Introduction to the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment was a period of discovery and learning in philosophy, science and culture in Europe and North America. It covered a period from around 1680 to 1815.

The Enlightenment, and the years after, brought greater understanding of the human body and how it works. Scientific methods and use of observation, experiments and evidence all led to major improvements in medicine and public health.

Several key people were at the forefront of this age of progress and change.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYPioneers of anatomy and surgery

Up until the 18th and 19th centuries, our understanding of anatomy was very different.

Pioneers such as William and John Hunter changed how we understand human bodies and improved surgical outcomes.

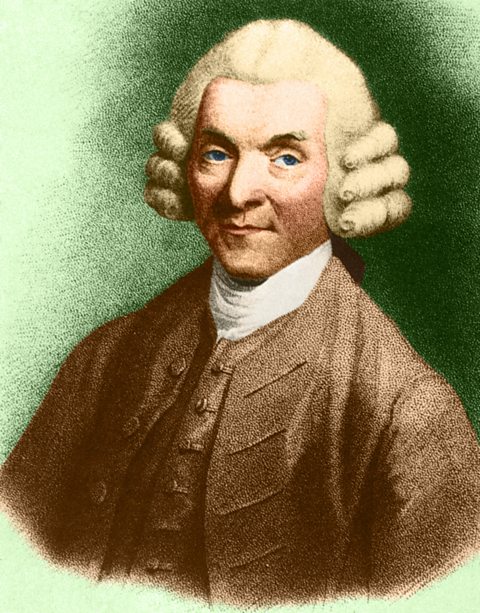

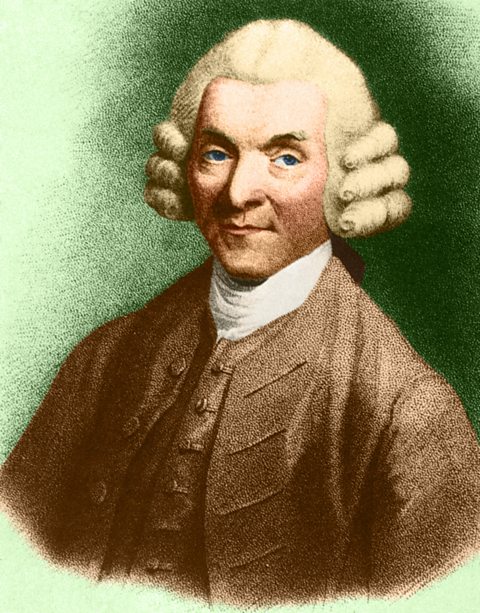

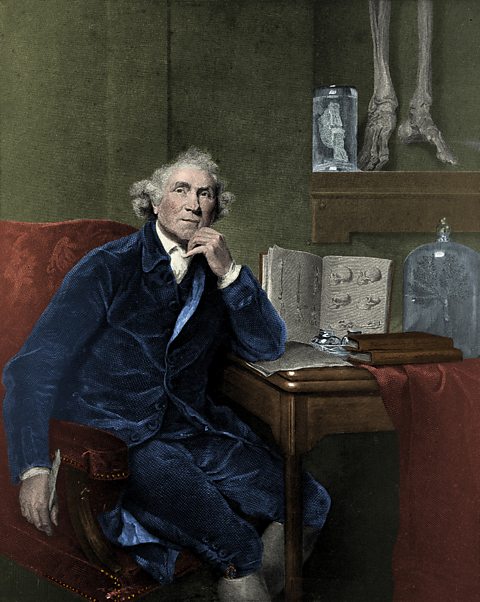

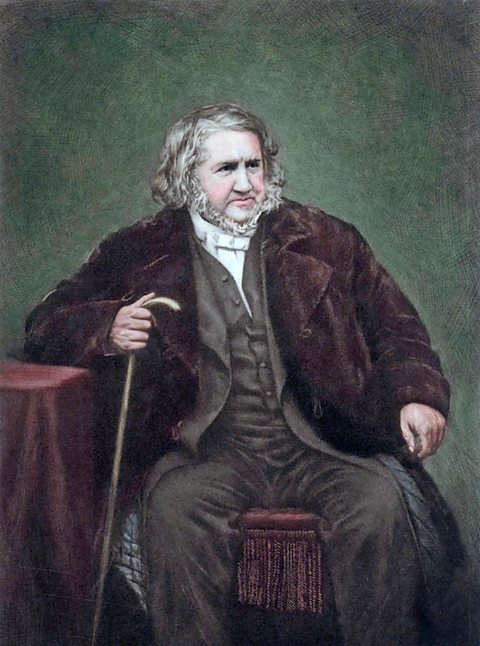

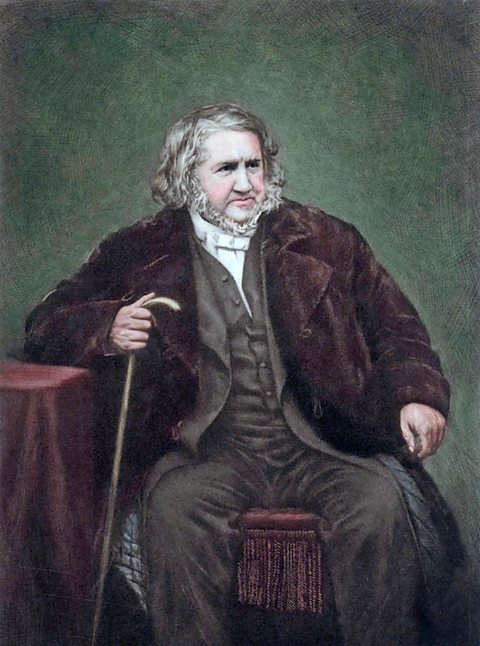

William Hunter, 1718 to 1783

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe work of brothers William and John Hunter led to improvements in our understanding of the human body.

Born in what is now East Kilbride, William Hunter studied medicine at Glasgow University before moving to London.

In London, he studied anatomyThe scientific study of the structures of the human body and how they work and specialised in obstetricsThe branch of medicine that deals with pregnancy and childbirth..

