Bach A to Z

A series of personal reflections on J.S. Bach, his music and his world.

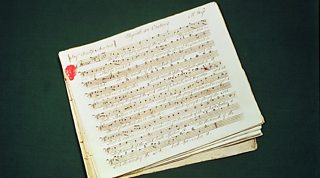

A is for Art of Fugue

Bach's 'The Art of the Fugue' is widely regarded as a defining work in the history of Western musical expression. It consists of 14 fugues and four canons and explores principles of counterpoint more fully than any other work before or since. The composer took a single great theme and subjected it to contrapuntal variations of immeasurable variety, poetry and imagination.

By the time of his death in 1750 publication, copper engraving as a form of publication was well advanced. Members of the family began handing pages to an unidentified, musically illiterate engraver. The logic and sequence of the music became increasingly haphazard. CPE Bach, the composer's 2nd son by Bach's 1st wife, (Maria Barbara), took over management of the score. Nonetheless a posthumous publication (1751) was hopelessly muddled. As a result the work suffered unjustified neglect.

Even today numbering of items and Bach's preferred instrumentation remains unresolved. In 1924 Wolfgang Græse, a Swiss student painstakingly prepared a logical running order with the fugues and canons apportioned to various groups of instruments. Its Leipzig premiere in 1927 caused great excitement on both sides of the Atlantic .

Subsequently however Græse's full orchestra scoring was sidelined in favour of versions for chamber orchestra or string quartet.

Sir Donald Francis Tovey believed the music was intended for keyboard. In 1932 he published an open score edition and one for keyboard. At the same time he completed the truncated final, 4-part fugue which, through Bach's worsening final illness, had been left unfinished at bar 239. Other transcriptions followed.

More recently keyboard performers have reasoned 'The Art of the Fugue' is best adapted for their own instrument; among them organist Helmut Walcha (1907-1991) harpsichordist Gustav Leonhardt (1928 - ), and pianist Tatiana Nikolayeva (1924-1993).

The imperishable content of this work remains inviolate but its shape and purpose continue to ignite controversy - truly a hallmark of great art.

Howard Smith

B is for B Minor Mass

It seems an extraordinary thought but Bach almost certainly never heard the B minor Mass complete. From what we know about other composers - Mozart and Haydn to take examples, works were only normally completed if there was a performance in sight. Bach seems to have put together the B minor Mass without a planned performance, working on the first part from scratch and then drawing in many of his other compositions to create a complete, perfect mass. He spent his last years and months tinkering with it and making it perfect and perhaps, during these final years of his life, it was his aim to put it together for posterity.

Bach wasn't used to hearing big performances of his works and certainly the performances we hear now are on a much larger scale. His other music is strictly for Church use and this strays right outside the boundaries.

From the time he died until about 1829, Bach was only known for his keyboard pieces as lots of people had copies of them. The large works - the Passions, Cantatas, the Mass, Magnificat and Christmas Oratorio were never performed. It's a big contrast to our attitude to Bach now, where there are dozens of recordings and performances. The average music lover is now fantastically more knowledgeable about Bach than Brahms ever was!

Sir Roger Norrington

C is for Cantatas

One almost can't believe that so many of the cantatas are so great. With most composers one is lucky to get a few pieces of music that one really loves, with Bach there's just so much.

Of all Bach's music, the cantatas are particularly rich in tunes and repeated motifs. When I was growing up, I associated religious music with school hymns, the most untuneful, dreary things, but many Bach cantatas are incredibly jolly and full of playful flourishes. They can be Vivaldi-esque in their lightness, but also incredibly sad. If you're feeling sad there's nothing better than listening to some sad music and Bach's music is about the most touching, melancholic and poignant that I've ever heard - he's absolutely perfect. It's through Bach's cantatas that, even though I don't believe in Christianity, Christian ideas come to seem most plausible. It's always striking to realise that there was a deeply religious message to them and that one is supposed to listen to a piece of music and feel closer to God. When I listen, I feel closer to the emotional range which God inhabits even for secular people - feelings of wonderment, feelings of humility, feelings of one's own fragility, death - all of these things come to mind.

Bach is often described as mathematical and people feel the rigour of the construction of the piece of music but there's also always a lot of emotion in it. I love that combination of having something that's cerebral and rational and at the same time very emotional, not just in music but in life in general. I would like to be a person that's a bit like a Bach cantata.

Alan de Botton

D is for Dance

I've choreographed three pieces of J. S. Bach. One was a project called 'Falling Downstairs' with Yo Yo Ma, based on the C major Cello Suite.

I studied the score of the suite and realised a couple of things. It's far simpler than I thought - there's very little material, just a descending scale and a couple of broken arpeggios. The whole piece is based on this. It's stunning to realise that such a simple idea is bent and stretched to make the most astonishing possible sound world.

The melody is often only in your mind, it's implied by what happens between different voices playing simultaneously. The polyphony implies a simpler tune that you're hard pressed to whistle because it's not there.

