In the autumn of 1967, the executive inside Broadcasting House who was most concerned β and perhaps had most to lose β if the new station didnβt measure up to public expectations, was Robin Scott, the Controller of both Radio 1 and 2. And, as he reveals in this interview, there were difficulties, even before the launch, over defining the status of the new station in the βfamilyβ of ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ services β difficulties that soon centred on the apparently straightforward question of naming each network...

The difficulties in naming that Scott describes are also revealed in this newly-released document in the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ archives - a memo for the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Board of Management written by the Director of ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Radio, Frank Gillard, in February 1967. In it, he notes that the renaming of Radio 4 "appears to downgrade the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Service from its long-established 'flagship' status".

The same memo also argued for the Light Programme, the network with the largest audience, to be given the new title of Radio 1, with the Popular Music Service becoming Radio 2. As we know, these were ultimately reversed, but it gives a sense of the fluidity of thinking in the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ as it grappled with the conceptual, as well as practical, challenges of reshuffling its services

-

Internal ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ memo from Frank Gillard, dated 9 February 1967

The logic of change was clear enough. In the age of television, radio simply had to become more predictable in its output. As the newly-arrived Chief of the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Service and Music Programme, Gerard Mansell put it, the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ needed βto give the networks a greater sense of character and identities, so that the listener would know where to find the kinds of programmes that he or she was looking forβ. The splitting of the Light Programme into two in 1967 allowed the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ to accommodate the political and broadcasting needs for a popular music channel, with a clearer distinction between styles of output β variety and light entertainment, pop music.

Or at least that was the hope.

But as Gillard had noted, re-ordering them in numerical sequence raised the inevitable question of which would be considered as being of principal or least significance. And it wasnβt just the old ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Service that might have felt downgraded. Giving the new pop station the βNumber 1β title also seemed like a demotion for the βleftoverβ elements of the Light Programme, now gathered together in what was called Radio 2.

Matters werenβt helped by more practical issues. Because of a shortage of frequencies and βneedletimeβ restrictions on the amount of recorded music the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ could play on air, the two new stations were forced to share programmes for a large part of the day. Instead of being two networks, it was really βone and a halfβ. People tuning in would hear awkward jumps from T-Rex to Mantovani, from brash youth to gentle maturity.

And as the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔβs own audience research reveals, in the first few weeks after Radio 1βs launch it sometimes looked as if no-one would be happy. In this newly-released document, the Head of the βProgramme Correspondence Sectionβ β a department that monitored letters and phone-calls to the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ β reported that βpop enthusiastsβ were complaining they couldnβt find the programmes they wanted, while βsquarer listenersβ were demanding that βthe whole thingβ be βdone away withβ:

-

Memo from Head of Programme Correspondence Section, 31 October 1967, ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Written Archives Centre.

The Controller, Robin Scott, spotted another, deeper, problem. Reflecting back six months later, he reckoned that Radio 1βs launch had also coincided with a very particular moment in time when musical tastes were fragmenting β and becoming hardened in opposition to each other.

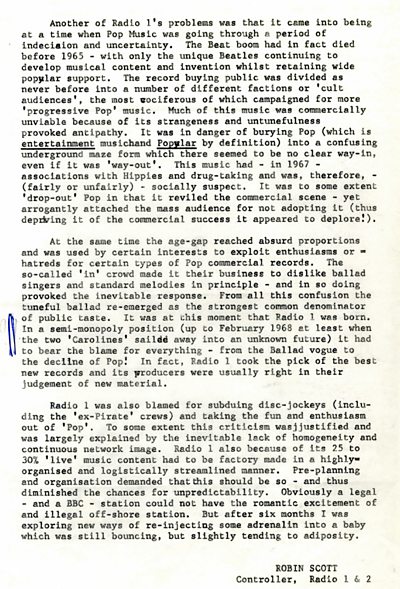

"Another of Radio 1's problems was that it came into being at a time when Pop Music was going through a period of indecision and uncertainty. The Beat boom had in fact died before 1965 - with only the unique Beatles continuing to develop musical content and invention whilst retaining wide popular support. The record buying public was divided as never before into a number of different factions or 'cult audiences', the most vociferous of which campaigned for more 'progressive Pop' music. Much of this music was commercially unviable because of its strangeness and untunefulness provoked antipathy. It was in danger of burying Pop (which is entertainment music and Popular by definition) into a confusing underground maze form which there seemed to be no clear way-in even if it was 'way-out'. This music had - in the 1967 - associations with Hippies and drug-taking and was, therefore - (fairly or unfairly) - socially suspect. It was to some extent 'drop-out' Pop in that it reviled the commercial scene - yet arrogantly attache the mass audience for not adopting it (thus depriving it of the commercial success it appeared to deplore!).

At the same time the age-gap reached absurd proportions and was used by certain interests to exploit enthusiasms or - hatreds - for certain types of Pop commercial records. The so-called 'in' crowd made it their business to dislike ballad singers and standard melodies in principle - and in so doing provoked the inevitable response. From all this confusion the tuneful ballad re-emerged as the strongest common denominator of public taste. It was at this moment that Radio 1 was born. In a semi-monopoly position (up to February 1968 at least when the two 'Carolines' sailed away into an unknown future) it had to bear the blame for everything - from the Ballad vogue to the decline of Pop! In fact, Radio 1 took the pick of the best new records and its producers were usually right in their judgement of new material.

