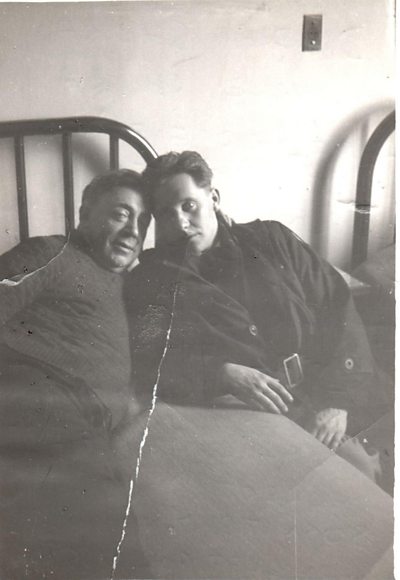

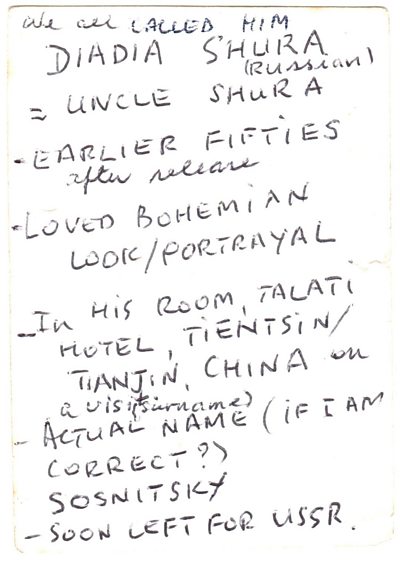

Peking Noir tells the life story of Shura Giraldi, a Russian émigré to China in the wake of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution. But the known facts of Shura's story were incomplete, which is where drama can fill in the gaps.

Historian and Dramatist explain how they worked together with producer Sasha Yevtushenko to create the Audio drama/documentary Peking Noir.

Paul:

Peking Noir is the life story of Shura Giraldi, a Russian émigré to China in the wake of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution. Shura was a minor character in my true crime book ‘’ who fascinated readers. However, there wasn’t really space to tell Shura’s whole life story in that book. , our producer at the Â鶹ԼÅÄ, was interested in Shura – both as a mercurial character and also as a symbol of the largely forgotten massive Russian exodus after 1917.

But Shura’s story also had so many gaps – perhaps a bank robber, a drug dealer, a nightclub entrepreneur and entertainer, lover of a government official and a Chinese warlord - so many issues that would be fun to dramatize. There were also aspects of Shura’s life that had fascinated many readers – that Shura sometimes presented as a man and sometimes as a woman depending on how that best suited Shura’s plans and moods – this felt quite contemporary.

Shura’s story, incomplete as it is, filled with gaps and suppositions, is still one of the best case studies we have of the life of an intersex person in the first half of the twentieth century. That’s both rare and interesting as well as quite important to recover. I had worked with Sasha and the dramatist on an earlier docu-drama retelling the story of the 2017 assassination of Kim Jong-nam at KL Airport, most probably at the behest of his half-brother, and the leader of North Korea, Kim Jong-un so I knew the format worked and Sasha suggested that I meet Sarah, who often works on dramatizing ‘real’ stories – Chappaquiddick, Rodgers & Hart and Hammerstein, Andy Warhol, the story of the National Theatre etc. It seemed an ideal pairing. Docu-drama works best where we simply can’t ever know all the facts, where there is always an element of informed guesswork that can help bring the story to life and convey real experiences.

Sarah:

I was asked to join the Peking Noir team by the producer Sasha in early 2020 and met Paul a few days before the first national lockdown. Before we met, I read all his books and at the first meeting we discussed the outline for the story and how the project might work over six episodes of fifteen minutes, all three of us throwing ideas around. After that, Paul went away and wrote a timeline of Shura’s life based on everything he had learnt from research – the facts (with records, pictures, memoirs where he had them) – and the rumours, gossip and suggestion. We had a google drive site and simply shared everything on there – Paul uploaded texts, pictures, a Spotify playlist in the hope that it would inspire myself and Sasha with characters, locations. When we had the first drafts of drama scenes, we could use those sources to ensure that though we were imagining scenes we were not distancing ourselves too far from history.