Like almost all Baroque music it's all based on Dance rhythms - the cello suites and the suites in the partitas are filled with Gigues, Sarabandes and Allemandes which spring from dance modes of the time and beg to be danced to.

Mark Morris

Bach is Dance music - even in pieces like the preludes and fugues there are minuets, bourees, gigues, passepieds - all the dances are there, you just have to recognise them.

Angela Hewitt

E is for Emotion

The first time that Bach moved me to tears was after the birth of our first daughter. I went home from hospital and listened to the B minor mass, that exuberant, magnificent choral opening which is followed by a fugue with the orchestra and the choir - a five part fugue. I know a bit about fugues and maths because I did music O level which meant composing a lot of Bach fugues and learning all about the relationships between tonic and dominant and the separations and inversions. The Kyrie is an exercise in mathematics, that's what a fugue is but its so much more than that, it's fluid and fluent and entirely natural.

Alan Rusbridger

People always talk about Bach as being the ultimate intellectual and mathematical composer. I'm not musically trained but I find Bach mentally stimulating, he excites me. I can almost feel my brain getting hotter as I listen to Bach. Emotionally he means a lot to me too - I find Bach consoling, it's almost like meditation. I'll stop the car and listen to something out of the Goldberg Variations or the Well Tempered Clavier - he takes me to a different place.

Andrew Marr

I like to listen to Bach non-vocal music as a sort of grounding - maybe Martha Argerich playing a partita. It's got this incredible intellect and emotion. The way that something as intellectual as a fugue weaves together and plays itself out is one of the most extraordinary things in the music and moves me every time.

Ian Bostridge

Everyone always goes on about Bach's mathematical genius and logic and if you listen to things like the Goldberg Variations or the Musical Offering that is perhaps principally what you are listening to, but I've always found him an intensely emotional composer. The story-telling of the human pain and story of Peter in the Passion has always moved me.

I went through my life with those pieces close to me. Sitting in a room at university, a friend put on the famous recording of the St Matthew Passion with Peter Pears as the Evangelist. In the section where Peter denies Christ, the Evangelist goes right to the top of his range on the words 'he went out and wept' - that really hit home and I realised that this man was a highly emotional composer - I've always clung to that.

Simon Russell Beale

F is for Faith

A lot of people think that if you listen to Bach - the quintessentially religious composer - you have to share his faith. Sometimes listening to, for example, the Magnificat or the St John Passion, you almost do need his faith, because when you have those soaring phrases and voices then you think 'what is Bach trying to do?'. Bach is trying to express musically almost the purity and the ascendancy of religious faith. I'm Jewish, I don't share that faith, can I appreciate that almost trying to touch the divine - can I appreciate it and not share his faith? The answer is yes, but with reservations, I'm happier listening to it when it's not in my first language and where I can listen to the sublime soaring of the human voice and not listen to what the words really mean.

Clearly when you're listening to the St Matthew Passion, the St John Passion or some of the Cantatas Bach is in a sense telling the Christian story - the story of Jesus, in Christian terms the son of God. This is something that as a Jew I cannot share. Some people would say that the whole Christian story is quite anti-Jewish. I personally don't believe that, I think Jesus himself was a Jew and that he taught Judaism. He taught a very un-orthodox sort of Judaism, but he taught Judaism. What was done with it later is a whole different question.

I don't have a problem with it, it just isn't mine - when I listen to Bach I'm not thinking that someone is telling a story that is directed against me, I don't think there is anti-Semitism there, remotely. All that Bach is doing is telling, in the most faithful and sublime of ways, the Christian story and he does it brilliantly - he is a great Christian composer. Bach was a good Christian soul who was expressly his Christianity in music that makes the heart sing - and it makes my Jewish heart sing.

Rabbi Julia Neuberger

G is for Goldberg Variations

Imagine a world which is also a river. Imagine a work of art made up of separate yet related elements which remain discrete but which, taken together, add up to more than the sum of their parts. Would not any artist be tempted to imitate such a work in homage to its creator?

Perhaps musicians can keep on top of the Goldberg Variations as it unfolds, but for most of us, I suspect, listening to it induces a curious sensation: we keep losing our way, forgetting how many variations have gone by and how many are therefore still to come; yet that, strangely, releases a response to the immediate moment which is just not possible with the more teleologically driven music of the centuries that followed. The mind drifts and, suddenly, we are at the end and the aria is returning, but now poignantly different because of what has gone before - or is it we who have been changed by listening?

Gabriel Josipovici

H is for Harpsichord vs Piano

On the harpsichord, you can't imitate the human voice by tapering a phrase- it must have disappointed people in Bach's time and I'm sure that Bach would have been thrilled to have had a keyboard instrument that could do this. The invention of the piano enabled this, and also produced a more powerful sound.

