Key points

- After World War Two, Britain needed to be rebuilt, but faced a severe labour shortage. The government decided to invite people from the Commonwealth to come and work in Britain.

- The 1948 British Nationality Act said that all Commonwealth citizens could have British passports and work in the UK.

- ​​Conflict in India and Pakistan in the years following Partition, the expulsion of Ugandan Asians and unrest elsewhere in Africa all contributed to an increasing number of migrants to Britain after World War Two.

Video about post-war migration to the UK

Narrator: People from all over the world have migrated to and from the UK for centuries. After World War Two, people had more opportunities to travel to the UK from the Caribbean, Asia and Africa. Everyone has their own story about why they moved and the challenges they faced.

Jamaican woman: I worked in a hospital in Kingston, Jamaica. The Jamaican economy was not doing well and jobs were scarce for my husband. I’d heard that the new National Health Service was looking for nurses. The British Nationality Act of 1948 offered British citizenship to everyone in the British Empire. So we bought our tickets and sailed to the UK. I was offered a job in an NHS hospital.

My husband eventually found work on the railways and our children started at a local school. We suffered much discrimination, but we’re proud of the life we built in Britain.

Indian man: The partition of India and the creation of Pakistan led to great unrest and we didn’t feel safe at home. We wanted a better life for our children in the UK. I arrived in Nottingham in 1957 with three pounds in my pocket. That was the amount the Indian government said we could leave with. I imagined England was full of palaces, the streets paved with gold, but it wasn’t like that.

A year after I arrived, there were racially motivated riots in the city. I found work in a nearby textile factory, thanks to my experience doing the same at home. I saved enough to bring my family over in 1960.

Kenyan man: I fought with the British in the Burma Campaign in the Second World War. When I returned home to Kenya, the British had promised education and employment opportunities. They never came. So I used my life savings and travelled to the motherland. I imagined being welcomed as a hero, but people didn’t want to live side by side with me. When I arrived my life was extremely hard, because of the colour of my skin, people wouldn’t rent me a room.

I was refused entry into the local church and couldn’t even find anywhere to get my hair cut. Eventually, I did find somewhere to live when I rented a room from a Jamaican family.

Narrator: The UK today is home to people from all over the world with many diverse stories and experiences.

The empire after World War Two

After World War Two, Britain was left in ruins. There were thousands of jobs that needed to be filled, as well as homes and companies that needed rebuilding.

The British government offered work to people who were living in the CommonwealthThe Commonwealth was set up in 1926 between Britain and all partly independent countries in the empire, which were also known as dominion states. Eventually other territories within the empire became part of the Commonwealth.. Under the British Nationality Act 1948, all Commonwealth citizens had the same rights to live and work in the UK as British citizens.

Why did people migrate to Britain?

World War Two ended in 1945. In the decades that followed, hundreds of thousands of people migrateWhen a person moves from living in one country or area to living in another country or area. to Britain for different reasons and from several newly independent nations.

- From 1948 to 1971, around 500,000 people migrated from the Caribbean as part of the Windrush generation.

- After the Partition of India in 1947, millions of people were displaced and many migrated to escape the violence. By 1951, it is estimated that there were 43,000 South AsiansPeople from countries in South Asia, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. living in Britain.

- When Ugandan President Idi Amin ordered all 80,000 Ugandan AsiansThe descendants of Asian migrants who arrived in Uganda from the 1890s onwards as indentured servants, and those who migrated after the 1890s. Ugandan Asians were born and raised in Uganda, and many had Ugandan citizenship. to leave the country within 90 days, Britain eventually agreed to resettlementThe process of helping someone, or a group of people, to move to live in a new place. 27,000 of the refugees permanently.

- There had been steady numbers of migrants from West and South Africa to Britain in the 1900s, which increased from the 1980s onwards.

The impact of the Partition of India

Following Indian independence in 1947, many jobs in India also disappeared. People who worked for British companies or in port townA town where ships load and unload goods. Historically there have often been many jobs available in port towns. with British traders were now left without a job. This meant the opportunity to work in Britain was very appealing to many Indians.

