More guides on this topic

- Classification and biodiversity вҖ“ WJEC

- Cell division and stem cells вҖ“ WJEC

- DNA and inheritance вҖ“ WJEC

- Variation вҖ“ WJEC

- Mutation вҖ“ WJEC

- Evolution вҖ“ WJEC

- The nervous system вҖ“ WJEC

- В鶹ԼЕДostasis вҖ“ WJEC

- The role of the kidneys in homeostasis вҖ“ WJEC

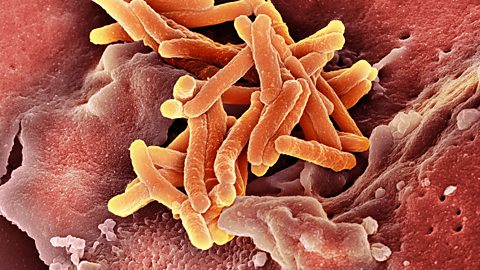

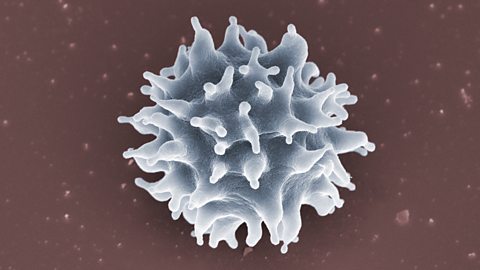

- Micro-organisms and their applications вҖ“ WJEC

- Video playlist