Bach gives you a wonderful technical grounding in how to play the keyboard. In his introduction to the 2 and 3 part inventions Bach explained that they were to develop playing clearly in 2 and then 3 voices, to develop a singing tone and to develop the independence of every finger. From a musical point of view, Bach helps learn about composition and structure - the development of themes through fugal treatments, phrasing, musical line - everything really. Bach gives such a good grounding to going on to later composers... you can hear a difference between pianists who have had that grounding.

Angela Hewitt

To me one of the greatest experiences of my youth was hearing the original Glenn Gould recording of the Goldberg Variations when I was at Cornell. When I discovered Bach I thought 'it's got to be on a harpsichord, anything else is a complete violation of history' and then I heard the Gould recording and said 'forget it'!

Steve Reich

I is for Improvisation

In Bach's time improvisation - making it up as you went along - played a far greater role in classical musicmaking than it does today. Solo singers and instrumentalists routinely devised melodic ornaments on the spot; the keyboard-players who accompanied them were expected to invent their own parts using just a bass-line and a set of coded instructions for the harmonies (the so-called 'figured bass'); and no virtuoso performer was worthy of the name unless he could extemporise at length with not a note of written music in front of him.

Yet even in this climate Bach's powers of improvisation were legendary. As an organist he was in the profession in which it counted most - organists were required to invent fantasias and fugues on hymn tunes as part of the church service - but there was no doubt that he was the master. There are reports of him making improvisations last half an hour, while in recitals he was apt to devise an entire sequence of pieces on a single theme, capping them all with a fugue.

His most famous feat of improvisation, however, came near the end of his life, when he visited the court of Frederick the Great and was given a 'royal theme' on which to extemporise a ricercar (or fugue) in three parts on the harpsichord. The theme was calculated to make his task as difficult as possible, but he managed it. When asked for a six-part fugue even Bach had to decline, but later, when he had written the original improvisation down, he made it the opening salvo in the sustained contrapuntal onslaught that is the Musical Offering.

Lindsay Kemp

J is for Jazz

J S Bach has always fascinated jazz musicians, ranging from Keith Jarrett's strictly classical interpretations to Jacques Loussier's "Play Bach" trio, which adds a dash of rhythm and improvisation. Many jazz players who had a classical apprenticeship retained their love for Bach's music. Consequently Bud Powell often included a Bach piece in his nightclub sets, such as his 1957 recording of "Bud on Bach", and the blind Welsh-born pianist Alec Templeton wrote his own swinging two-part invention, "Mr Bach Goes To Town". John Lewis frequently improvised fugues in the style of Bach with the Modern Jazz Quartet.

One of the most interesting Bach gems in jazz is by the Trinidad-born pianist Hazel Scott. Her version of the 2-part Invention in A Minor, from November 1940 shows her impeccable classical style, with J C Heard's drums bringing a little rhythm to her sparkling improvisations. Bach is also a source of quotations for those improvisers who cannot resist using a passing reference to something familiar. George Shearing has always been a master of this and the traditional Irish "Kerry Dance" on his Â鶹ԼÅÄ Jazz Legends CD has the "Kyrie" from the B Minor Mass woven into the theme, demonstrating Shearing's marvellous ability to make a verbal and musical pun at the same time. But it's not only pianists who have Bach in their hearts - Ron Carter's 1995 CD "Brandenburg Concerto" adds his pizzicato bass to a string orchestra for some exploratory improvisation, and drummer Max Roach paid tribute to Bach in a suite of pieces by his 1960s percussion ensemble. It seems Bach's influence is as all pervasive in jazz as it is in the classical world.

Alyn Shipton

K is for Kapellmeister

The word translates from German as 'chapel master', and refers to the most senior (and highly paid) musician at a court.

In Germany, during the 17th and 18th centuries, Kapelle could mean either the music staff (singers and organist) of a church or a court, however in the court context the usage expanded to take in operatic and orchestral activities if the court's music provision extended that far; a good example of this is the court at Dresden, which began with a Hofkapelle , founded in 1648; over time, an orchestra and opera were added, and the organisation (which still exists today) was renamed the Staatskapelle. By the 19 th century, secularisation had contributed to the term Kapellmeister being devalued and latterly used to denote musicians and music-making of inferior rank.

But in Bach's day the Kapellmeister held sway. He held the post at the court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen (1717-1723); his duties would have included hiring and firing personnel, rehearsing singers and instrumentalists, preparing music lists and composing. When Bach took up the position of Kantor , or director of music, at Leipzig in 1723, he was sensitive to an apparent loss of prestige in losing the Kapellmeister title; accordingly, he solicited - and was granted - the equivalent of an 'honorary' Kapellmeister title from Prince Leopold and his successor.

On his appointment as Kapellmeister at Cöthen, Bach received a salary of 33 Reichsthaler and 8 groschen per month, roughly £1375; he was the second-highest paid court official, and as a measure of his perceived worth (and, no doubt, negotiating skills), he received twice as much as his predecessor Augustin Stricker.

