Image: A Â鶹ԼÅÄ camera broadcasts live from the general election count in Exeter, May 1955.

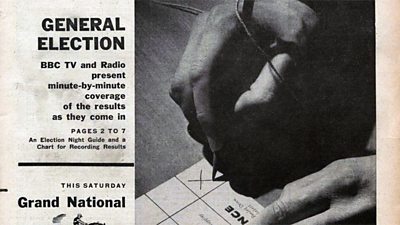

At the beginning of the 1950s the Â鶹ԼÅÄ was still extremely nervous about covering elections in a big way on television. By the 1960s it was happy to boast about it. In the Radio Times there’d be extended features, detailing the extensive facilities and expertise that was now devoted to bringing listeners and viewers all the news and analysis they’d wish for on the night.

But once all the dust had settled and the ballot boxes put back into storage, what did the newspaper critics, the British public – and, indeed, the politicians themselves - make of the programmes the Â鶹ԼÅÄ had broadcast?

The Corporation had been conducting detailed audience research ever since the 1930s. So now, when each election was over, it was possible to get a fairly good idea of how the millions of people watching at home had reacted. In 1955, for instance, Â鶹ԼÅÄ researchers discovered that when TV’s election night programme began, about a fifth of the nation was already tuned in – with numbers rising as soon as the first actual results started to arrive.

By 1959 about 19 million people were watching the results on TV – 13 million of them on the Â鶹ԼÅÄ. Some were even organising ‘newly fashionable television parties’ with friends and neighbours. In 1964, the numbers watching election night programmes – 19 million of them solely to Â鶹ԼÅÄ - even exceeded those tuned-in to the Tokyo Olympics.

Most of these viewers gave high marks to two of the Â鶹ԼÅÄ’s newest stars in the studio - Richard Dimbleby and David Butler. According to the 1955 data Dimbleby was seen as ‘cool, calm, and collected’. Butler impressed people with the speed with which he analysed the data, but also for appearing to be ‘a charming person’.

Other viewers were excited most by the novelty of live cameras being stationed at constituencies across the country. ‘To see votes actually being counted’, the researchers noted, ‘gave a large number a great thrill as this, they felt, was something they would never have seen had it not been for television’.

Professional critics from the newspapers and weeklies were equally struck by the sense of novelty, as each General Election brought a new technological development – whether it was cameras on location, computers in the studio, or increasingly complex graphics on screen. In 1959, the Daily Mail’s TV critic Peter Black described with evident relish a sense of ‘urgency and tumult’ in all the TV coverage.

The Press was quite capable of scepticism, of course. When Harold Macmillan put in a rather sombre performance in a television interview in January 1957 – having been advised privately to avoid cracking jokes – the Economist suggested that because viewers were generally more used to seeing entertainers on screen what they really wanted, even from their politicians, was people who would ‘try to amuse.’

Yet, if anything, Â鶹ԼÅÄ coverage was becoming more serious with each election that passed, not less. By 1964, its producers had a settled style for how to cover grand set-piece events on air. Politicians had also shed any illusions about the importance of TV appearances for creating a good impression among voters, and had brushed-up their act.

The broadcasters and the Westminster parties were now in something of a stand off, each side reluctant to cede too much control to the other. It’s no surprise therefore that some commentators detected a hint of cautiousness creeping into election broadcasting at this time.

In September 1964, the political columnist Anthony Howard wrote in the New Statesman about what he called ‘The Muffling of Television’. There were, he complained, too many stitch-ups between broadcasters and parties over who could appear on air and who should be excluded.

A more serious charge – one that would never really go away - was that election coverage reflected one of the more troubling tendencies of the British media: a narrow fixation on the ups and downs of the Westminster village at the expense of ‘real’ issues affecting ‘ordinary’ voters.

One politician who, ironically, had been among the star performers of TV and radio throughout this period - and who’d actually once worked behind-the-scenes as a producer at the Â鶹ԼÅÄ - was Tony Benn. In this interview recorded for the Â鶹ԼÅÄ Oral History collection in 1998, he recalled his long-standing anxiety about deficiencies in British political reportage:

This charge, though, could perhaps be applied to the regular coverage of politics more easily than to the special category of election results programmes. For, as the Observer put it when describing election night back in 1964, the British public was, at least for one evening every few years, being offered a political ‘orgy’:

Hour after hour of totally compulsive viewability… from midnight on even dumb blackboards, showing the most unexpected no-change results, took on the apocalyptic glamour of stone tablets.