He began to teach anatomy through dissecting human bodies. He eventually set up an anatomy theatre and museum where surgeons would study and learn.

Image source, ALAMY

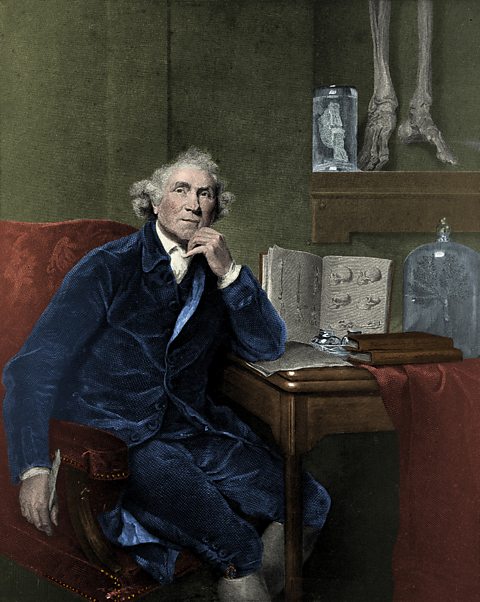

Image source, ALAMYJohn Hunter, 1728 to 1793

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYJohn Hunter had no medical training but joined his brother in London and assisted his work. He became an army surgeon before returning to medical practice in London.

Basing his work on observation and evidence, John Hunter advanced new theories about teeth and bones, digestion, and about the working of the lymphatic system.

Through his work as a surgeon and through experiments, Hunter put forward the theory that inflammation was part of a body's response to disease rather than part of a disease itself.

John Hunter observed that internal injuries did not usually result in inflammation, but external wounds or injuries did.

He believed that surgeons should understand how the human body worked and how it responded to disease and injury.

He taught students such as Edward Jenner to experiment and carry our research and use what they found out to improve treatment of their patients.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYPioneers of microbiology and disease

During the 18th and 19th centuries, pioneers such as Edward Jenner, Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister and Robert Koch changed our relationship with microorganisms and disease through vaccinations and improved hygiene.

