Few events in the UK dominate the sporting landscape like Wimbledon. Matches played every July at the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, known worldwide as simply "Wimbledon", have been faithfully reported by the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ in an unbroken partnership with the All England Club for 96 years. It's a hugely important relationship for the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ - the longest broadcasting sports rights contract in the world.

Richard Haynes, Professor of Media Sport in the Communications, Media and Culture Division of Stirling University, has written a book about those early days Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Sport in Black and White. He notes:

"Wimbledon has always been near the top of the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ's 'must have' events...Wimbledon had obviously existed for several decades before radio, but broadcasting brought it to a wider audience. For this reason, the All England Club have always found free-to-air broadcasting the best possible promotion of Wimbledon's status in the sporting calendar. Like the Boat Race, it was part of a national ritual of sporting events that the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ regularly broadcast."

Early days

The first attempt at covering the event was a logistical miracle. GPO lines ran from Broadcasting House in central London to Wimbledon at great expense and disruption. The control point was housed in a second-hand telephone box bought for Β£5. Permission was granted to build a small commentary box in the corner of Centre Court, and its cramped space and tight access up some ladders remained for many years.

The commentator was Captain Henry Blythe Thornhill "Teddy" Wakelam. As well as being a rugby union player, Wakelam had umpired at Wimbledon in the early 1920s, so when the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ enquired about coverage, Major Larcombe of the All England Club suggested Wakelam's name. By then he had commentated on rugby and football that year, so was a natural choice. The Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ also appointed R. H. Brand at the insistence of the Club Colonel; as well as being a member of Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ staff he was a well-known tennis player, and they remained for a decade.

Wakelam recalled how his commentary of one of the men's semi-finals was abruptly interrupted when as a Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ announcer changed the programme to the "Girls' Friendly Society Concert" at the Royal Albert Hall. For Wakelam, apart from the heat and personal discomfort, he found commentating on tennis much easier than any other sport. His identification of players was not an issue, and his view was unhindered and incredibly close to the action.

While they did long stints on the radio, both Wakelam and Brand continued their roles as umpires. There obviously seemed no conflict of interest, and having an expert in the sport in the commentary box clearly suited the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ.

Television arrives

The first televised match took place on the opening day in 1937 between Bunny Austin and George Lyttleton Rogers, but broadcast for only 25 minutes. The cameras were connected by a cable to a small unit located in a car park, then transmitted to the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ at Alexandra Palace.

One of the post war pioneers as coverage expanded was Ron Chown. He had joined the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ before being called up during the Second World War, and re-joined in TV Outside Broadcasts. He worked on those early broadcasts in the late 40s and early 50s, when there were few rules about how to televise sporting events. Sometimes practicalities even dictated how traditions began. Chown remembers:

"We had only one OB unit and three cameras and Centre Court even then had a small roof, but it was held up by pillars. They got in the way, so we couldn’t film or track side-on, we had to film from one end."

Chown remembers it as THE Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ event to work on:

"Everything was turned out on from the engineering side, but with only one OB unit you couldn't enjoy the sport, you had to concentrate on getting the levels and the light balance in the cameras right. If you didn't, you got the sack!"

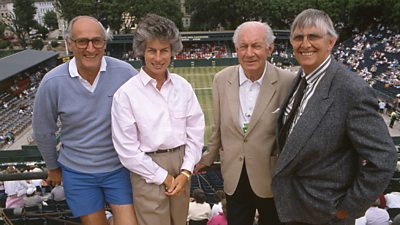

Dan and Max

Two contrasting voices dominated Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ coverage over the next 40 years, one on TV and one on radio, both developing styles that perfectly suited their respective mediums. Dan Maskell had been a ball boy at Wimbledon, then a decent professional player and coach. After the War ended he had joined the All England Club, coaching members of the Royal family amongst others. Maskell, who first went to Wimbledon in 1924, claimed to have attended every day of play at Wimbledon from 1929 onwards.

