Introduction: social and political reforms

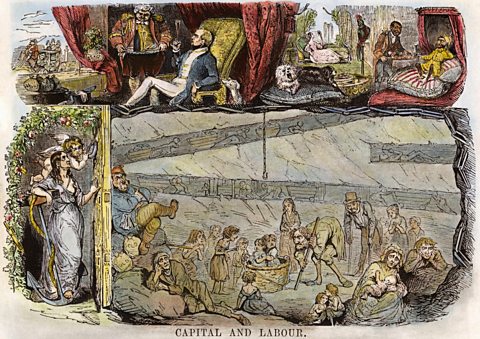

During the Industrial Revolution more and more people moved from rural areas to towns and cities in order to work in factories.

These changes to living and working led to demands for social and political reform.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWorking conditions during the Industrial Revolution

How did industrial disasters lead to important reforms during the Industrial Revolution?

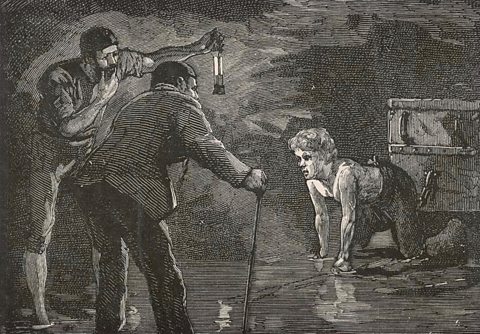

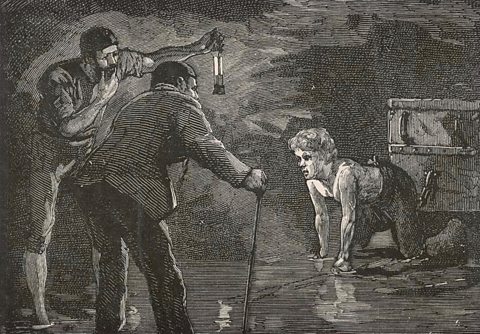

Itâs the 4th of July 1838, and a boy, Uriah Jubb, is working in the depths of the Huskar Pit coal mine in South Yorkshire. Entering his ninth hour underground, he crawls through the narrow, dark and dusty tunnels. Suddenly, a call comes from above. Violent rainfall has flooded the lift engine; thereâs no way out. But the message is unclear.

Panic sweeps through the mine. After hours of waiting, some try to find an exit, but a torrent of water suddenly floods through from above and sweeps them off their feet.

Uriah found refuge higher in the mine, and, hours later, was rescued. But others werenât so lucky â twenty-six children, aged eight to seventeen, were drowned when the Huskar Pit flooded with water.

The tragedy shocked the public and led to calls for reform from all corners of British society. For many people working in mines, factories and mills, life was hard. Think long hours, poor pay, and dangerous working conditions.

Disasters like the one at Huskar Pit were common. Women and children were particularly cheap to employ, and children as young as five worked in coal mines as trappers and putters. Collapsing roofs, floods and explosions were regular dangers, and between 1830 and 1838, 48 fatal accidents occurred in Scotland alone. Something had to change, and disasters eventually led to big reforms.

Upper and middle class social reformers were appalled by the loss of young lives and the frankly inhumane working conditions. Some were getting worried about social unrest.

After the Huskar Pit disaster, a Royal Commission of Enquiry was established, whose report in 1842 dramatically revealed the terrible reality of the conditions that children were being made to work under.

That same year, a law was swiftly passed prohibiting any girls, or women, or boys under ten from working underground, to be enforced by factory inspectors.

Mine, factory, and mill disasters spurred solidarity among workers, who banded together to organise labour movements â they demanded safer conditions, fair pay. Trade unions were established to protect workerâs rights. And public demonstrations and strikes were organised to demand reforms and create pressure for change.

But the reforms that followed had limitations. Predictably, many opposed these reforms. In the words of the Earl of Rosslyn, governments âought to be slow to interfere with free labour.â And so conditions in remained dangerous for years to come.