Video â Microorganisms and disease

Find out how the study of invisible germs and bacteria led to the eradication of one of the world's deadliest diseases. In this video, learn about Edward Jenner and explore breakthroughs in medicine during the 18th and 19th Centuries.

In Britain in 1757, a sinister enemy lurked: smallpox, a highly contagious and deadly disease that had already killed hundreds of millions of people worldwide. The young were particularly vulnerable to this merciless killer. But a glimmer of hope emerged with a risky method called inoculation.

Thousands of children were deliberately infected with a small amount of smallpox, in the hope that they would develop a mild case and become immune. And it was one of these children, that would go on to revolutionise vaccination against the disease. His name? Edward Jenner.

For over three thousand years, smallpox devasted mankind. In 18th century Europe, this âspeckled monsterâ killed roughly 400,000 people every year, and for centuries there was no cure.

There wasnât much understanding about germs and microbes, or how they actually caused illness. Doctors mainly focused on treating illnesses rather than preventing them. With inoculation came the first attempt at prevention.

Inoculation had been a standard practice in many countries long before it reached Europe. The first attempts recorded were in ancient China, when people would inhale powder made from the crusts of smallpox scabs to gain immunity.

But the risks were immense! People could become contagious and spread it to others, while others developed the full-blown disease and died within days of being inoculated. And this is where Edward Jenner comes in.

Jenner noticed that milkmaids who caught cowpox â a disease related to smallpox but far more mild â didnât catch smallpox. This gave Jenner an idea â could you safely infect someone with cowpox to prevent them from potentially deadly smallpox?

So, he first inoculated a young boy, James Phipps, by scraping the pus from a cowpox sore on a milkmaid â gross! â and pressing it into a cut on his arm. Later, Jenner gave Phipps pus from a smallpox patient, a potentially deadly risk. But the boy didnât get sick! The cowpox inoculations saved him from smallpox.

Jennerâs theory was proved right, although he wasnât exactly sure why. Jennerâs discovery showed that exposing the bodyâs immune system to a safe level of infection could teach it to recognise and fight off future infections. Jenner called this method vaccination, from vacca â the Latin word for cow.

But this ground-breaking discovery as not widely accepted initially. Religious opposition, Jennerâs limited scientific reputation, and even fear that being infected with cowpox could turn people into cows, all stood in the way.

But over time, Jennerâs discovery began to take hold and the approach to medicine shifted to preventing and protecting people from disease through vaccinations. Mass vaccination programmes were introduced in the UK in the mid-1900s to protect the public from diseases such as measles and polio.

And all of this is thanks to Jenner, who became hailed as a â great benefactor of mankindâ.

And smallpox? Completely eliminated in 1980.

Edward Jenner, 1749 to 1823

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe biggest breakthrough in the treatment of disease at this time was the development of the vaccinationVaccinations prevent illness by stimulating the body's immune system. A vaccine - usually a small or weak strain of a disease - is injected into a person. The body's immune system fights the disease. Later, when the body encounters the full disease, it is better able to resist it. for smallpox by Edward Jenner in 1796.

SmallpoxSmallpox is a highly contagious virus that can disfigure and even kill those it infects. Its symptoms include fevers, ulcers, and painful blisters that cover the skin. was a killer disease which was responsible for the deaths of thousands of children and adults.

Before Jennerâs discovery, doctors tried to treat smallpox by inoculations â they would spread the pus of a smallpox pustule into the cut of a healthy personâs skin.

The aim was that the healthy person would develop a mild case of the disease and then never get it again. If the treatment was successful, the person would gain immunity. But there was the risk that someone might contract the full-blown disease when they were being inoculated, or they might not be given enough so they would not develop immunity.

Whilst this worked, very little was known about AntibodiesAntibodies are a protein made by the body's immune system in response to the presence of foreign, harmful substances such as bacteria. and the risks associated with inoculation were great â if the strain of smallpox was stronger, the inoculated individual could die as a result.