From that, I was able to start drawing up a detailed outline for each episode, making sure there were enough interesting twists and turns, plot progressions and exciting turning points etc. Sasha and Paul then gave me notes on the outlines and once we had that structure loosely in place I started to write each episode. Starting in a linear way (which is in fact Episode 2) and working forwards from there. There was a lot of scope for dramatic invention but we also had enough facts to give the whole thing a good clear shape.

Where possible we tried to incorporate ideas and developments into the dramatic script to 'up' the drama and reduce the documentary aspect to make things more exciting. I basically wrote the whole thing like an action film. As I went along I invented characters (always based on Paul’s research) – Marie for example is an amalgamation of two real people. Sasha then themed each episode. So Episode 2 was The Russian Exodus , Episode 3 was The Warlord and Shura coming to terms with being intersex etc so I knew what I needed to cover in each episode. We didn’t go back to Episode One till all the other episodes had been written and redrafted. Sasha would helpfully remind me that I didn’t have to sneak in any disguised exposition as Paul would be always be on hand to narrate to the listener, helping them leap from time zones and places with just one line. This allowed me to concentrate on the action. In terms of notes I’d deliver a draft of each episode and then get notes from Sasha and Paul and I’d re draft based on those notes.

Paul:

As the process went along we always tried to ensure that everything was historically justified. For instance we knew that Shura’s warlord lover had a lot of money and did buy property in Peking. I knew from my research that warlords in China were inveterate train robbers (think Marlene Dietrich and Anna May Wong in the movie ). I was able to show Sarah historical records of such train robberies, what sort of hauls the warlords got, what they spent their money on. She could then fire her imagination and dramatize a train robbery.

It is challenging however to bring this time and place to life. China, and Russia have a lot of history, even just the first fifty years of the 20th century and it’s not really taught in schools. As we say at the start of the show – ‘Set during two revolutions, and two world wars. It is a tale of bank robbers, jewel thieves, bordello madams, drug smugglers and...survival against the whirlwinds of history.’ That all needs some explaining, the drama needs to be placed in context as well as letting the audience know what we do know and what we are imagining so we intercut narration and drama with readings from memoirs, actual witness testimony and quotes from various well known characters of the time (including !).

Once I saw Sarah’s first dramatic scenes I could then write the narration around them so that the listener (hopefully) understands the context of the scene, the time and place and what we actually knew and what we surmised. Both the drama and the narration would change as we bounced the script between ourselves and Sasha. Eventually we found we could get a good balance and hopefully not repeat points made in the narration or in the drama and vice versa giving us scope to put as much into the two hours as possible.

Sarah:

Once we were all happy with the shape of the drama, Paul added his narration. There were times when it was more helpful and economical to drop a scene and have that be narration. Of course it’s all very well me writing bank robberies, shootings, and drug smuggling but someone has to make that world work for the listener and under lockdown conditions. We all agreed that we needed to cast an incredible group of actors and someone remarkable as Shura. Sasha and Paul had worked with , and before and a casting consultant very helpfully put Sasha in touch with a number of possible actors who identified as non-binary for Shura, we chose the brilliant .

We ended up recording the whole thing remotely and then Â鶹ԼÅÄ technical producer, Peter Ringrose brought it all to life in the edit. This was a massive amount to do in normal circumstances let alone under lockdown.

Paul:

Now the project is finished I think for me the biggest lesson I learnt was to let myself go when working with a dramatist. As a content originator you feel a certain ownership of the story and perhaps a greater affinity and protectiveness over the characters (especially as in this case they were mostly real people). I think that’s natural. Conflicts between authors and adaptors are commonplace. But this was always a partial story, full of gaps. At first I was nervous about what Sarah would come back with but when I saw the first few scenes I realised that we were going to take the story to a height that would be impossible without a great dramatist. It was those scenes, and not the narration placing them in historical context, that would make Shura and the rest of the cast of characters come alive.

Once you get past the sense of proprietary about the story then it all becomes a little more fun. I’m aware that at times I might have had to say, ‘sorry, I don’t think we can do that…’ when we strayed from the historically justifiable, but it wasn’t often. It was fun to be able to say to an experienced dramatist ‘we need a bank heist, a drug deal, a shootout, a revolution, a war!’ and get one back on email the next day. I hope we get to do it again, I have a few more ideas...

Listen to Peking Noir now on Â鶹ԼÅÄ Sounds

Read the script for Peking Noir in our Script Library