Nevertheless, these reforms were a welcome step in the right direction.

As the Industrial Revolution progressed, factories and coal mines became major employers.

Conditions in these industrialised places could be poor. Employees were forced to work long hours in environments that often could be dangerous.

Over time, campaigners pushed Parliament to bring in laws to improve the working conditions in some of these key industries.

The Factory Acts

Image source, ALAMY

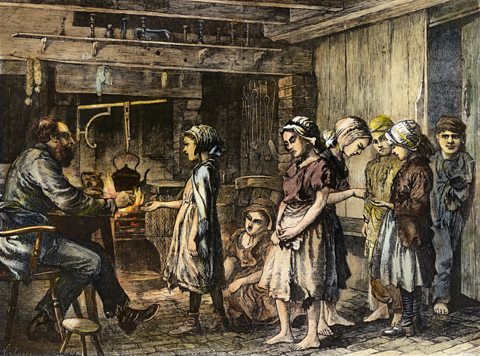

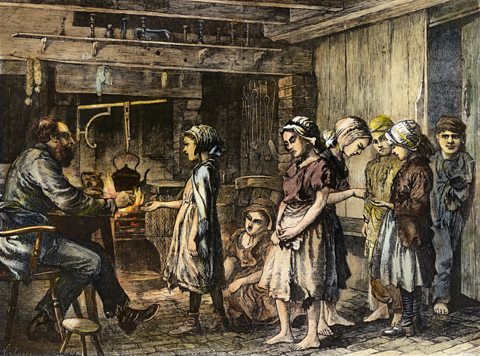

Image source, ALAMYTo improve the lives of factory workers, the UK parliament passed the Factory Act 1833 which forbid children under the age of nine from working in factories.

Children between the ages of nine and thirteen had their working time limited to just nine hours a day!

Inspectors were employed to ensure the factory owners obeyed these laws.

The Factory Act (1844) brought improvements to factory safety. Dangerous machinery had to be made fenced off, with safety guards and protection in place. Mill machinery had to be stopped before children were made to clean it.

Over the following few years, many other laws were passed to make minor improvements to working conditions in factories.

The Factory Act (1878) brought together all existing rules about factories and added new laws, including the following:

- Factories had to be kept clean and properly ventilated

- Accidents had to be reported and investigated

- Children under the age of ten could not be employed.

- Children aged between ten and fourteen could only work half days in textile factories.

- Women were to work no more than 56 hours per week.

- Lunch breaks of at least one and a half hours had to be given

- Work on Sundays were banned (except in some cases for Jewish employers and workers)

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYMines and Collieries Act, 1842

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYIn 1838, a terrible flooding disaster at a coal mine in South Yorkshire led to the deaths of twenty-six children who had been working underground at the Huskar Colliery.

News of the deaths shocked the nations and Queen Victoria ordered an inquest into what had happened.

The end result was a new set of legislation aimed at improving working conditions in mines.

In 1842 the Mines and Collieries Act was passed. The act stated that:

- No women were allowed to be employed to work underground.

- No child under ten was allowed to work underground.

- More inspections of conditions underground were needed.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYSocial conditions during the Industrial Revolution

Image source, ALAMY

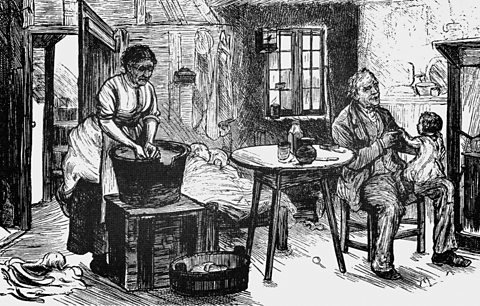

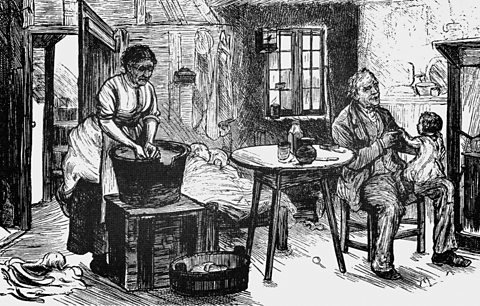

Image source, ALAMYThe huge growth of industry across the UK caused rapid urbanisationWhen somewhere becomes more urban. This means a greater percentage of people live in cities and towns rather than the countryside. as more people moved from rural areas to towns and cities.