Jenner had heard that that milkmaids who caught cowpox never went on to catch smallpox. Jenner thought that the two diseases were very similar and so he conducted a series of trials and experiments to prove the link between them.

In 1796, Jenner took cowpox pus from a milkmaid, Sarah Nelmes, and smeared it into a small cut in the arm of eight-year-old James Phipps. Phipps became mildly ill with cowpox. Next, Jenner gave Phipps pus from a smallpox victim and James did not become ill.

Jenner had shown that infection with cow pox could protect someone from small pox. He called the procedure vaccination â vacca is the Latin for cow â and published a book in 1798 which presented his findings.

Despite the ground-breaking nature of this discovery, vaccinations were not embraced by all immediately. There were several reasons for this.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWhy did people not trust vaccinations?

- There was no real understanding of germs and microbes and how they could cause illness

- Many people did not like the origins of the vaccine. There was even a fear that infecting people with cowpox could cause them to grow horns or turn into cows!

- Jenner was not a famous London doctor, and this prevented some people from taking him and his ideas seriously.

All of these reasons contributed to the governmentâs slow response in making vaccinations mandatory for all young people. It wasn't until 1853 that a law was introduced making it compulsory for all newborn babies to be vaccinated against smallpox.

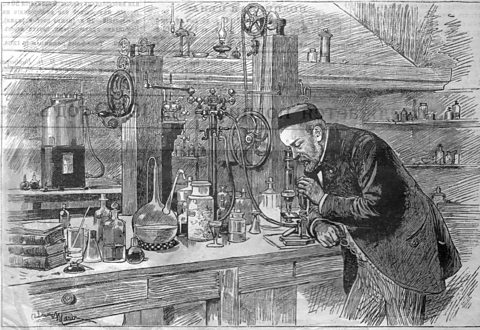

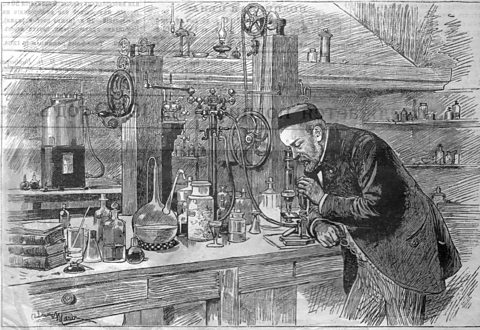

Louis Pasteur, 1822 to 1895

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYTheories surrounding microbes and germs began to evolve due to the work of Louis Pasteur. Pasteur was a French scientist who discovered that bacteria caused diseases â this was known as Germ Theory.

Germ Theory progressed and developed over various stages - initially Pasteur was unable to prove his theoryâs value as he was unable to identify the specific bacteria that caused individual diseases to develop.

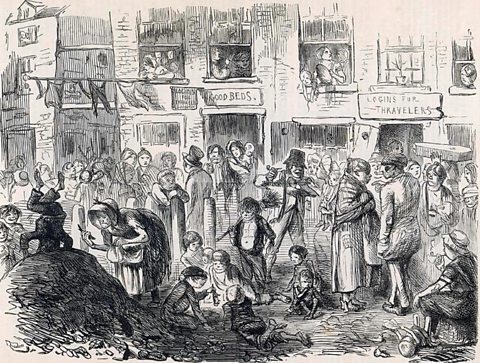

Since bacteria could not be seen by the naked eye, many people still believed that diseases were caused by bad air. This was because they could see rotting food, flesh and the filth in the streets (all caused by bacteria) and assumed that the smells produced as a result caused the spread of disease.