Radio 1 was also blamed for subduing disc-jockets (including the 'ex-Pirate' crews) and taking the fun and enthusiasm out of 'Pop'. To some extent this criticism was justified and was largely explained by the inevitable lack of homogeneity and continuous network image. Radio 1 also because of its 25 to 30% 'live' music content had to be factory made in a highly organised and logistically streamlined manner. Pre-planning and organization demanded that this should be so - and thus diminished the chances for unpredictability. Obviously a legal - and a ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ - station could not have the romantic excitement of an illegal off-shore station. But after six months I was exploring new ways of re-injecting some adrenalin into a baby which was still bouncing, but slightly tending to adiposity."

- Comment by Robin Scott, Controller, Radio 1 & 2, 1968, ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Written Archives Centre.

The ratings, however, were reassuringly huge β with many millions tuning-in to the new service, especially at breakfast time. And the idea of giving networks more individual character β creating clearer differences between them β took hold. Not everyone was happy with this. The disaggregation of programming genres and, by extension, their audiences appeared to some critics to threaten the socially unifying principles of public service radio broadcasting.

Yet, in reality, the changes introduced in September 1967 were not as dramatic as they first appeared. The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔβs family of networks had all already been evolving a greater sense of consistency in output during the three years before Radio 1βs launch.

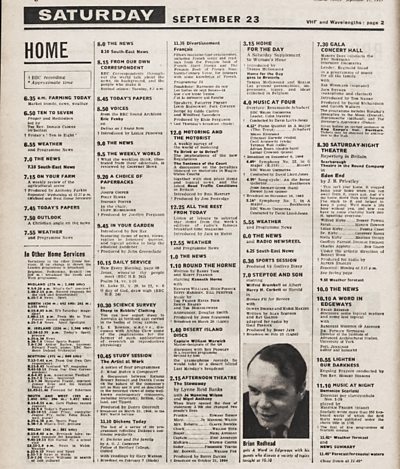

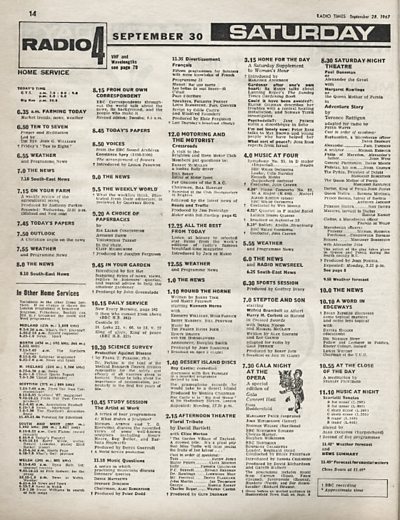

This meant that at the end of September 1967 the schedules of the new Radios 2, 3, and 4 were remarkably similar to those of the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ, Light and Third they had replaced - as can be seen below, when we compare the Radio Times listings for the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Service one week before the launch and then again for Radio 4 on 30 September itself:

The launch of Radios 1, 2, 3 and 4 was hardly revolutionary, then. Rather, it represented a public recognition of the major changes in British broadcasting and the wider cultural climate that had been underway for some time.

In this sense, 30 September 1967 can still be regarded as a significant moment in the evolution of ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ radio more generally. The events that day threw into sharp relief some of the changes already made, and others yet to come - not just in the structures of the networks, but in the Corporationβs whole style of presenting, the place of news and drama on the schedules, even the way we listened to the old box in the corner at home.

Jingles

The identity of a radio station can depend on a number of factors, including: its presenters, the range and diversity of its programmes, formal or colloquial house styles, even the wavelength and technology used to broadcasts on. Over time these combine to leave an imprint that collectively shapes the public profile of a station and individual allegiances to it.

For a new channel, as in the case of Radio 1 in 1967, the need to quickly build positive associations with audiences is acute. One way in which it was thought this could be done, linking Radio 1 to its pirate predecessors and bringing an upbeat dynamic to its programmes, was through the use of βjinglesβ β short musical hooks and motifs that punctuate and brand output.

As with the pirate style itself, this was something the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was keen to import into its popular music station. Interviewed for the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Connected Histories project, Johnny Beerling explains how, with the help of Kenny Everett, the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ went about creating its own line of jingles.

For the Controller of Radio 1, Robin Scott, the jingles needed to emphasis a sense of enjoyment: βa pop network needs to be fun, and jingles are fun β¦β¦ particularly when it helps to make things go with a swingβ.

One potential obstacle, as with the problem of Needle-time and the playing of recorded music on radio, was that the Musicianβs Union would raise significant objections to their use. It transpired, however, that there was no existing arrangement covering the βchoral effort required to record jinglesβ. As Robin Scott recalls, this led to a notorious if rather brief meeting between representatives of the Musicianβs Union and the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ.

Unfettered by external restrictions, jingles quickly abounded across the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔβs popular music services. In doing so, they not only guided listeners through the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔβs new radio soundscape, increasingly familiar as time went by, but also marked out a stylistic lineage that went back to the pirate radio stations and the American broadcasters that had inspired them. And what is more, they still do.

Related links

-

-

-

Creators of the 1967 Radio 1 launch jingles (composer: David Cunningham)