The indifference exhibited by the majority of the political class towards television and political broadcasting in the early 1950s had, a decade later, evaporated. By the time of the 1964 General Election, the coverage of politics had acquired a truly national audience.

Television was recognised as particularly important, with access to the nation's screens seen as a prerequisite of political success. A new 'television generation' of broadcasters and politicians had emerged, making and appearing in programmes directed at an audience increasingly well-versed in the emerging conventions of current affairs and election coverage.

This maturing outlook was reflected in the style and confidence with which these programmes were produced. It was also evident in the competition between politicians and broadcasters to exercise control over this mass media tool. It was in this vein that the Leader of the opposition Labour Party, and one of the most celebrated of the new generation of televisual politicians, Harold Wilson went to see the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ's Director-General Hugh Greene on the eve of the 1964 General Election...

Behind the camera, changes were also in evidence. The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ sought to reconcile the disparate elements of its election coverage β across television, radio, news and current affairs β around a united editorial approach. As Paul Fox explains, the quick-fire elections of 1964 and 1966 provided just such an opportunity...

The broadcast innovations of the previous decade or so had informed the growing political interest in the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ's coverage of politics. But the attention paid to output by the party machines also ushered in a new caution on the part of programme-makers as partisan election strategists increasingly targeted their activities. However, new initiatives with enduring impact were launched β for example, the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Election Call programme, where politicians were questioned and challenged by members of the public.

Radio and television transformed the conduct of elections, not just in terms of the politicians we see and hear, but also how we understand and participate in the political process.

The results programme, as Grace Wyndham Goldie had first noted, has continued to thrive on the βdramaβ of elections. Political and academic commentators vie for attention against ever more elaborate, and increasingly virtual, methods of data visualisation. It is a place where dry analysis and specialist knowledge are met by the smell of grease paint and an eye for entertainment. Audiences and political candidates experience the same mixture of apprehension and excitement as the nation decides.

Anxieties about the distorting nature of election coverage were, to some extent, justified. Broadcasting has re-made electioneering in the United Kingdom, as elsewhere in the world, with an over-emphasis on the presentational qualities of political argument. At the same time, it has fostered and produced public political debate on a scale previously unimaginable, thereby broadening and enhancing the political landscape considerably.

Once the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ had let the genie out of the bottle, there was no going back.

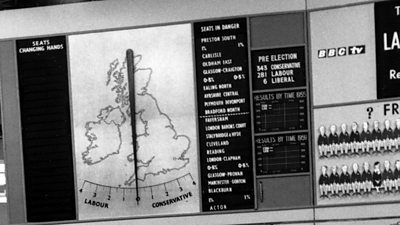

The Swing Indicator

The importance of exploring new visual methods with which to illustrate the story of the night grew with every successive election after the first television coverage in 1950. In the United Kingdomβs first-past-the-post system, where the final result may be many hours away, identifying the electoral βswingβ quickly became a core element of the election narrative.

Amendments and recalculations of the swing allowed for a regular stream of fresh indicators that could be debated at length in the studio β a real advantage in a programme that might last almost 24 hours. It became essential to the drama of the night and from the very beginning took hold of the public imagination.

As Michael Peacock noted after the 1959 election programme, the first to use the device on a national scale, the βSwing Indicatorβ was 'A great if somewhat unexpected success. The idea might be extended to a map showing small swing indicators for the different regions of the country.'

Enhanced by the corresponding development of computers in election coverage the βSwingometerβ, as it became known, has subsequently claimed its place in the hearts and minds of successive generations of broadcasters and audiences.

Smethwick

There is one instance of racially offensive language in this article.

The 1964 election night coverage was slick and exhaustive β probably the most complex programme the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ had done for five years. But one brief moment of television stood out as unusually dramatic: the results coming in from the West Midlands constituency of Smethwick.

Thereβd been a hugely controversial campaign in Smethwick. Early on, the Labour candidate, Patrick Gordon Walker, had been expected to win. But a campaign slogan was then circulated, which used highly derogatory language: βIf you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labourβ.

It was a slogan that his Conservative opponent, Peter Griffiths, had refused to disown. When the polls closed nationwide, there was a swing towards Labour across most of the country, but in Smethwick thereβd been a dramatic swing in the opposite direction, towards the Conservatives. Peter Griffiths took the seat.

When the defeated Walker appeared on screen soon after the results were announced, a sense of shock was written on his face for all to see.

-

Malcolm X in Oxford Hear about the Smethwick election result in this 2014 Radio 4 documentary for Archive Hour about the visit of Malcolm X to Britain in 1965.

-

England in 1966: Racism and ignorance in the Midlands ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ News article by Rebecca Woods, 1 June 2016