Image source, ALAMY

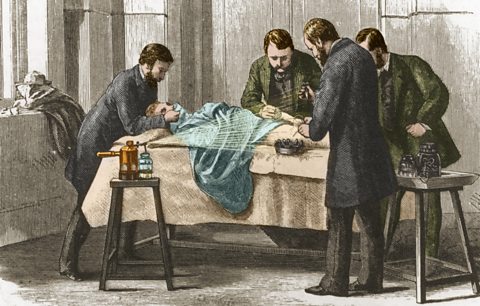

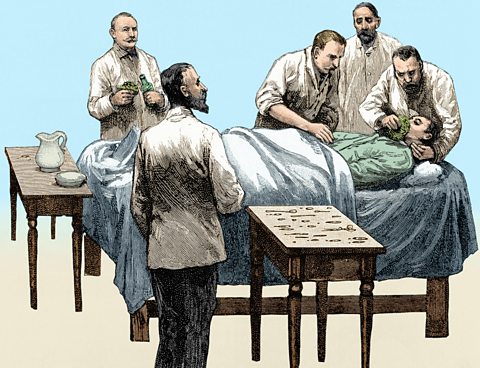

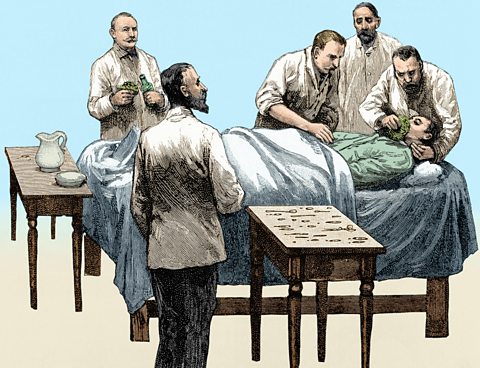

Image source, ALAMYJoseph Lister, 1827 to 1912

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMY Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYJoseph Lister, a surgeon, was aware of Pasteurâs research on Germ Theory and linked bacteria entering open wounds with the development of infection.

He sought a way to prevent this from happening and took inspiration from how the city of Carlisle dealt with their sewage. To prevent the smell of the sewage spreading across the city, carbolic acid was poured over it, neutralising the bacteria.

While a surgeon in Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Lister began to experiment with carbolic acid, applying it to the patientâs wound and to the dressing used to cover it. His findings showed that the wounds healed and did not develop gangrene, preventing many unnecessary deaths.

Lister findings also led to several other reforms in medicine. Doctors and nurses were now expected to wash their hands in carbolic acid before an operation to prevent infections developing and they were to use a carbolic spray to kill germs in the air around the operating table.

Lister also built on the discoveries of the influential 16th century French surgeon, Ambroise Paré, by developing antiseptic ligatures to tie up blood vessels to prevent blood loss after an amputation. Paré had attempted to use catgutA strong cord that was made from the dried intestines of sheep, goats or cows. It was used by surgeons to tie the severed ends of arteries and veins to stop bleeding. but many died as a result of infections.

Although study of anatomy had improved surgery, deaths after operations such as amputations were still high because of infections. Between 1864-67, the death rate from amputations sat at 46%!

Surgical tools were not cleaned before operations, doctors wore filthy clothes and did not even wash their hands before carrying out procedures.

By the late 1890âs operating theatres were rigorously cleaned and sterilised, all medical instruments were steam-sterilised and surgeons began to wear surgical gowns, with face masks and rubber gloves.

