For an organisation that had spent much of the previous forty-five years trying to avoid the cult of personality associated with celebrity, the appearance of a new species of presenter β the Disc Jockey β at Broadcasting House was a deeply unsettling experience for the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ. How would this new arrival influence the public image of the Corporation and, just as importantly, reflect its public service principles?

Steeped in a long tradition of conservative and deferential presentation styles, the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was not a natural home for jingle-toting, ad-libbing, fast-talking, free-thinking DJ panache, first seen in America and imported to the UK by the pirate stations. But, if Radio 1 and, to a lesser extent, Radio 2 were to be a success, the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ would have to find a way of accommodating these newest of stars in the broadcasting firmament.

The first job, however, was to identify the type of DJ the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ wanted to employ. And with the fall of the pirates imminent, in the spring and summer of 1967 Robin Scott, the new Controller of Radios 1 and 2 knew exactly where to look.

The principal appeal of the disc jockey to the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was their connection to and relationship with audiences β their loyal fan base. Traditionally, ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ radio broadcasters had respectfully presented a selection of programmes to listeners. By way of contrast, DJs, with their individual style, tone and gimmicks, were the programmes, just as much as the records they played. As Tony Blackburn recalled in an interview for the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Connected Histories project, the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was particularly keen to import the pirate style lock, stock and barrel.

The direct link with audiences was recognised as vital to the development of popular music broadcasting at the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ. It was, nevertheless, an inversion of existing practice where the behind-the-scenes art of programme-making had been king. The relative autonomy of disc jockeys was simultaneously their greatest strength and a significant threat to the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔβs editorial control. As Terry Wogan observed at first hand, this raised a critical issue of trust between the broadcaster and its new representatives.

For Wogan, despite the immediate success of Radio 1, something was lost in translation between the pirates and the new station: βRadio 1 never quite captured the spirit of the pirates, the joie de vivre, the madness of it, the carelessness of it. The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was too professional an organisation to really do thatβ.

Perhaps it could never have emulated the romance of the pirates, land-locked and official. But it did propel its DJs, backed by immeasurably greater resources in both radio and television, into the national consciousness. Pete Murray, who presented two separate programmes on launch day, recalled in his interview with the British Entertainment History Project how he and other DJs of the day βhad the world at our feetβ.

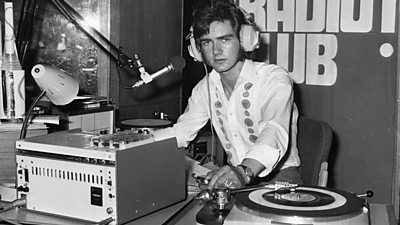

The arrival of disc jockeys not only changed the sound of the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ, but also the techniques of broadcasting itself. On the pirates, DJs had become, by necessity, a one-person production unit: selecting, scheduling, producing and presenting output.

The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ had different staff dedicated to each of these elements. Such professionalism was also an important mechanism for retaining editorial control at the corporate level. However, Robin Scott believed the connection between his disc jockeys and their audiences should be as unfiltered as possible. As such, and to the consternation of many old ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ hands, he insisted on the construction of self-operating studios, which put the DJ more firmly in control.

Disc Jockeyβs have remained at the heart of the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔβs popular music programmes and, since the introduction of commercial stations, have proliferated across the British radio scene. They are loved, parodied and pilloried as fixtures in the cultural life of the nation. Yet, their arrival at the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ in 1967 reflected an uneasy, though mutually beneficial, alliance between insurgents and the establishment they challenged. Nonetheless, the style of broadcasting they pioneered changed the sound of ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ radio forever.

-

ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Oral History Collection

The DJs

-

John Peel

Ken Garner on the Radio 1 broadcaster -

Jimmy Young

The Man from Laramie -

Annie Nightingale

The first female presenter on Radio 1 and its longest-serving presenter