Following the Partition of India, Pakistan had a Muslim-majority population, while India had a Hindu-majority population. The Partition of India resulted in the death of 1 million people as Hindu minorities in Pakistan tried to migrate to the new state of India, and Muslim minorities in India tried to migrate to the new state of Pakistan.

Hundreds of thousands more migrated from India and Pakistan to other countries to escape the violence and find a place to rebuild their lives. Some of these people migrated to Britain.

Migration from Kenya and Uganda

32,000 Indians had migrated to Kenya and Uganda in the 1890s to help build the railway between the two British colonies. Many of them were indentured labourerA person who is required to work for a specific period of time, generally for no or very little money. Following the abolition of slavery, the British Empire used indentured labour to send people to work across many colonised countries.. Once the railway was complete, most returned to India. However, several thousand stayed in Uganda to build a new life.

Why was there resentment towards Ugandan Asians?

By the 1970s, the Ugandan Asian population numbered 80,000. The British government invested money into improving job opportunities, housing, and education for Ugandan Asians who chose to stay in Uganda. This meant that although they only made up 1 per cent of the population, they earned 20 per cent of the income in the country. However, many more British settlers owned most of the wealth in the country, with indigenous Ugandans often living in poorer conditions and working lower-paid jobs.

When Uganda became independent in 1962 and Kenya became independent in 1963, most British settlers returned to Britain or migrated to Australia, New Zealand or Canada. After this, there was growing resentment towards the Asian community in Uganda because British policies had benefitted them economically over the indigenous Ugandans.

Expulsion of Ugandan Asians

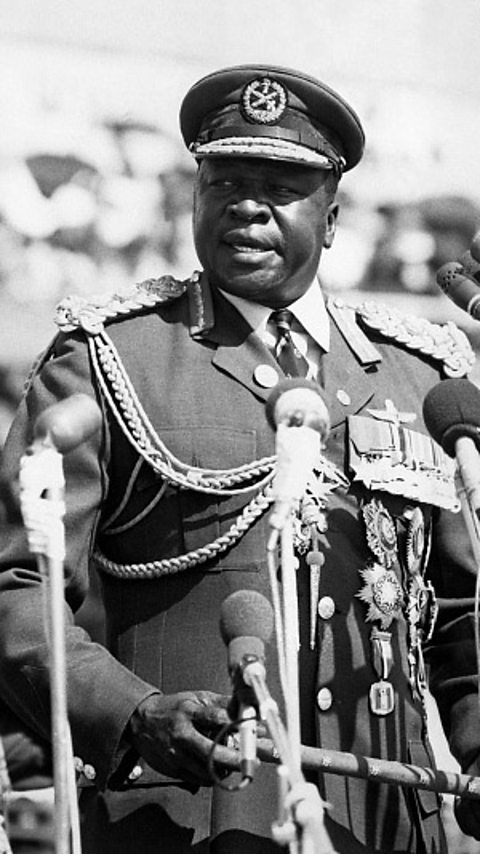

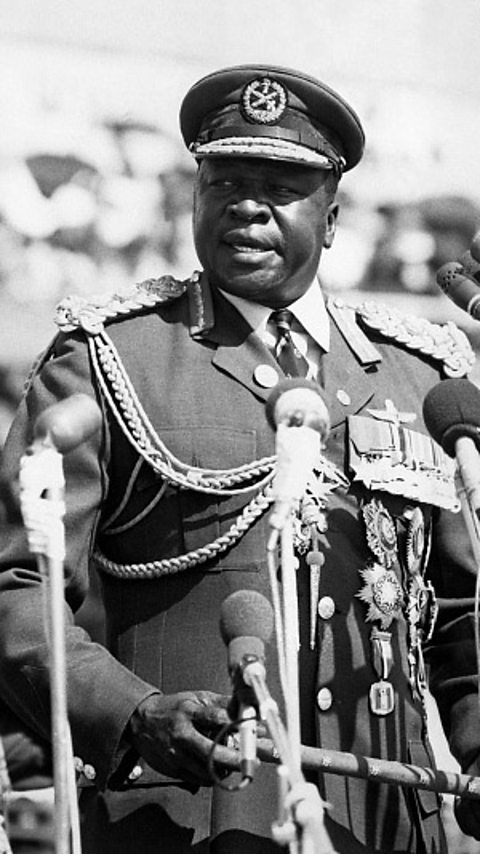

In 1969, the government introduced work permits that would limit the work of Ugandan Asians who were not Ugandan citizens. When Idi Amin became the president of Uganda in 1971, he went much further and declared that Ugandan Asians may lose their citizenship.