Image source, ALAMY

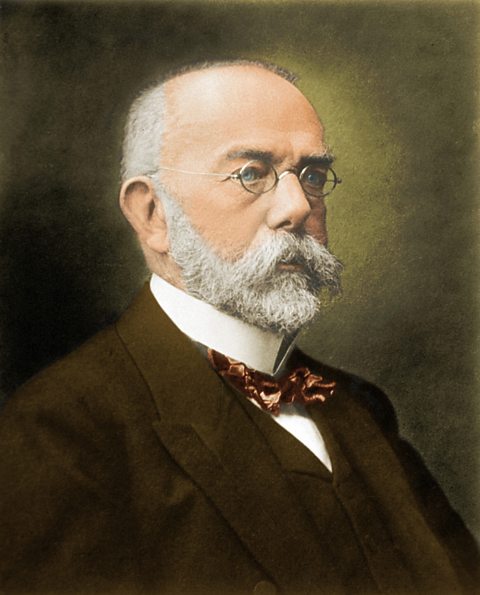

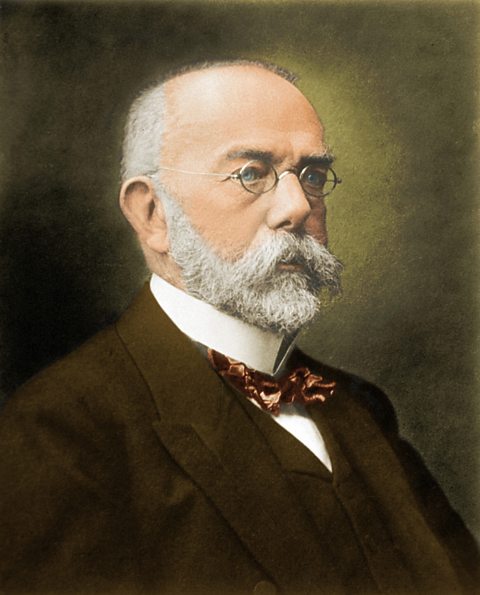

Image source, ALAMYRobert Koch, 1843 to 1910

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYGerm Theory had increased understanding of microorganisms causing infection and disease. But the link had not yet been made between specific bacteria and specific diseases.

All this changed in 1876 when a German doctor called Robert Koch discovered the bacteria responsible for causing AnthraxAnthrax is a deadly infection caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis. It commonly infects animals and livestock but can also be spread to humans., by building on Pasteurâs theories.

Over the next 20 years Koch and his team were able to identify further individual bacteria that could cause disease, including those that led to septicaemia, tuberculosis and cholera.

With this new research and knowledge, Pasteur went on develop vaccines for anthrax and the RabiesRabies is a disease that causes inflammation of the brain and nerves. It can affect all mammals including humans and, untreated, can be deadly. Rabies is typically contracted after being bitten by an infected animal. virus.

Importantly, as a result of these findings, people were persuaded that bad air was not the cause of disease.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYPioneers of anaesthetics

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYOperations in the early 19th Century were a thing of horror â surgeons believed that the only way to reduce the pain felt by the patient was to operate as fast as possible!

One Scottish surgeon, Robert Liston, was proud of the fact that he was able to amputate a leg in two and a half minutes!

The scientist Humphrey Davy, in 1800, discovered that laughing gas (nitrous oxide) could be used as an anaesthetic however, whilst this reduced the amount of pain the patient felt, it did not completely remove it.

Davy promoted his discovery with public demonstrations however these demonstrations did not always have the impact he intended â despite the danger of inhaling too much nitrous oxide causing unconsciousness or even death, laughing gas parties became a popular event as a result of the effect of the gas on individuals.