Whatever the style of political reporting to be seen on screen day-in, day-out, there was no denying that by the final three decades of the twentieth century, whenever the polls closed and the counting began, television meant a sense of history was being conjured-up before our very eyes.

-

22.1 MB

Listening to the 1955 General Election on Â鶹ԼÅÄ Radio

In May 1955 the number of British people listening to election results on the radio was roughly the same as the number watching them on TV – the last time radio was to have this equal status in the ratings. The results were carried on both the Â鶹ԼÅÄ Service – the predecessor to Radio 4 – and the Light Programme – the predecessor to Radio 2.

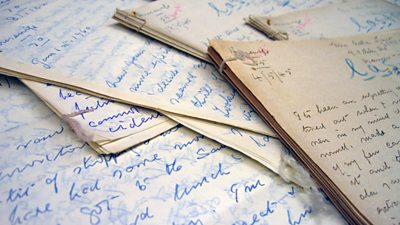

The Â鶹ԼÅÄ’s own Audience Research Department asked several hundred people what they’d liked and disliked. The information they got back is now stored among many thousands of other audience research reports held at the Â鶹ԼÅÄ’s Written Archives Centre in Caversham.

Most listeners were generally satisfied. One is quoting as saying of the election night coverage that, ‘This is the sort of thing the Â鶹ԼÅÄ does supremely well’. But there was notable criticism of an introductory explanation of the evening’s events, which clearly struck several listeners as being horribly patronising in tone. ‘One felt one was a member of a class of half-wits’, said one listener. ‘The announcer’, another recorded, ‘sounded like a senior classics master outraged at having to teach elementary English to ten-year-olds’.

One other finding is worth mentioning. It appears that in 1955, at least, many listeners heartily approved of getting the basic facts, but ‘could rouse no enthusiasm for prophecies and theories which would in any case be proved or disproved on the morrow’.

-

1.85 MB

Watching the 1955 General Election on Â鶹ԼÅÄ television

For the 1955 General Elections results on Â鶹ԼÅÄ TV, the peak viewing time came just as the first actual results started coming into the studio from the constituencies. Most viewers switched off once midnight had come and gone. But not everyone. About one in 20 was still watching between 2.00 and 2.30am.

Most – in fact an impressive 94% of those surveyed – were ‘completely satisfied with the way television handled the general election results’ – and, as the official Audience Report itself reveals, there was even some reference to the programme as the Â鶹ԼÅÄ’s ‘best effort since the Coronation’.

The document shows that, although viewers generally warmed to both Richard Dimbleby and David Butler among the studio presenters, they had a less ‘vivid’ impression of either Robert MacKenzie or E.R. Thompson, the other two personalities on screen. When coverage switched from the studio to outside broadcasts showing various counts across the country, one or two viewers liked this as a welcome break from the routine.

In the words of one respondent, it ‘brought the excitement and atmosphere of the election right into the front room’. The report goes on: ‘To see votes actually being counted gave a large number a great thrill as this, they felt, was something they would never have seen had it not been for television’.

-

3.9 MB

General Elections in Mass Observation

Mass Observation was a large-scale project that began in 1937 and ran through to the 1950s, in the hope of creating what its founders called an ‘anthropology of ourselves’. A panel of volunteer writers and a number of observers were recruited, and aspects of ordinary life were then recorded in diaries or special questionnaires.

The Mass Observation records are now held by the University of Sussex in a specially built archive centre, The Keep, and can be accessed by members of the public by appointment; some are also available online.

General Elections (as well as numerous by-elections) are among the topics about which the panel of diarists was asked to comment. There are, for instance, detailed replies about the 1945, 1950, 1951, and 1955 elections.

Occasionally questionnaires also asked about newspaper reading habits and other factors influencing people’s views of how to vote. More broadly, there are detailed reports on subjects such as ‘How Britain Feels on Â鶹ԼÅÄ Affairs’ (1949) and ‘The MP and His Constituency’ (1949).

For the 1955 General Election, Mass Observation had more than 200 responses to one series of questions such as: Were you interested in the election? Did you ‘listen specially to any radio broadcasts by political leaders’? Did you ‘listen’ specially to any TV programmes by political leaders? And what helped you to decide how to vote?

From the answers it seems as if Mass Observation panellists were more likely than the British population as a whole to have heard politicians on the radio than on TV. A significant portion was claiming not to have heard any politician on either medium.

It’s a reminder that even in 1955 there was still very little political debate on air: election coverage was still concentrated, not on the campaign, but on the reporting of results when the polls closed.