In August 1972, President Idi Amin ordered all 80,000 Ugandan Asians to be expelTo force a person or group of people to leave a country or organisation. within 90 days. Amin said that Britain should take responsibility for Ugandan Asians as many of them were Commonwealth citizens. He declared that any remaining in Uganda after 8 November 1972 would be imprisoned in a military camp.

23,000 Ugandan Asians had Ugandan citizenship and were later allowed to stay. However, many chose to leave after Ugandan soldiers carried out acts of violence against the remaining Asian communities. Those in the process of applying for citizenship had their application cancelled and were forced to leave.

How did Britain try to stop the expulsion of Ugandan Asians?

The British government first tried to stop the expulsion by holding back a loan of around ÂŁ10 million that had been arranged for Uganda in 1970. When Idi Amin ignored this, the British government tried to relocate the Ugandan Asian refugees in the remaining British territories, although only the Falkland Islands responded positively.

After much debate, the Uganda Resettlement Board eventually approved the permanent resettlement of 27,000 refugees in Britain.

Migration from West Africa

Early migration from West Africa

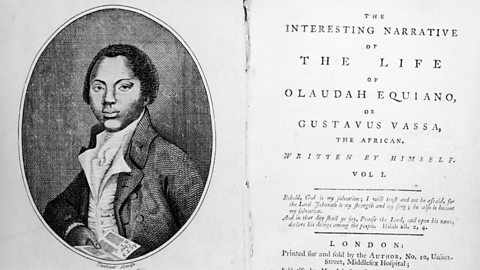

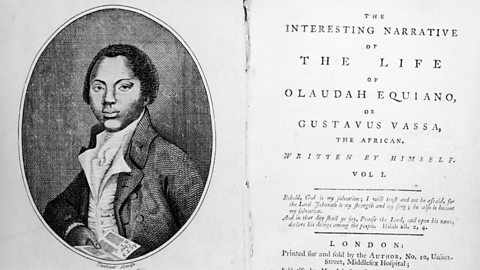

There has been a Nigerian presence in Britain for over 200 years. Olaudah Equiano lived in London in the 1700s. He wrote in his autobiography that he came from the Kingdom of Benin, in what is now modern-day Nigeria. In the early 1900s, it was common for Nigerians to migrate temporarily to study in Britain before returning to Nigeria.

There is evidence that there was a Ghanaian presence in early-modern England. In 1555, John Lok brought five enslaved Africans from a village called Shama, in what is now modern-day Ghana, to England. There is evidence of small groups migrating to England from this part of West Africa from this period onwards, as trade between the two regions continued. Britain eventually colonised this part of West Africa in the 1800s.

Migration since the 1960s

Following Nigerian independence in 1960, migration to Britain steadily increased as political unrest and the Nigerian Civil War, which began in 1967 and ended in 1970, led many people to leave Nigeria. The number of people migrating to Britain from Nigeria steadily increased throughout the 1900s. As of 2019 there are an estimated 215,000 Nigerian-born residents in the UK.

People began to migrate from Ghana to Britain in much larger numbers from the 1960s onwards as the economic conditions in Ghana did not improve as much as expected following independence in 1957. In 1961 a census of the United Kingdom recorded 10,000 residents born in Ghana, which had increased to over 95,000 by 2011.

