The technology that captured The Green Planet

By Rupert Barrington, Series Producer for The Green Planet

A new perspective on plants through innovation

For The Green Planet we wanted to find new ways to film plants, both in timelapse, and in real time, and from the scale of the landscape right down to subjects of stunning beauty just fractions of a millimetre in size.

we wanted to find new ways to film plants

In other areas of film-making, technological developments over the years have allowed us to move the camera in ever more ambitious ways, to create dramatic tracking and aerial shots. Timelapse filming technology, on the other hand, has developed very little. The Green Planet team’s ambition was to build and pioneer new technology that could allow our cameras to fly into the plant’s world, while filming in timelapse. This would allow us to see the world on their timescale and from their perspective, and reveal that plants act more like animals than we previously thought.

Robotic timelapse camera rigs

One of our producers, Paul Williams, discovered that an ex-military engineer in the USA, Chris Field, had spent a decade building robotics rigs in his basement as a hobby. He had created systems to allow the camera to move freely around a plant, while filming it in timelapse. We formed a partnership with Chris for The Green Planet. First, he built robotics rigs for us that he installed in the UK studio of the world’s leading plant timelapse photographer, Tim Shepherd.

Chris Field, had spent a decade building robotics rigs in his basement as a hobby

Then he designed completely new rigs, nicknamed Triffids, that we could take into the field, to allow the camera to travel into the plant’s world and film in timelapse in all sorts of environments, from desert to jungle. Finally, he designed a miniature version of this system to allow us to film the wonderful detail of the plant world.

With these rigs we were able to take the viewer into the plant’s world, and capture the extraordinary dynamism of their behaviour, from huge battles for space in a Brazilian wetland, tracking across the forest floor to follow a column of leaf-cutter ants in timelapse, to capturing the hunting behaviour of a parasitic plant on an English riverbank.

Finally Chris built units to house timelapse cameras that were powered by the sun. This enabled us to leave timelapse cameras in place, slowly recording the changing world, for months or even years.

New lenses

We employed two brand new lens systems on The Green Planet. Paul spotted, on the internet, a new kind of probe lens that was being developed. We snapped up several of these which, among other uses, were perfect for our field robotics system, The Triffid. The length and small lens size allowed us to move them close to the surfaces of plants and through tiny gaps. The other lens system was a series of supermacro lenses that allowed us to capture the wonderful detail of the plant world with spectacular clarity.

First person fly-throughs

a new way to capture aerial footage

We took drones to many remote plant habitats around the world, to capture beautiful and dramatic landscapes. But here again we wanted to find a new way to capture aerial footage, that would immerse the viewer in the plant world in a way that has not been possible before. We were all excited by the potential of tiny, First Person View drones, also called Stunt or Racing Drones, which have been developed for competitions. A highly skilled pilot, using a headset which allows them to see the viewpoint of the drone, can perform remarkable feats of high speed, aerial acrobatics through complex obstacle courses. We wondered if they could give us a new way to explore the complex space of the plant world. Producer Rosie Thomas and Assistant Producer Ali Tones set up the first shoot in the USA and the images that came back were stunning. The skills of experienced pilots turned out to be perfectly suited to flying through the obstacle courses of the green world. Across the series they have captured unique and dynamic views of different plant worlds; skimming over forest floors, flying through tangles of branches and spinning around a tumbling waterfall.

Capturing cinematic microscopic beauty

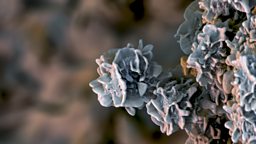

We also wanted to find new ways to film plants in close up and capture the beauty hidden on a miniature scale - from the textures of a cactus spine to the microscopic breathing holes on every leaf surface. Once again the key was to find ways to keep the camera on the move, even at this scale.

Once again the key was to find ways to keep the camera on the move, even at this scale.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) produces ultra-high-resolution, still images for scientific study. However, we worked with an expert in Germany, who has designed a system incorporating multiple axes, that allows him to capture not just video images in SEM, but to effectively fly the camera around subjects of fractions of millimetres.

flying into the world of plants right down to an extraordinarily small scale

We also worked with a special microscope, this one using light, not electrons, to create the image. It allowed us to zoom in from a wide shot to a huge close up, in a single shot, holding focus all the way, while also moving around the subject. This system provided some startling imagery for the series and, like the scanning electron microscope, allowed us to continue the imagery of flying into the world of plants right down to an extraordinarily small scale.