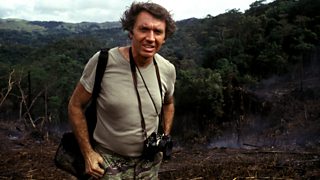

War and peace: The compassionate photography of Don McCullin

4 February 2018

From civil unrest to the enduring beauty of the English landscape, 83-year-old photographer Sir Don McCullin has captured a huge range of subjects. With a new documentary for Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Four and a retrospective at Tate Britain, WILLIAM COOK speaks to the self-styled ‘travelling inquisitor’.

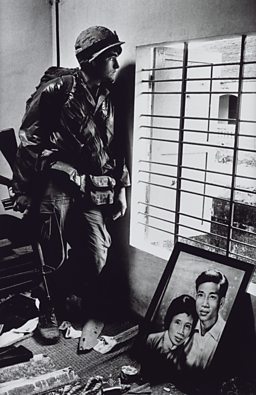

Don McCullin hates being called a war photographer – he’d far rather you just called him a photographer. When you see , you’ll see why. Yes, he became famous photographing wars across several continents, but he’s shot all sorts of other things: famine (in Biafra), earthquakes (in Iran), poverty (in Northern England) and civil unrest (in Northern Ireland). He finds sadness and compassion everywhere.

His stark photos convey the human cost paid by the powerless poor

Yet you can see why that ‘war photographer’ tag has never left him. In the many wars he’s covered, his stark photos convey the human cost paid by the powerless poor. As his colleague William Shawcross said, he was frightening to be with because he took such mad risks, but the best thing about him was his gentleness. He never stopped caring about the people he photographed. His gaze was never blurred by the suffering he saw.

He was born in 1935, in London’s Finsbury Park – a diverse area today, but uniformly poor back then. He discovered photography during his National Service in the RAF, and got his big break in 1958, with his photos of a local gang called The Guvnors, which were published in The Observer.

From 1966 to 1984 he worked all over the world for The Sunday Times, in disaster zones as well as warzones, risking his life in search of news. Since then he’s shot a huge range of subjects, from the destruction of ancient architecture in Syria to the enduring beauty of the English landscape.

You don’t have to leave England to find a warDon McCullin

"This exhibition at Tate Britain will give people plenty of opportunity to pick and choose," he says, on the phone from his home in Somerset. "There are some unpleasant pictures in it but I can’t show my work without being honest about some of the appalling things I had to press the button on."

Even his peacetime photos convey a sense of trouble brewing. His new film for Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Four, Looking for England, is set in a land ostensibly at peace, yet there are signs of tension everywhere. In so many of these photographs, conflict still feels near. "I go where the drama is, and I didn’t have to get on an aeroplane to do it," he tells me. "You don’t have to leave England to find a war. There are social wars all over this country, in every city of this country."

McCullin fell in love with Somerset when he was evacuated there during the war. He eventually bought a house there. "I never forgot how beautiful it was," he says. "The area is steeped in history." He’s been photographing Somerset for thirty years. It’s still an important aspect of his work today.

I’m very sensitive about injustice. I’ve seen so much cruelty in my lifeDon McCullin

He was also evacuated to industrial Lancashire, which wasn’t quite so nice. "The people were quite spiteful to me," he recalls. "They really didn’t want us there." This painful experience also fed into his work – specifically in the bleak photos of urban Northern England which helped to make his name and, more generally, in his concern for the downtrodden and oppressed. "I’m very sensitive about injustice. I’ve seen so much cruelty in my life."

There was injustice aplenty in the Finsbury Park of his childhood. He shared a bedroom in a rented house with his brother, and his mum and dad. His dad, whom he adored, died when he was thirteen. "I left school at the age of fifteen, couldn’t read and write properly, suffered terribly from dyslexia, which got me a lot of hidings from schoolmasters," he recalls. "I have a problem with words and yet I have an amazing pair of eyes."

-

![]()

English landscapes

Mariella Frostrup interviews Don McCullin about the landscape surrounding his Somerset house.

His tough upbringing gave him a special empathy with his subjects. "I understood the violence, I understood the poverty."

I’d seen an awful lot of Hollywood war films, so I was looking for a bit of adventure, to be honestDon McCullin

However his greatest asset was his instinctive sense of what made a great photo. He calls himself a travelling inquisitor, "turning over stones and seeing if there’s any life underneath them, like you do as a child on a beach."

He’s never been so interested in the technicalities of photography. "All you have to do in photography is get the exposure right and then adjust your camera," he says. But that’s not all. "What you have to do is to adjust your mind, your emotions. That is the most important part."

Despite all his other work, his war photography will be best remembered. What made him seek out such perilous places? "I’d seen an awful lot of Hollywood war films, so I was looking for a bit of adventure, to be honest," he says, "but in the end that started to wear off and the fear kicked in. You saw what war did to other people."

He saw dead and dying children. He saw what shrapnel did to a human face. "When you saw all those things you calmed down. The adrenalin rush you got in the beginning started to go."

The famine in Biafra was the turning point. "It’s the cruelest death to see somebody starving." He realised war wasn’t his adventure – it was someone else’s tragedy. It’s this realisation which gives his photos their moral power. "You’ve got to start looking at this in a different way."

Covering so many wars has left him disillusioned with politicians, yet it has enhanced his faith in ordinary people. "What I’ve seen in my life is some of the greatest kindness from some of the poorest people in the world," he says. "The world is still full of decent human beings."

Don McCullin is at Tate Britain, London, from 5 February to 6 May 2019. Looking for England is on Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Four on 4 February at 9pm, then available on iPlayer.

Don McCullin: Looking for England

Inside Don McCullin's darkroom

Don McCullin is filmed in his darkroom for the first time in his 60 year career.

More Don McCullin

-

![]()

Looking for England

Travelogue following Don McCullin on a journey in search of his own nation.

-

![]()

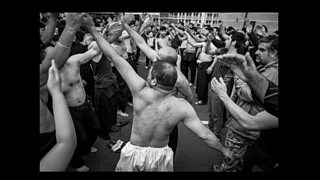

Ashura festival

Don McCullin photographs a procession for the day of Ashura in Bradford.

-

![]()

Desert Island Discs

The photographer talks to Roy Plomley about the eight records he'd take to a desert island.

Current exhibitions

-

![]()

Streetwise art

How Keith Haring made New York City his canvas.

-

![]()

London calling

How the capital inspired Vincent van Gogh.

-

![]()

The original emoji

Why The Scream is still an icon for today.

-

![]()

Da Vinci decoded

See the Renaissance master's drawings in twelve UK cities.

More photography from Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Arts

-

![]()

War and peace

The compassionate photography of Don McCullin.

-

![]()

Tish Murtha’s tender photos of deprivation in Britain.

-

![]()

Liam Wong's sci-fi-style images of Tokyo at night.

-

![]()

William Wegman's Polaroids of his loyal Weimaraners.

-

![]()

1940s New York through the lens of teenage Stanley Kubrick.

-

![]()

Behind-the-scenes photos of Johnny Cash's prison shows.

-

![]()

Hard-boiled photographs tell the history of crime in LA.

-

![]()

Rare photographs of the singer at the height of her career.