With so many people pulled towards towns and cities for jobs, there were not enough places for them to live in.

It led to slum housingHouses that are of poor quality and tightly packed together. and poor living conditions. Families would often have to live in one or two rooms in high rise tenements as landlords crammed them in.

It was noted by a visitor to the Glasgow Wynds in 1844 that:

I did not believe, until I visited the wynds of Glasgow, that so large an amount of filth, crime, misery, and disease existed in one spot in any civilised countryâŠ.In the lower lodging houses, ten, twelve, or sometimes twenty persons of both sexes and ages would sleep on the floor

â

The overcrowding of large numbers of people in poor quality housing soon led to serious public health issues.

Poor sanitation, unsafe drinking water, and cramped conditions often led to infectious diseases spreading quickly.

It was the arrival of a devastating new disease, choleraA waterborne disease that was spread through contaminated water. It caused severe diarrhoea and sometimes death., that prompted the government of the day to find solutions.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe 1831 cholera outbreak

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYIn 1831, a new disease arrived in Britain and led to the deaths of thousands of people.

Cholera was a disease caused by the Vibrio cholerae bacteria. It was spread by people drinking contaminated water.

During 1830s, the disease spread across Europe, killing thousands of people.

It arrived in Sunderland, England, in 1831 and was soon found in other British cities.

It arrived in Scotland in 1832 and killed 3,000 people in Glasgow.

Across the whole of Scotland, around 10,000 people died. (J. Devine, The Scottish Nation, 2012).

Over the course of the next twenty years, several new outbreaks of the disease appeared - each time killing thousands.

Although, at the time, the cause of the disease was not known, it was generally assumed that poor sanitation and living conditions contributed to disease.

After another deadly cholera outbreak in 1848, the government passed new laws to improve public health.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYPublic Health Act, 1848

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYIn 1848, the government passed a Public Health Act that was designed to improve the health of the working class by improvements to housing, sanitation, and water quality.

The act stated that:

- A Central Board of Health should be established to oversee improvements.

- Local boroughs should be responsible for providing clean water supplies, adequate drainage, and streets clear of rubbish and sewage.

- Local Boards of Health must be established in areas where the death rate was above 23 per 1,000 people.

While the act did have flaws - many of its rulings were voluntary, and the Central Board of Health had few powers and no budget - it was an important first step in improving the lives of people who lived in towns and cities.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYGlasgow's new water supply

Image source, ALAMY

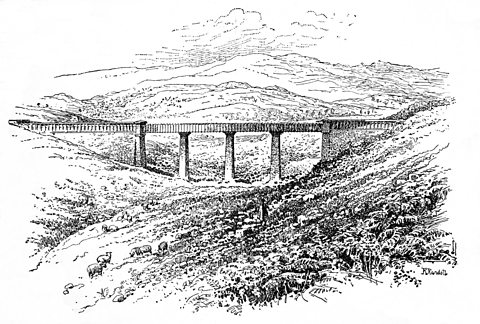

Image source, ALAMYAfter another outbreak of cholera in 1855, Glasgow took action to improve the city's sanitation and water supply.

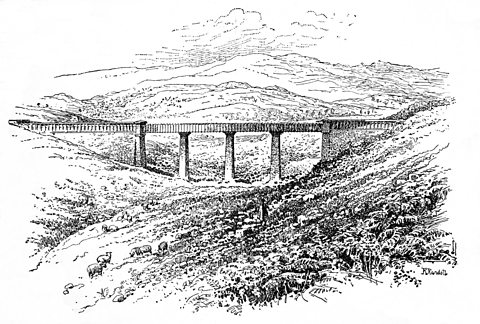

Loch Katrine in the Trossachs was dammed, and an aqueduct and tunnels built to transfer fresh water to the city. The scheme cost ÂŁ468,000, a huge amount at the time, and took four years to complete.