Image source, ALAMY

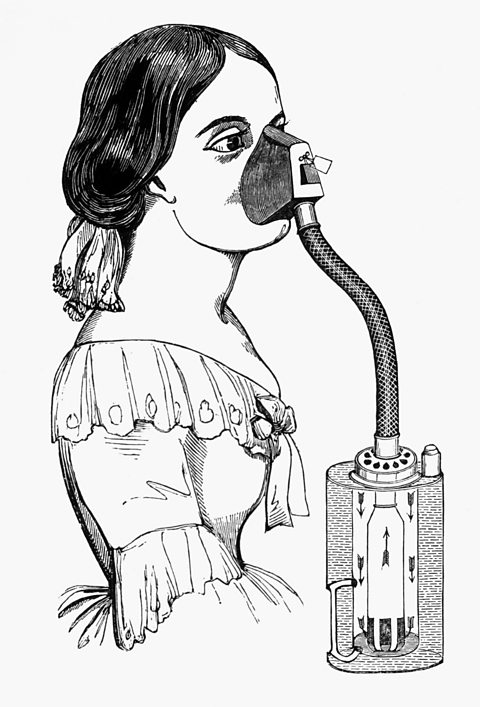

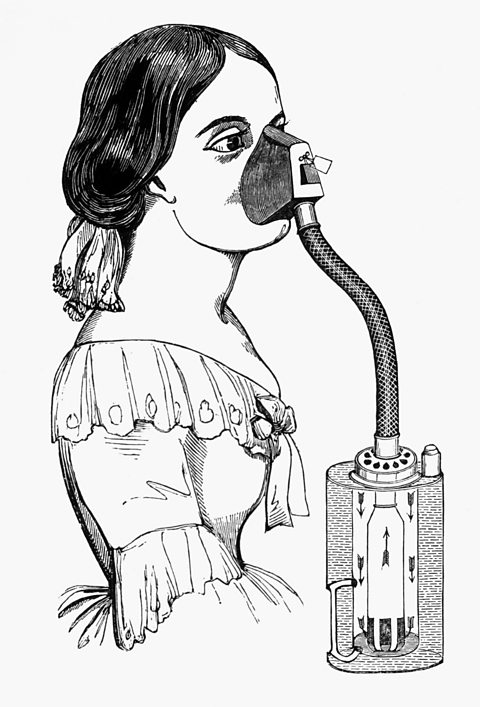

Image source, ALAMYJames Simpson, 1811 to 1870

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe search for a more effective anaesthetic continued until 1847, when James Simpson, a Professor of Midwifery at the University of Edinburgh, discovered the anaesthetic properties of chloroform whilst conducting an experiment with his dinner guests.

Before the dinner, Simpson gave each guest a tumbler containing chloroform and, after each of them had inhaled the fluid, promptly collapsed at the table â much to the horror of his wife!

Within days, Simpson was using chloroform to help women in childbirth and other operations. When the results of his findings were published, other surgeons began to use it in their own operations.

Chloroform could knock people out for longer operations and so gave surgeons more time when operating. Surprisingly, there were objections to the use of chloroform:

- Some surgeons preferred their patients awake so that they could fight for their lives.

- Some religious people felt that pain (particularly in childbirth) had been sent by God and should therefore not be tampered with.

- It was difficult to get the dose right. A 15-year-old called Hannah Greener died while having her toenail removed.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYJohn Snow, 1813 to 1858

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe method of delivery of chloroform to the patient before a procedure was refined in 1848 by Dr John Snow. Snow created an inhaler to regulate the dose administered, reducing the danger of killing the patient by using too much.

The use of chloroform, whilst reducing the pain felt by the patient and allowing the surgeon to take their time, did not make surgery any safer as infections from dirty equipment still occurred.

Chloroform gained a wider acceptance amongst the medical profession after Queen Victoria used it in the delivery of her son, Prince Leopold, in 1853.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYPioneers of blood transfusion

Blood transfusions had been carried out since William Harvey discovered how blood circulated in 1628:

- 1665 â Richard Lower successfully kept a dog alive by transfusing blood from other dogs.

- 1667 â both Lower and Jean-Baptiste Denis successfully transfused sheep blood into human patients.

- 1668 â blood transfusions from animals to humans were banned in Britain and France. One reason for this was the high death rate.

Before abandoning his research, Lower designed equipment to control the flow of blood. These had many similarities to modern syringes and catheters.

James Blundell, 1790 - 1878

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYIn 1818, the British obstetrician James Blundell performed the first successful human to human blood transfusion.

The recipient was a woman who had suffered blood loss after giving birth. Blundell took blood from the patient's husband and used a syringe to transfuse it into the patient's arm.

Through the 1820s, Blundell performed ten transfusions, five of which were shown to help the patients.

In the mid-1800s, Edinburgh became a centre for blood transfusions. James Simpson successfully used transfusions to treat his obstetric patients.

However, transfusion remained a risky procedure and many patients died. At the time there was no understanding of blood groups. No-one knew that if the donor and patient had different blood groups, the patient's immune system responding causing the blood to clot, which could be fatal.

It wasn't until 1901 that an Austrian physician, Karl Landsteiner, discovered the first three blood groups. This led to the matching of blood types which ensures that blood transfusions are safe today.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYImprovement in patient care

Alongside the development of medical treatments and expansion of medical knowledge, the 18th and 19th centuries bore witness to improvements in patient care.