Graeme Kay

L is for Leipzig

For a long time, the city of Leipzig remained mysteriously hidden in the former German Democratic Republic; only in the last decade has the city becomes generally accessible. In Leipzig, Bach was working in a city with no royal or noble patronage. The motivation for its developed musical life can be found in the citizens themselves: for centuries, Leipzig has been an important commercial and educational centre, as shown in its trade fairs and ancient university. It had prosperous, ambitious inhabitants, who founded institutions for the performance of both sacred and secular music with amateurs and professionals. They also demanded church music of the highest quality.

Fortunately, the St Thomas' Church where Bach worked (and is buried) survived the bombing of the Second World War. You can still experience the great composer's music each Saturday afternoon and Sunday morning in its original setting. Attending these services is a reminder that Bach was working in the Lutheran heartland, not far from Wittenberg the cradle of the Lutheran Reformation.

Bach was responsible for the boys at the Thomasschule, and their voices provided music for the four major Leipzig churches. The school building, which contained the Bach family apartment, no longer stands. However, you can still experience the great composer's music each Saturday afternoon and Sunday morning in its original setting, in the church where he is buried.

But after church, do visit a coffee house to sample another Leipzig tradition!

Graham Dixon

M is for Musical Offering

I cannot listen to A Musical Offering without marvelling at the apparently limitless depth, range, and power of Bach's musical imagination. The theme of the work was given to him during a command performance for Frederick the Great in May of 1747, in front of an audience that included the best musicians in Germany as well as Bach's two eldest sons. Frederick had devised the theme - or instructed one of his composers to devise it - to be as resistant as possible to Bach's powers of improvisation, precisely because Frederick wanted to humiliate the man he called "Old Bach". Even more than he hated "counterpoint," Frederick loved to humiliate people, and he disliked Bach's music in particular. He said it "smells of the church".

To the shock especially of the composers in the audience that night, who knew when they heard it just how impossible Frederick's challenge was, Bach improvised a rigorous, very tight three-part fugue on Frederick's devilishly chromatic subject, which has ever since been called "The Royal Theme". Frederick, taken aback and no doubt rather annoyed, tried to get even by asking for a six -part fugue on the subject, which was too much even for Bach, who said he would have to pass and work that out on paper. So Frederick rescued some satisfaction from the evening, at least. But two months later, Bach threw the Royal Theme back in his Royal Face, with a sixteen-movement masterpiece that uses Frederick's fugue subject in every conceivable way and in ways inconceivable as well, in the most beautiful and affecting trio sonata he ever wrote, in ten strict and free canons - the most potent volley of canons in the history of music - and in a delicious wedding-cake of counterpoint that finishes off the work, the six-part fugue that Frederick had asked for.

Most music is better when you close your eyes, but this work positively requires it. No more impeccably consise, structurally graceful, and intensely contrapuntal work was ever written, even by the man himself.

No wonder it is so often forgotten that he wrote it on a theme that was meant to be too difficult for him.

James Gaines

N is for Numerology

The word "numerology" embraces a wide variety of esoteric techniques and interpretations and should never be used in association with Bach and his music. The boundaries in Bach's society were clearly drawn between what was acceptable, in terms of godliness, faith and pietism, and what overstepped the mark to become unacceptable superstition, mysticism and magic. Had Bach been a numerological practitioner he could not have taken the religious oath required of all pastors and school teachers in Saxony and thus would not have been appointed Thomaskantor.

Numbers were nevertheless an integral part of his world. Word and number conceits were popular with young ladies as well as useful for the more serious poet or orator who lacked inspiration. Among the much-published 18 th century techniques are the well-known anagram, chronogram and acrostic, together with the long-since forgotten paragram, which used any one of 30 or more different number alphabets to substitute letters with numbers. It is the number alphabet that connected Bach with numerology. In 1947 Friedrich Smend printed a paragram written by Bach's Leipzig librettist Picander. It uses the number alphabet A=1-Z=300. Giving no further evidence Smend then claimed that Bach embedded theological words in his compositions using an entirely different alphabet, A=1-Z=24. And people believed it.

Smend did not know what a paragram was. As a church historian, he had met a similar technique in Jewish cabbalism and falsely assumed that its use in the 1730s still had religious connotations. Smend was also drawn to the traditional interpretations of biblical number symbols. Again with no evidence to support his method, he presented detailed interpretations of selected numbers (of notes and bars) in Bach's scores. The lethal combination of symbolic interpretations and cabbalistic techniques that promised to unlock the secret depths of Bach's spiritual motivation in his greatest works proved irresistible. A fire was started in Bach studies that continues to smoulder and occasionally flare up today.

Knowing a technique and using a technique are two different things. Number alphabets, the paragram form and symbolic interpretations of numbers were common knowledge in Bach's day and society. But is there any documentary evidence to show that Bach used them? No.

Ruth Tatlow

O is for Oratorio

Bach's Christmas Oratorio is not just one composition, it's a series of reflections that takes us from Christmas through to Epiphany. Like so much of his great music, it takes us on a journey.