The money proved well spent and, together with improvements in the city's sewers, the fresh water supply helped eradicate cholera outbreaks in the city.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYPolitical reform during the Industrial Revolution

Image source, ALAMY

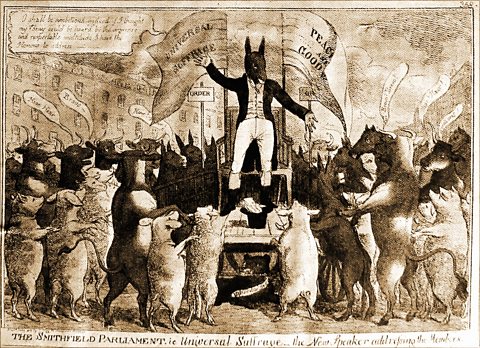

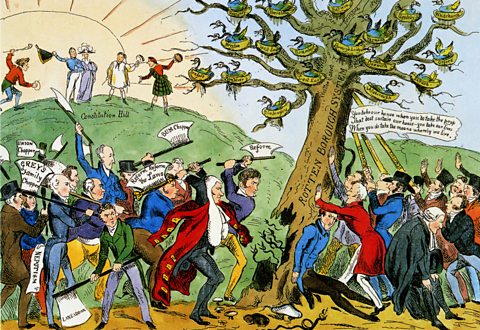

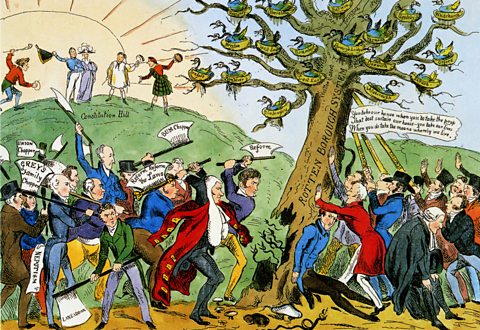

Image source, ALAMYBy the time of the Industrial Revolution, many people across Britain believed that the political system was unfair and excluded too many people.

Generally, the only people who could vote either owned land or had an income over a certain amount.

This ruled out the vast majority of working people and all women â voters were exclusively male. It even ruled out most of the educated middle classes.

The industrial revolution led to a bigger middle class â owners and managers of factories and businesses who had growing wealth, paid significant taxes and felt they should have more say in how the country was run.

A growing working class was aware that industry needed their labour. They lived and worked in poor conditions and wanted improvements, and they were becoming increasingly organised.

The system was also unbalanced in how many Members of Parliament (MPs) could be elected in different areas.

Some small ConstituencyThe people who live in a particular area and who can vote to elect a Member of Parliament to represent them. which small populations elected several MPs to represent them in parliament, while some big cities with large populations, such as Birmingham and Manchester, could not even elect one MP.

Protests

Image source, ALAMY

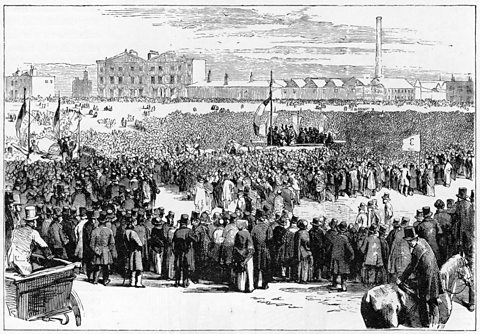

Image source, ALAMYDuring the early decades of the 1800s, pressure grew for political reform. Societies and institutions were formed that pushed for greater democratic participation. There were also organised marches and protests.

