Image: A Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Emitron camera films the Olympic Opening Ceremony in London, 1948.

Early experiments: the Berlin Games of 1936

The London 1948 Olympic Games were not the first to be televised. Between 1 and 16 August 1936, whilst the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ was assessing the best way of operating a full television service to be seen in people's homes, Germany was finding out what television could do by covering the Berlin 1936 Olympic Games.

To televise the event, the German Post Office deployed two different operating systems. Stadium events were covered by an all-electronic system. Others were broadcast using a technique which used film, developed almost instantaneously, and shown a few minutes after the actual event had taken place. The result was distributed by cable to selected party officials and to the competitors' living accommodation.

The general public could not purchase television receivers, but 25 television viewing theatres or 'parlours' were set up in the greater Berlin area for viewing by local people.

A reporter from The New York Times described watching the 4 x 100 metres men's relay on one of the public TV receivers.

It was evident that the boys were running fast, but Jesse Owens looked awful and Frank Wykoff's legs wobbled. The stadiums' spectators in the background sort of melted together, and the whole scene shook like a jelly... the eye strain was considerable and many didn't stay for the remainder of the afternoon's events.

By the time the Berlin 1936 Olympic Games were over, initial Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Television Service trials at Alexandra Palace, were complete. This allowed production staff to become familiar with the different type of operating systems that had been chosen. One was a mechanical system invented by the Scottish scientist, John Logie Baird, the other was the Marconi-EMI all electronic system.

Initially, demonstration of British television was to people visiting the annual Radiolympia exhibition (the British consumer electronics show of its day) between 26 August and 5 September 1936. Electronic 'Emitron' cameras not only covered programmes made in studios, but were also taken outside to show viewers scenes of London from Alexandra Park.

After completion of the demonstrations, the service was shut down to allow final installation work to be carried out. A thorough evaluation of the Baird and Marconi-EMI systems could then take place in the context of a regular service, free-to-air, to domestic viewers. This was the first service of its kind in the world, starting on 2 November 1936, operated by the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ.

It was announced on 2 January 1937 that the Marconi-EMI system, which provided programmes in higher definition than the Baird counterpart, had been selected for use by the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ. The Baird system was dropped.

One of the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ's first actions, once the EMI system had been fully adopted, was to order a mobile outside broadcast unit that it would use to televise the Coronation of King George VI on 12 May 1937. The unit was equipped with three cameras and it covered the Coronation procession as it went through Apsley Gate at Hyde Park Corner.

Good close-up pictures of the King were obtained. Six months later the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ ordered a second OB unit that was delivered in May 1938 (fitted with the more sensitive Super Emitron cameras) to fulfil the desire of the viewing public to see more outside broadcasts.

Then the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Television Service closed down completely in anticipation of the outbreak of the Second World War, and wasn't to re-open for another seven years.

Notwithstanding the missing war years, the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ originated some 500 outside broadcasts before the London 1948 Olympic Games. They covered sport of all types, visits to funfairs, hobbyists displaying their skills, model boat and aircraft displays, fashion shows, Remembrance Day services, visits to the London Zoo, the film studios at Elstree, film premieres, the Chelsea Flower Show, plays from West End theatres. You name a genre, and the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ probably covered it as an OB!

After World War II

After the war the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ asked the EMI company to start developing a more sensitive camera tube, which became known as the CPS (Cathode Potential Stabilised) Emitron camera. Two prototype cameras were built and brought into operation to help cover the wedding of Princess Elizabeth (who was to become Queen Elizabeth II less than five years later) from outside Westminster Abbey on 20 November 1947.

A fortnight later the cameras covered the visit of the King, Queen and Princess Margaret to Broadcasting House for a special performance of ITMA (It's That Man Again), a war-time radio comedy, designed to bolster the morale of the nation.

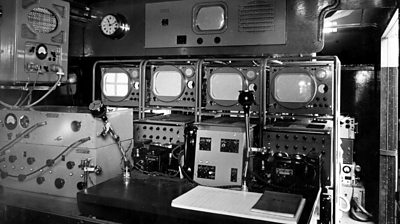

As the trials with the prototypes went reasonably well, the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ placed an order with EMI, to produce a completely new type of OB unit for the London 1948 Olympic Games. In addition to incorporating the new cameras, the new unit was designed to allow all the members of the operational and production crew to be seated which had not been possible in the pre-war OB vans.