Quite early on, there are hints as to where it is all going to end up. Bach achieves continuity by playing around with a beautiful little chorale, repeating and reworking it, using it very slowly, solemnly, and joyfully. But perhaps the most extraordinary thing is what Bach does at the very end, taking the Passion Chorale which was so important in the St Matthew Passion and making it a Christmas Hymn as the final chorus in the Oratorio. The struggle, suffering and triumph that's embodied in the Passion is already present in the events of the Oratorio, as if what Christmas is really all about is the triumphant reinvention of the human race, which is the result of the life of Jesus. If you listen to the Christmas Oratorio as a whole, you hear an early reminder that this is the great Lord, the mighty King who is coming to struggle and battle. The incarnation is not just a sentimental story about a baby in a cradle, it's about a struggle. The person who is doing the struggle is celebrated in the bass aria early on, so when you get to the very end, you have already been given, in a sense, the whole story of which Christmas is the beginning. It's a story in which the greatest of lords, the most powerful of monarchs undertakes a struggle, through weakness and humility and becoming vulnerable. At the very end what's celebrated is the passion and the resurrection, all contained in these first events of Christmas, in the event of the incarnation - God becoming human flesh and blood in Jesus Christ.

Rowan Williams

P is for Passion

If I was only allowed to have one piece of Bach's and the desert island had really good hi-fi equipment it would be the St Matthew Passion - because of the wealth of contrast, drama and reflection and the great music that runs through this enormous work.'

Mark Elder

Drama is a centrally important part of Bach's music, even the shortest, smallest pieces have a powerfully dramatic quality and the Matthew Passion even more than the John Passion works with the plurality of voices arguing, pleading, occasionally coming together sometimes in real tension and real awkwardness and dissonance with each other.

One of the most significant aspects of the drama of this Passion is of course what it does to our perception of ourselves. The Matthew Passion is not written as a spectator sport, it's an event in which listeners are supposed to be involved. In early liturgical performaces the congregation would have joined in the chorales but even elsewhere there's a sense in which people speak for you in the Passions. Constantly the narrative is interrupted with those poetic meditations that some modern people find so difficult, where we have to identify ourselves with characters in the story, we have to take on our responsibility.

Rowan Williams

I got into the St. John Passion relatively recently having previously only rather reluctantly listened to Bach. Deborah Warner directed it at the ENO, and because she had directed me, I went to see it. The theatricality of the event sold me to it - it's a story that has long since bypassed its religious origins. If I was encouraging anyone to listen to it, I would say just listen without reading the story, because from the first group chorus, it feels like people singing on our behalf. The reason it works so well is that we can endow it with whatever meanings we want, because it is just the progress of the human soul to infinity through this blip called consciousness. It doesn't matter if there is redemption through Christ, there is redemption in the music itself, because while they sing, we are singing with them. The human potential is entirely explored, and one gets an enormous high - to me Bach is drugs.

Fiona Shaw

I'm about to stage the St. Matthew Passion but it's proving difficult working out how to provide a theatrical setting for it which still has the precision, tenderness and depth of the music. One feels frightened approaching a piece of that profundity and trying to make it into more of an operatic piece without tampering with it. Formally, it is immaculately structured with its chorales and arias but it's impossible to try and explain it emotionally. I hear it every Easter, and I just cry - in a perverse way, it is my yearly catharsis.

Katie Mitchell

Q is for Quotations

Schumann: 'Play conscientiously the fugues of good masters, above all those of Sebastian Bach. Let The Well-Tempered Clavier be your daily bread.Then you will certainly become a solid musician' ('Maxims for Â鶹ԼÅÄ and Life' Haus und Lebensregdn, 1848)

Hector Berlioz: 'There is one God - Bach - and Mendelssohn is his prophet'

Paul Hindemith: 'I don't know how, with no vibrato, Bach could have so many sons.'

A village organist on finding Bach playing his organ: 'This can only be the devil or Bach himself'.

A member of the Arnstadt Council in 1705: 'If Bach continues to play in this way, the organ will be ruined in two years, or most of the congregation will be deaf.'

Goethe: 'It is as though eternal harmony were conversing with itself, as it may have happened in God's bosom shortly before He created the world.'

Beethoven: 'Not brook but sea should be his name'.

Schubert: 'Johann Sebastian Bach has done everything completely, he was a man through and through.'

George Bernard Shaw: 'Bach belongs not to the past, but to the future - perhaps the near future.'

Debussy: 'A benevolent god, to whom musicians should offer a prayer before setting to work so that they may be preserved from mediocrity'.

Thomas Beecham: 'Too much counterpoint - and what is worse, Protestant counterpoint'.

Chopin: 'Bach is like an astronomer who, with the help of ciphers, finds the most wonderful stars...Beethoven embraced the universe with the power of his spirit...I do not climb so high. A long time ago I decided that my universe will be the soul and heart of man.'

