many of us are keen to find ways to boost our immune systems. But what actually works - and what is safe?