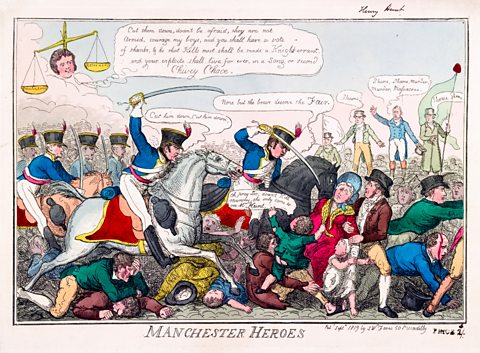

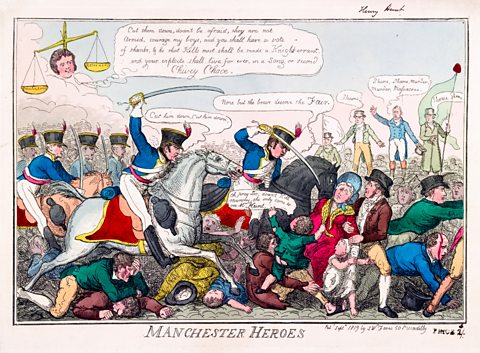

One of the best known happened at St. Peterâs Field, Manchester, in 1819. A mass crowd of around 60,000 people had assembled to listen to a speech by the radical speaker, Henry Hunt. An armed military force was dispatched the break up the meeting, and in the chaos that followed, 18 people were killed and over 700 were injured.

It became known as the Peterloo Massacre â a reference to the bloody battle at Waterloo that had happened four years earlier in 1815.

After years of campaigns, reform came in 1832.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYReform Act 1832

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYAfter years of trying to reform the political system, Parliament passed the Reform Act, 1832.

The act attempted to address some of the issues regarding who could vote and how many MPs each constituency could send to the House of Commons.

- It expanded the right to vote to small landowners, tenant farmers, shopkeepers, and households who paid over ÂŁ10 in yearly rent (the equivalent of around ÂŁ800 per year now).

- It abolished tiny electoral districts with few voters.

- It allowed larger towns and cities more MPs to represent them in the House of Commons.

The Reform Act (1832) gave the vote to many middle class men and skilled workers, but the working class was still excluded from voting in elections or becoming a Member of Parliament.

The working class was not satisfied and movements like Chartism campaigned for more change.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWho were the Chartists?

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe Chartist movement took its name from the publication of a document called the People's Charter of 1838.

The charter demanded political reform and greater political representation for the working-classes.

The movement had six aims:

- All men to have the vote.

- Parliamentary elections every year.

- Private ballots so each vote was secret.

- Members of Parliament (MPs) should be paid - that working-class people could afford to stand for election.

- No requirement for owning property to be an MP.

- Equal constituencies based on the number of voters in each area.

While the movement fizzled out in the 1850s, five of its aims were ultimately adopted with only the demand for annual elections refused.

Scottish Reform Act 1832

A separate act covered the political reforms in Scotland. They broadly addressed the same issues as the other Reform Act:

- Giving the vote to a wider section of the population.

- Giving towns and cities more MPs and better representation.

- The number of Scottish MPs in the House of Commons increased from 45 to 53.

While, like the other Reform Act, the Scottish Reform Act was limited it was an important first step to improve political representation.

As a result of the act, the number of people (males only at this stage) able to vote increased from around 5,000 to around 65,000. (Source: W. Ferguson, The Reform Act (Scotland) of 1832: Intention and Effect, 1966.)

Later reforms

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYLater reform acts would go further in extending the vote to more of the population.

- The Reform Act 1867 granted the vote to all householders and lodgers who paid a rent of more than ÂŁ10 a year, and to landowners and tenant farmers who owned small amounts of land.

- The Representation of the People Act 1884 allowed more people to vote by bringing voting rights in country areas into line with the ones in towns and cities.

- The Representation of the People Act 1918 gave the vote to all men over the age of 21 and to women over the age of 30.

- The Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 gave women the same voting rights as men. From 1928, women over the age of 21 had the right to vote.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYTest your knowledge

More on Industrial Revolution

Find out more by working through a topic