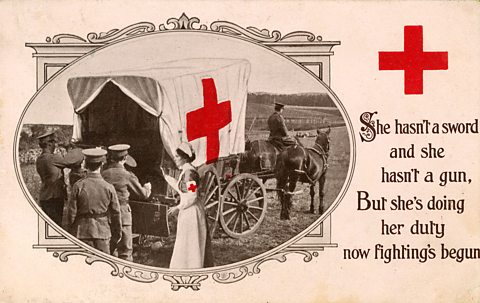

Two women who played a role in this were Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole â both of whom were involved in treating injured men during the Crimean War, 1853 - 1856.

Both Nightingale and Seacole recognised the importance of housing sick men in a clean environment whilst they were recovering from their injuries.

Florence Nightingale, 1820 to 1910

Image source, ALAMY

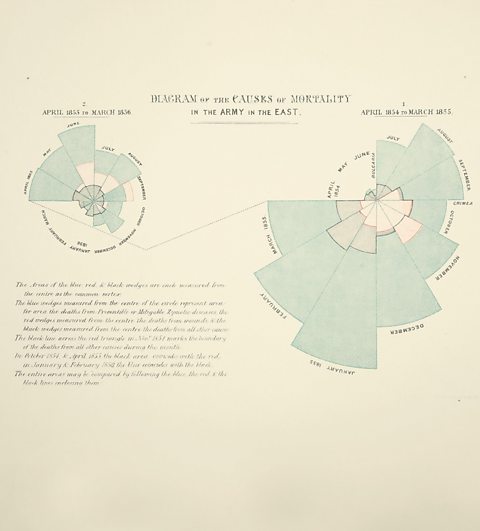

Image source, ALAMYFlorence Nightingale introduced the use of statistics into medicine.

She collected data on illness and death and discovered that more soldiers were dying as a result of unclean conditions in the hospitals than as a direct result of battlefield injuries.

She presented her findings in a diagram which gave a clear visual representation of causes of death. Nightingale proposed simple measures to improve conditions:

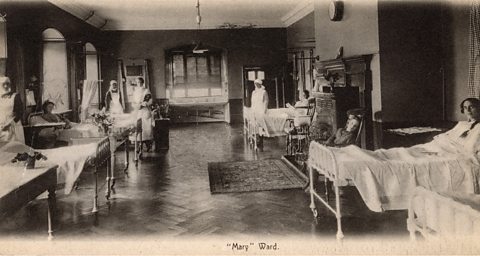

- Patients were separated according to their illness.

- Beds were spaced apart and clean air was allowed to circulate.

- Strict hygiene rules were enforced, eg patients were washed and bedding was changed regularly.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMY Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYUpon her return to Britain after the war, Nightingale established the Nightingale Training School at St Thomasâ Hospital. She aided the transformation of cleanliness in hospitals using the knowledge that she had acquired during her time abroad.

Mary Seacole, 1805 to 1881

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYBorn and raised in Jamaica, Mary Seacole was the daughter of a Scottish soldier and a free black Jamaican.

Her mother was a 'doctress' who cared for sick people using traditional African and Caribbean herbal remedies.

Mary learned how to diagnose disease and care for the sick from her mother. She put this into practise during a cholera epidemic in Panama and an outbreak of yellow fever in Jamaica.

At the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1853, Seacole volunteered as a nurse but was refused. In her autobiography she questioned whether this was a result of racism. Instead, she raised her own funds and travelled to Crimea, setting up her own 'British Hotel' where she tended to sick and injured soldiers.

Like Nightingale, Seacole understood the importance of the conditions in which patients were kept. She practised good hygiene, her rooms were warm and well ventilated, and she ensured patients were well fed and hydrated.

Seacole is rightly remembered for treating her patients as people rather than just bodies to be healed. William Russell, War Correspondent for The Times said this of her:

A more tender or skilful hand about a wound or a broken limb could not be found among our best surgeons.

After the war ended, she spent her time between Britain and her homeland of Jamaica before her death in 1881.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYTest your knowledge

More on Medicine through time

Find out more by working through a topic

- count5 of 8

- count6 of 8

- count7 of 8

- count8 of 8