Schumann: 'Music owes as much to Bach as religion to its founder'.

Saint-Saens: 'What gives Sebastian Bach and Mozart a place apart is that these two great expressive composers never sacrificed form to expression. As high as their expresson may soar, their musical form remains supreme and all-sufficient.'

Michael Torke: 'Why waste money on psychotherapy when you can listen to the B Minor Mass?'

Nina Simone: 'Once I understood Bach's music, I wanted to be a concert pianist. Bach made me dedicate my life to music.'

Brahms: 'Study Bach, there you will find everything'.

Gounod: 'If all the music written since Bach's time should be lost, it could be reconstructed on the foundation which Bach laid'.

Mahler: 'In Bach the vital cells of music are united as the world is in God.'

Wagner: '...the most stupendous miracle in all music!'

Douglas Adams: 'I don't think a greater genius has walked the earth. Of the 3 great composers Mozart tells us what it's like to be human, Beethoven tells us what it's like to be Beethoven and Bach tells us what it's like to be the universe.'

R is for Religion

Before I realised that I was atheist I used to say that Bach was God's favourite composer - and that still might be true even though I don't believe it. Obviously Bach wasn't the first composer and didn't invent opera or religious music, but he was obviously the greatest one, unless there's a missing one!

Mark Morris

I'm not religious at all, I'm a flinty atheist - I think Bach does for me some of the things which religion does for other people. Bach draws me out of myself and makes me more sensitive to what's going on in my life at the time. I can find him very disturbing, and moving. To say Bach is a great intellectual composer seems to me to miss more than half of the point.

Andrew Marr

A lot of people think that if you listen to Bach - the quintessentially religious composer - you have to share his faith. Sometimes listening to, for example, the Magnificat or the St John Passion, you almost do need his faith, because when you have those soaring phrases and voices then you think 'what is Bach trying to do' - Bach is trying to express musically almost the purity and the ascendancy of religious faith. I'm Jewish, I don't share that faith, can I appreciate that almost trying to touch the divine - can I appreciate it and not share his faith? The answer is yes, but with reservations. I'm happier listening to it when it's not in my first language and where I can listen to the sublime soaring of the human voice and not listen to what the words really mean.

Julia Neuberger

It's very difficult to know how you would characterise Bach as a religious composer -he's not just a composer who sets religious texts, he's a composer who sees all his music as a kind of spiritual exercise. Although performers and listeners may not share his confessional convictions, its difficult to listen to Bach without that sense that you are being invited to change your life... something in Bach prompts you to re-evaluate who you are, that re-evaluation of your feelings and your thoughts.

Rowan Williams

S is for Space

I first heard the Bach solo violin sonatas and partitas when I was 18 and a student. For some reason I thought of space - the planets, the solar system and way way beyond. Then I heard that when the Voyager 1 satellite went up into space, it took a package containing representative illustrations of the finest human achievements, including Glenn Gould playing Bach. So the NASA scientists agreed with me that Bach was the sound that we should send out into the solar system and now he's somewhere out beyond Alpha Centauri!

Although it sounds slightly pretentious and quasi philosophical I think it's something to do with the fact that Bach's music sums up music - it's music about music. He tries to explore what can be done with the medium he works with, taking the violin, cello and keyboard to their outer limits. I think he's probably on the verge of trying to discover what we are capable of spiritually in his cantatas and great choral pieces.

Armando Ianucci

Bach is for me an architect in sound. He has invented a different sense of place through music and both my spirit and mind are shifted as I have tried to learn how he works. It must be the choreographer in me that identifies with the idea of music and shape. The opening theme of the Art of Fugue creates a complete minimal and original space each time I listen to it, and it is also the beginning of an immense story about to be told. Those few notes, points on an architectural plan, are later imbedded divided, multiplied, reordered, quickened and drawn out. Each mathematical shape releases beauty - an immense and fabulous idea. I listen and learn and sadly do not reach that same clarity, but I am made happy by imagining my potential improvement. I need to create a space and only fill it with completely necessary moves.

I have been re-listening to the Musical Offering having read the book 'The Evening of the Palace of Reason ' by James Gaines, which has alternate chapters about Bach and Frederick the Great. The last chapter focuses on the king giving the composer a theme and asking for an immediate 3 part fugue. Bach sits down, and in my imagination displays the virtuosity of a fabulous contemporary jazz musician. I begin to listen to the Musical Offering, intending to unravel its structural complexities, but my thinking brain and my imagining brain plait together every time. I am no longer in an isolated thought place or an isolated emotional one, I am combined and while I listen I am in a space of articulate beauty. My ears and a truly developed musical understanding are not polished enough to keep concentration throughout, but my creative energy is fired up. In Webern's orchestral transposition of the 6 part fugue that closes the Musical Offering, each entry is made clear by the instruments of the orchestra. The original space is not only filled with fugal structure but also the colour, textures and character of individual instruments. My sense of architectural space is made large and vividly alive - it is three dimensional music to walk about in.