Ian Orr-Ewing (above right), Head of Television Outside Broadcasts, was thrilled with the new equipment:

It's no secret that outside broadcasting in the past has been carried out under great difficulty and with very cumbersome equipment. The new CPS Emitron camera is extremely sensitive and can produce good pictures in light far too dim for cine cameras.

A shop window for television

In deciding to cover the London 1948 Olympic Games by television, the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ felt that, as it provided the only regular daily television service outside North America, it should put on the greatest display of their competence in television operations and production.

The London 1948 Olympic Games would therefore be a 'shop window' for the fledgling British television industry.

In order to do this, the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ converted the old Palace of Arts (in Wembley, west London), built for the British Empire Exhibition of 1924, into the International Broadcasting Centre. The site was close to the main Olympic venues, the Empire Stadium (known later as football's Wembley Stadium) and the Empire Pool (also located in Wembley).

International Broadcasting Centre

The International Broadcasting Centre occupied 35,000 square feet of floor space. It housed 16 radio studios, 20 disc-recording channels, and the central radio control room. There was accommodation and communications for reporters, and two television control rooms. It was the home to 200 reporters and 350 engineers, and there were 134 visiting reporters from 60 radio organisations, representing 28 different countries.

The Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ deployed 146 reporters to supply reports to its range of services in 41 languages. It could handle 38 simultaneous broadcasts from 21 different locations. There were 364 broadcasts a day, 114 were live and 250 were recorded, mainly because of time differences around the world. The broadcasts lasted between fifteen minutes and four hours.

Three pre-war television cameras were located in the Empire Stadium, two covering the action, and one for captions and photo-finish photographs. In the Empire Pool two of the new CPS Emitron cameras covered events in the pool, and one was placed in a specially built interview studio. The selected pictures from each OB unit were sent by cable to a Master Control Room, specially built in the Broadcasting Centre, where Ian Orr-Ewing, selected the source of the picture, Stadium or Pool.

The decision was based on the comparative programme values of the events taking place at the time. His selection was carried by video and sound cables via Broadcasting House to the transmitter at Alexandra Palace. To ensure continuity of the service in case of a breakdown of the cable route, there was a standby mobile outside broadcast VHF link direct from the Broadcasting Centre to Alexandra Palace. This was only brought into use on one or two occasions.

What did the viewers see?

How much action did the viewer see? Approximately 100,000 households had television sets at the time, and they saw some 68.5 hours of live coverage. That is roughly 5 hours per day. What did these viewers see? Take the 31 July. Between 11.00 am and mid-day, viewers were shown live coverage of the men's long jump and pole vaulting qualifying events, water polo and the men's springboard diving. Then, between 2.15 and 4.00 pm, viewers could see from the Empire Stadium the men's 100 and 800 metres semi-finals, and the women's 400 and 100 metres finals.

From the Empire Pool they could see the women's springboard diving and 200 metres breaststroke, and the men's water polo. And between 5.00 and 6.00 pm there was the finish of the 50,000 metres walk. To round off the day's viewing at 8.00 pm, with quite low light levels in the Empire Pool, there was coverage of the 100 metres freestyle semi-finals for women, the 400 metres freestyle semi-finals for men, as well as water polo.

An experimental tele-recording (made by pointing a film camera at a flat TV monitor), of the opening ceremony was made. It shows very good picture quality, particularly when the weather was bright. Viewers would have watched the 'flicker free' pictures on receivers with an average picture size of around 10 by 8 inches, although curtains in the room might have to be pulled to ensure the picture was bright enough!

It was generally accepted that the coverage of the London 1948 Olympic Games heightened the profile of the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Television Service, and its Outside Broadcasts department. Lessons were learnt, and much of that experience put to good use for the highly successful transmission of the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on 2 June 1953, when Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Television's competence was applauded the world over by public and television industry alike.

Since his retirement as Head of Technology for ITV in 1995, Norman Green has become an authority on the life and work of key television engineers. Norman’s long career in television engineering has covered most technological developments of the past 50 years - 625 lines, colour, Teletext, HD and digital delivery. He is a fellow of the Royal Television Society.

The Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ and the 1948 Olympic Games

-

The Birth of TV: London 1948 Olympics

The '100 Voices that Made the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ' project unearth unique oral histories from the team who made the biggest outside broadcast ever attempted. -

Broadcasting the 1948 Games

How the coverage looked, sounded and how it was promoted by the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ in 1948. -

Staging the 1948 Olympic Games

Senior television engineer Norman Green recalls the preparation for the biggest outside broadcast yet attempted -

Working on the London 1948 Olympic Games

Producers, camera operators, and others recall how they coped with a tiny budget and pre-war equipment.