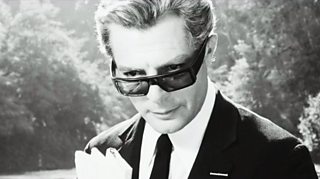

Cinema giant Orson Welles at 100

6 May 2015

This month marks the centenary of one of the greats of cinema, Orson Welles, and fittingly his 100th birthday is being marked by a range of new releases. WILLIAM COOK takes a look at Touch of Evil and Falstaff: Chimes at Midnight.

There’s a smart new documentary, directed by Oscar winning filmmaker Chuck Workman, and a season of Welles' movies at the BFI this summer, but in the meantime you can see his favourite film, Falstaff: Chimes At Midnight, on the big screen.

Human to the core... an inspiring piece of cinemaSimon Callow

‘If I wanted to get into heaven on the basis of one movie, that’s the one I’d offer up,’ said Welles.

Welles’ biographer, the actor Simon Callow, agreed. ‘An absolute essence of Shakespeare and an absolute essence of Orson Welles,’ said Callow.

Callow called it Welles’ masterpiece, one of the great achievements of 20th Century filmmaking. Watching it again today it’s hard to disagree.

Starring Welles as Falstaff, alongside John Gielgud and Margaret Rutherford, the film influenced Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V and Mel Gibson’s Braveheart.

Callow called Falstaff: Chimes At Midnight ‘human to the core,’ and it’s this humanity which makes it such an inspiring piece of cinema.

Welles’ Falstaff is ridiculous, but he’s also magnificent – a real man, meandering, as we all do, between triumph and humiliation.

As Welles said of Shakespeare, ‘It’s a great feeling to be dealing with material that’s better than yourself.’

Watch scenes from Falstaff: Chimes at Midnight

Touch of Evil

Falstaff: Chimes At Midnight isn’t the only centenary treat in store. The highlight of the n is Touch of Evil, Welles’ masterful film noir, made in 1958.

There's a kind of maverick streak in Orson... there's something in him that drives him to alienate the people with the moneyCharlton Heston

It’s a film which encapsulates his expressionistic directing style, and his troubled relationship with Hollywood.

‘I always liked Hollywood very much,’ he said. ‘It just wasn’t reciprocated.’

Having hired Welles to play a hardboiled cop, the film’s producer asked Charlton Heston to co-star. Welles was already in the autumn of his career. Heston was a bigger draw. Heston said he’d do the picture if Welles directed it. Welles said he’d direct it if he could write the script.

Touch of Evil was wonderful (especially Welles’ central performance, as a corrupt but brilliant policeman) yet, as so often in his career, Welles fell out with the moneymen.

‘They loved the rushes but then they saw a rough cut,’ recalled Welles. ‘They were so horrified they wouldn’t let me in the studio.’

Welles was fired from the movie. Universal recut Touch of Evil to suit their tastes, with several new scenes. Welles wrote an impassioned 58 page memo, outlining the way he thought the film should be. His pleas were ignored.

Thankfully the version you’ll see in the cinema this summer comes as close as possible to the movie Welles (rather than Universal) envisaged. Uniquely, for a director’s cut, it’s actually shorter than the original.

Welles and the studios

Why did Welles find it so hard to work within the studio system? Because he was an artist of genius, not a workaday committee man.

As Charlton Heston said, ‘There is something in him that drives him to alienate the people with the money.’

Welles ended up making his own movies, with his own money, but this merely gave him a different set of problems.

His moody production of Othello, shot in Morocco, dragged on for four years, as Welles shut down the production to raise the cash for each new phase of filming. By the time he wrapped, he’d ended up with a completely different Desdemona.

The pity of this piecemeal approach was that many of Welles’ finest projects remained unfinished, such as his austere Don Quixote and his haunting Merchant of Venice.

Yet despite his perpetual struggles with the studios to let him make his films his way, he left us so much to relish, including The Lady From Shanghai, The Third Man and .

Hollywood never found a way to utilise Welles’ immense talent. During the last 15 years of his life, he directed no movies and played no major roles.

His screen career had shrunk to film cameos and TV chat shows, but he didn’t seem to care. Like Peter Ustinov, Welles felt at home all over Europe. Like Ustinov, he was a brilliant (if inaccurate) raconteur.

‘Working for posterity is vulgar, because posterity is just as big a whore as the present,’ he said. ‘That’s why we enjoy life - because we know it’s got to end.’

Welles sometimes slummed it in other people’s films, but he never prostituted his own movies, so posterity has been kind to him, much kinder than the studios.

‘Plato told us we should know ourselves,’ said Welles, not long before he died. ‘The object of every artist - good, bad or indifferent - is a lifelong enquiry into that subject.’

Good or bad (but never indifferent) Welles’ films never shy away from asking the big questions about the human condition, and that’s why they still move us. Born on 6th May 1915, Orson Welles died, aged seventy, on 10th October 1985. Happy Birthday. RIP.

is in cinemas now; is on general release in July.

Orson Welles at 100

-

![]()

10 things most people don't know about the film that tops the all-time lists of many film critics - Welles' first movie

-

![]()

Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Arts collects the series of talks by film director Orson Welles, illustrated by his own sketches

More Film from Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Arts

-

![]()

Celebrating the centenary of cinema giant Orson Welles

-

![]()

What made this surreal mishmash such a great film?

-

![]()

Carol Morley on the real life inspirations for her latest film

-

![]()

The painstaking handiwork behind the sci-fi classic's visuals

-

![]()

Exploring the myths around the Nirvana frontman

-

![]()

Gene Vincent's disastrous 1969 tour of the UK

More films

Film features & archive from Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Arts plus reviews and more from around the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