Siobhan Davies, Choreographer

T is for Temperament

The physics of sound can't cope with the demands of Western music. If you do it mathematically, a keyboard instrument will only be playable in a few keys, creating an extraordinarily rich, warm sonority. But reach further into the twelve notes of our scale and the 12 major/minor keys, and things go horribly awry. For example, tune a beautifully pure-sounding third, from C up to E, another from E to G#, and finally G# to B#. B# looks like C on your piano - but it isn't, and these three pure thirds equal a horrendously flat 'octave'. To put it another way, if you go round what's called a circle of fifths, going up five notes each time (CGDAEBF# etc...), the C you eventually get back to will be horrendously out of the tune with the one from which you started!

When composers stuck to simple keys rather than exploring further, they selected a tuning system in which made a few keys sound great - and it's indeed a wonderful experience to hear chords in such a 'mean-tone temperament'. Mind you, a semitone scale can sound quite bizarre.

As music ventured further, into more remote keys, musicians compromised with tunings in which everything was just about playable, but some keys sounded relatively pure while others sound doleful, aggressive, snarling... Bach certainly knew about so-called 'equal temperament' where all keys are indistinguishable from each other. However, there's evidence that the 'Well-Tempered Clavier' was intended for one of the 'compromise' tunings (or 'temperaments'). In Book I at least, you can hear the Preludes matching the characters of the keys. The first Prelude has slow, sustained harmony in sonorous C major while the third skitters around a rather twitchy C#.

But you gain something and lose something else... With the way we normally tune keyboard instruments nowadays, we make all our semitones exactly the same - it's called 'equal temperament'. We can play equally in any key - but we have lost kaleidoscope of colour in which every key had a different character, and when to change key was not simply to change pitch.

George Pratt & Graham Dixon

U is for Ubung

Ãœbung is the German word for 'practice'. In the Bach context it occurs in the title of collections of keyboard music written between 1726 and 1741, and labelled the 'Clavier-Ãœbung'. By using the term in this way, Bach was emulating his predecessor as Kantor of Leipzig, Johann Kuhnau (1660-1722).

In Bach's catalogue, the Clavier-Ãœbung Part I (1726-31) consists of the six partitas BWV 825-30; Part II (1735) contains the Italian Concerto BWV 971 and the Ouverture in the French style BWV 831; Part III (1739) contains organ music (BWV 669-89 and 802-5): the collection is framed by the 'St Anne' Prelude and Fugue in E flat (BWV 552), and includes 'various preludes on the catechism and other hymns for the organ'; Part IV (1741) is the Goldberg Variations.

In the contect of 'practice', Bach could of be overtly didactic in the preparation and publication of his music. The seminal Orgel-Büchlein collection of chorale preludes was dedicated 'to a beginning organist in how to set a chorale in all kinds of ways, and at the same time to be practised in the study of pedalling.' In terms of learning keyboard technique, there is a distinct pedagogical progression in Bach's music which would have guided Bach's son Wilhelm Friedemann through the Clavier-Büchlein, the Inventions and Sinfonias, the Well-tempered Clavier and the six Organ Sonatas.

Interestingly, the German version of 'Practice makes perfect' is 'Ãœbung macht den Meister' (Practice makes the master). The notion of 'practice' is interesting in the context of a catalogue of free-standing keyboard works of the superb quality represented in the Clavier-Ãœbung; in German the word also has a sense of 'the exercise of ...'; this is consistent with an interpretation of the Clavier-Ãœbung as a body of work representing a summation of Bach's musical and spiritual thinking on the liturgy, and the musical means employed to realise it.

Graeme Kay

V is for Veit Bach

Veit Bach (d. before 1578) was Johann Sebastian Bach's great-great-grandfather and the founder of the Bachs as a musical dynasty; he is often confused with another Veit (d 1619) of whom little is known and who may have been a son or nephew. Though a baker by profession, Veit senior played the cittern (a Renaissance-period instrument combining elements of the lyre and guitar, and played by means of a quill plectrum). The Bach histories are specific that Veit marked 'the beginning of music in his descendants'.

Veit was from Wechmar, a town which lies between Gotha and Arnstadt in the Central German region of Thuringia . The rise and subsequent decline of the Bach family is intimately bound up with the demographics and political landscape of this part of the country. Though composed of a patchwork of small courts, and riven with political splits, the region was united by its Lutheran faith; coincidentally, the absence of any major city or court with its attendant opera company and orchestra meant that starry talents were unlikely to come in from outside - yet the requirements of civic and princely prestige created a fertile market for skilled, practical musicians.

Given that musicians tended to learn from each other, such conditions were more likely than not to encourage the emergence of musical dynasties, as musical families intermarried and proliferated: in Thuringia, music revolved round not just the Bachs, but also the families of Hoffmann, Lämmerhirt and Wilcke. Johann Sebastian's mother was a Lämmerhirt, his first wife Maria Barbara, a Bach, and his second wife Anna Magdalena, a Wilcke.