Joining the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ in 1949, his first couple of years were alongside radio's Max Robertson before moving to TV. From then until his last Men's final in 1991 he never missed a day, and his style became endearing to millions. Only speaking between points, and sometimes not even then, his trademark catchphrases of "Oh I say!" and "A dream of a volley" entered tennis folklore. "All one tries to do," said Maskell deprecatingly of his style, "is to inform the viewer of things that add to their appreciation of the match."

On radio Max Robertson ruled the commentary roost from 1946-1986 with a rather different style. Born in India, he worked as a teacher then for the Australian Broadcasting Commission, doing his first tennis final in 1937. Joining the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ after the War he became a multi-purpose sports broadcaster, but best known for tennis. His rat-a-tat-tat style delivery not only described every shot but a flavour of the occasion. His most famous commentary was Virginia Wade's singles title win in 1977:

"Match point, second serve. Stove serves, it's right, a forehand return by Wade down the line, Stove can't get it. Virginia has won. Virginia Wade has won the centenary title, with the Queen watching her. Virginia will take tea with the Queen."

Watching in the back row of the Royal Box, listening to his Dad’s commentary via a smuggled-in transistor and earpiece, was his 21-year-old son Marcus Robertson. Marcus recalls:

His preparation before each Wimbledon was meticulous. He used to read up and have loads of cuttings to remember. He'd go to a lot of the events when Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ tennis correspondent in the 50's and 60's, even practicing his famous commentary style in front of the TV.

Professionalism - and Colour TV

The advent of professional tennis at Wimbledon was heralded by the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ. In the late-50's and 1960's ITV had tried competing with the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ's coverage using former champion Fred Perry as a commentator. However their coverage was dogged by advertising and a lack of a coherent sport "network", and they never really outperformed the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ.

In 1967 the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ's Head of Sport Brian Cowgill and Wimbledon Chairman Herman David combined to lay the professional foundations. Cowgill recalled in a 2008 interview:

"We can't go on forever claiming the Wimbledon champion is the best player in the world, because Jack Kramer has thirty-odd who could beat him every day of the week! That's why I was a supporter of open sport. Selfishly, because I as a television operator wanted to have the best in front of my cameras."

Kramer organised a "Wimbledon Pro" tournament in August 1967 on Centre Court, televised by the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ, and its success led to the Championships going "open" the following summer.

Dave Gordon edited both radio and TV output in the 1980s and 1990s. He remembers the set-up well:

"When the TV broadcasting "village" was built each year, it was the largest annual outside broadcast in Britain. Our main studio then was a glorified but temporary cabin, which you could only reach by climbing a huge number of stairs. If you wanted a private word with our presenters like Harry Carpenter or Desmond Lynam, you had to be fit!"

The Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ embraced the digital revolution eagerly, recalls Gordon.

"2001 was a landmark year. Red button and sports website streaming meant we could offer more than coverage of just two courts. Up until then I always felt when I chose to change games on TV I could feel the stabs in the back from viewers who disagreed with my decision."

Museum memories

2017 saw the 50th anniversary of colour TV starting in the UK at Wimbledon, which included a mixture of objects from the Club’s collection supplemented by some great loans. Anna Renton:

"We have from the Science + Media Museum an amazing 1936 Emitron Camera, a 1927 Chakophone radio and a 1968 Bush colour TV set. We also have a robotic SMART head camera on loan from Aerial Camera Systems, the type used on the Umpire's chair to record players during the change of ends, which visitors can have a go at controlling."

I wonder what the Museum will be showing in 2067?

Charles Runcie worked in sport for the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ from 1982-2016.

Wimbledon and the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ

-

Oh, I Say! Wimbledon and the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ

Charles Runcie looks back at the enduring relationship between the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ and Wimbledon and some of the events and characters that helped shape it. -

50 Years of Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ TV Colour

Amanda Murphy tells the story of how the ADAPT TV project reunited a pioneering television crew 50 years after the first colour outside broadcast. -

Wimbledon and the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ

Tennis on the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ 1927 to 2017