Changes to immigration and refugee laws

The British Nationality Act 1948 meant that anyone who had a Commonwealth passport had the right to live and work in Britain. Between 1962 and 1971 the British government had put several laws in place to limit immigrationComing to live permanently in a foreign country. from Commonwealth countries, which included Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria and Ghana.

| British Nationality Act 1948 | Anyone with a Commonwealth passport had the same legal right to live and work in Britain as anyone with a British passport. |

| Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 | People with a Commonwealth passport no longer had the automatic right to live and work in Britain, people instead had to apply for work permits. These work permits were mostly given to white citizens in dominion states. |

| Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968 | Commonwealth citizens were only allowed to migrate to Britain if they had a parent or grandparent born in Britain. |

| Immigration Act 1971 | Work permits were replaced with employment vouchers that were only given for a set period of time. This meant that most migration that was allowed would be temporary. |

By 1971, Commonwealth citizens could only be granted entry to Britain with a temporary work voucher. However, after Idi Amin’s announcement that all Ugandan Asians were to be expelled, the British government had to decide how they would respond to the refugee crisis. They decided to allow 27,000 Ugandan Asians to migrate to Britain.

While these 27,000 refugees were able to escape persecutionTreating people poorly based on their political beliefs, race, religion or sexuality. in Uganda, they faced a lot of hostility when they arrived in Britain. Following the mass arrival of Ugandan Asians there were anti-immigration protests by the National FrontA far-right political group formed in the 1960s that believed all non-white immigration should be stopped, and that only white Britons should have British citizenship. They were often involved in violent clashes., a far-right group that wanted to ban all non-white immigration to Britain.

In 2001, a UK census said that 55,000 people in Britain had been born in Uganda. There is still a small Ugandan Asian population in Britain today, although many felt able to return after Yoweri Museveni became President of Uganda in 1986.

Apart from Britain, where else did Ugandan Asians migrate to?

Canada allowed entry to 6,000 Ugandan Asian refugees. 4,500 migrated to India and 2,500 were able to migrate to Kenya. In addition to this, Pakistan, Malawi, West Germany and the USA all agreed to admit 1,000 refugees each following the crisis.

However, there are nearly 20,000 people who are unaccounted for. Many of these would have died in the violence that followed Idi Amin’s announcement, as only a few hundred remained in Uganda.

The Race Relations Act

By 1965, there were almost 1 million immigrants living in Britain. At this time, it was not against the law to treat people differently depending on the colour of their skin.

In December 1965, the Government introduced the Race Relations Act. This new law aimed to prevent discriminationTreating people differently on the basis of a particular characteristic, such as race, religion or sex. on the basis of race. It made it illegal to discriminate against someone because of the colour of their skin or their ethnic or national background in public places, such as cinemas and restaurants.

The government introduced this law because Black and Asian people, who had migrated to Britain after World War Two, had been suffering a lot of anger and discrimination in Britain. The new law was an attempt to prevent this discrimination, but many people of colour continued to face racism. The act did not include public places like shops, and many people suffered discrimination when they applied for jobs.

The Government introduced a new Race Relations Act in 1968, which aimed to address some of the problems that migrants continued to face. It made it illegal for someone to be refused housing, a job or services - such as taking out a loan at a bank - on the basis of their ethnic background.

In 1976, the Government introduced a third Race Relations Act, which specifically defined different types of discrimination.

What happened in Smethwick during the 1964 general election?

In 1964, there was a general election. Peter Griffiths, the Conservative candidate for Smethwick, a town just outside Birmingham, used an extremely offensive racist slogan when he was campaigning against the Labour candidate, Patrick Gordon Walker.

Black and Asian families had suffered racism when they arrived in Smethwick to set up their new homes. Many people who were already living in the area were strongly opposed to immigration.

Griffiths won the election in Smethwick, defeating Walker. Many people across Britain were shocked by the racism of Griffiths’ campaign.

In 1965, the American civil rights activist Malcolm X visited Smethwick. He encouraged Black people living in the town to stand up for their rights.

Test your knowledge

Play the History Detectives game! gamePlay the History Detectives game!

Analyse and evaluate evidence to uncover some of history’s burning questions in this game.

More on Post-war migration from Africa, the Caribbean and Asia

Find out more by working through a topic

- count1 of 2