Johann Sebastian lineage through to Veit is through his father Johann Ambrosius (1645-1695), organist, violinist, singer, percussionist and court trumpeter in Erfurt and Eisenach; through his grandfather Christoph (1613-61), court and town musician in Weimar, Erfurt and Arnstadt; and through his great-grandfather Johann [Hans] (1550-1626), baker, carpet-maker, and latterly, professional minstrel and fiddler. Records indicate that the musical dynasty spawned by Veit Bach came to number 53 organists, Kantors and town musicians spanning three centuries.

Graeme Kay

W is for Walking

Although Bach never left Germany , there were many occasions in his life when he undertook long journeys across the country. It is generally assumed that these journeys were made on foot, as he was never particularly wealthy, although it is possible that he may have negotiated a lift on occasions! In Bach's time, of course, long-distance walking between towns and cities was much more an aspect of everyday life than it is now; routes would have been well-trodden by traders and food and lodging would have been readily available in the towns and villages along the way.

Bach's first major journey on foot probably took place in March 1700, when he travelled to Luneburg from Ohrdruf (a distance of nearly 200 miles), just before his fifteenth birthday, to take up a free educational place at the Michael isschule. In Luneburg he would have been able to hear the playing of the great organist Georg Bohm, and the prospect of listening to and learning from other more experienced musicians seems to have been the main motivating force behind most of his subsequent journeys. During his three years at Luneburg , he is known to have walked to Hamburg (30 miles away) more than once in order to hear and meet the organist Johann Adam Reincken . Returning from one such visit, it is said that he had the good fortune to find a Danish ducat inside the mouth of a fish that had just been discarded from a window - thus providing valuable funds for future travels!

The longest walk of Bach's life, however, was his journey from Arnstadt (in Thuringia) to Lubeck (on the Baltic coast) to hear the very famous organist Dietrich Buxtehude . This trip was made in the winter of 1705 and totals some 260 miles, a feat all the more remarkable for the fact that the return journey (made in February 1706) would have seen Bach carrying, and somehow keeping dry, several manuscript copies he had made of Buxtehude's music! The exact route Bach took is not known, though it seems reasonable to suppose that he might have travelled through Gotha, Muhlhausen (where his next appointment was to be), Northeim, Seesen, Braunschweig, Luneburg (where he might perhaps have found free accommodation?) and then via the well-worn salt route to Lubeck. Although there is disappointingly little evidence of this journey, we must remember that Bach was merely another 20-year-old wanderer at the time; none of the people he would have met along the way would have had any idea of his future greatness!

Peter Dyke

Y is for Youth

In reading about Bach and looking at his portrait I see a completely different Bach from how I imagine him. The picture I have in my mind of him is like that in the Bach house in Eisenach - he is a young person, 26 or 27 - intelligent, smiling, beautifully dressed, ready to conquer the world and become somebody important.

Although I like the last music that he wrote, Bach is always a young person for me, someone who is energetic in his music making...who is flesh and blood, not an evangelist but a normal believer, as everybody was a believer at that time. He is a craftsman in every respect and a great virtuoso. I would have loved to have drunk a glass of wine with him.

Bach looks disappointed in the Sofia portrait that you find in Leipzig. The world of Leipzig was a little too small and wasn't nice to him although he gave it something that no other composer in musical history ever could.

Ton Koopman

Z is for Zimmermann Coffee House

Coffee drinking was all the rage in Bach's Leipzig. If you read the text of his Coffee Cantata (BWV 211) you will find out that - in the minds of the older generation - frequenting a coffee house has many of the overtones that clubbing might have these days. Coffee had come down in price, and all classes of society could now enjoy the exotic drink. Unlike the main protagonist in the cantata, Bach was no killjoy when it came to drinking coffee. From 1729 he directed performances every Friday evening at the venue in the smart Katherinenstrasse near the central market square. Much of Bach's chamber and orchestral music, including the harpsichord concertos, was written for performance there.

Much has been written about the destruction of Dresden, but nearby Leipzig also suffered badly in the Second World War. This included the destruction of the original Zimmermann Coffee House. For this reason we cannot relive the experience of hearing the music in the original venue. However, Leipzig has another Coffee House, Zum Arabischen Coffe Baum (the Arabian Coffee Tree), which dates from shortly before Bach's arrival in Leipzig , being founded in 1720. It is a great place where you can still enjoy the coffee element of the Zimmermann experience. It does have musical associations, since Schumann was an extremely regular customer. Well, we don't know how loyal Bach was to Zimmermann's, but it is just possible that he slipped in there (but not on a Friday evening of course!).

Graham Dixon

The World of Baroque

-

![]()

Find out more about the Baroque Spring season.

-

![]()

Listen to programmes about the major baroque composers and their music.

-

![]()

Discover how the principle of contrast defined a new musical era.

-

![]()

Visual guides to the lives of Bach, Handel, Purcell and Vivaldi.