The big motivation experiment

Many of us have a desire to eat more healthily and be more active but it can be difficult to make the necessary changes, particularly ones that will last.

So what can we do to help ourselves achieve these goals?

When it comes to eating well and moving more most of us know what we ought to do, the problem is actually doing it, and there’s a lot at stake – not only would maintaining these good intentions help us lose weight and feel good, it would also reduce our risk of developing things like diabetes, heart disease, stroke and cancer which are all linked to obesity and inactivity.

That’s why we turned to a pair of behavioural change specialists for advice - Claire McDonald, who advises the NHS and Royal Society of Public Health, and Ed Gardiner, from the University of Warwick.

The Big Activity Experiment

One of the big problems with becoming more active is that there are lots of distractions in life pulling us in other directions – we’re busy, time is limited and we have established habits that are very hard to break. What’s more, the environments in which we live and work are not usually designed to help us. So Claire and Ed drew on behavioural science to come up with tactics that could help us move more during the working day, and we put them to the test on three groups of volunteers who all worked at Derby University:

Group 1 were our control group. They were given public health messages about the benefits of activity.

Group 2 were our competitors. They were told to compete against each other for prizes and were given regular feedback on their progress.

Group 3 were our cooperators. They were given a group target that they had to achieve together.

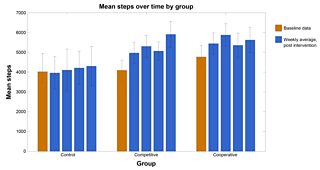

We measured our volunteers’ baseline activity levels for a week using pedometers, step counters and apps and then ran our intervention for a month.

The tactics

Rather than trying to make big commitments like joining gyms or taking up sports Claire and Ed wanted our volunteers to make lots of smaller, easier changes that they could knit into their existing lives. This way, there would be more chance of them forming new habits which had the potential to last. The instructions our volunteers were given were:

- Take the stairs, not the lift. Believe it or not, stair climbing can burn more calories than jogging, so we installed timely reminders in the office at the point at which people had to decide between the stairs and the lift to encourage them to choose the stairs.

- Walk to see colleagues instead of emailing them.

- Park further away from the office, get off the bus a stop early or find a longer route to walk to work.

- Go for a lunchtime stroll, or buy lunch further away so that you have to walk.

- Have walking meetings instead of sitting in a meeting room.

- Try walking around or standing when making or taking phone calls.

The results

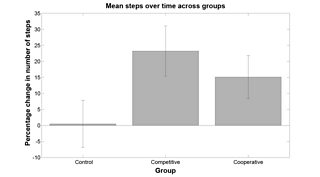

After four weeks the activity levels for our control group had only improved by 3%, suggesting that information alone is not enough to change behaviour.

In contrast, our cooperators improved by 16% and our competitors by 30%, but these average improvements concealed a lot of variation within both groups.

While the competitive group contained the top two scorers, there were also people who only improved by a small amount.

This reflects the fact that in competitive environments those who are doing better than the average are likely to feel motivated and continue their improvement, whereas those who find themselves below the average can feel demoralised and give up.

This is less of an issue in cooperative situations where even those who are below average still feel motivated because they are contributing to an overall goal.

The other interesting thing we found was that once our cooperative group improved, their averages remained steady week on week, whereas our competitors were improving more and more each week as they jostled to lead the rankings.

What both these groups had in common though, was social interaction. In behavioural science there is a concept called ‘social proof’ where committing to doing something with others means we’re more likely to do it.

Part of this could be the fact that once we’ve openly committed to something we don’t want to publically fail, but another aspect is that social activities are more enjoyable and fun and we’re therefore much more likely to stick to them.

Whether someone would best thrive in a cooperative or competitive environment comes down to character and personal preference, but whether you prefer being a competition winner or a team player, social involvement and shared targets will provide better motivation than going it alone.