Weather forecasting: past, present and future

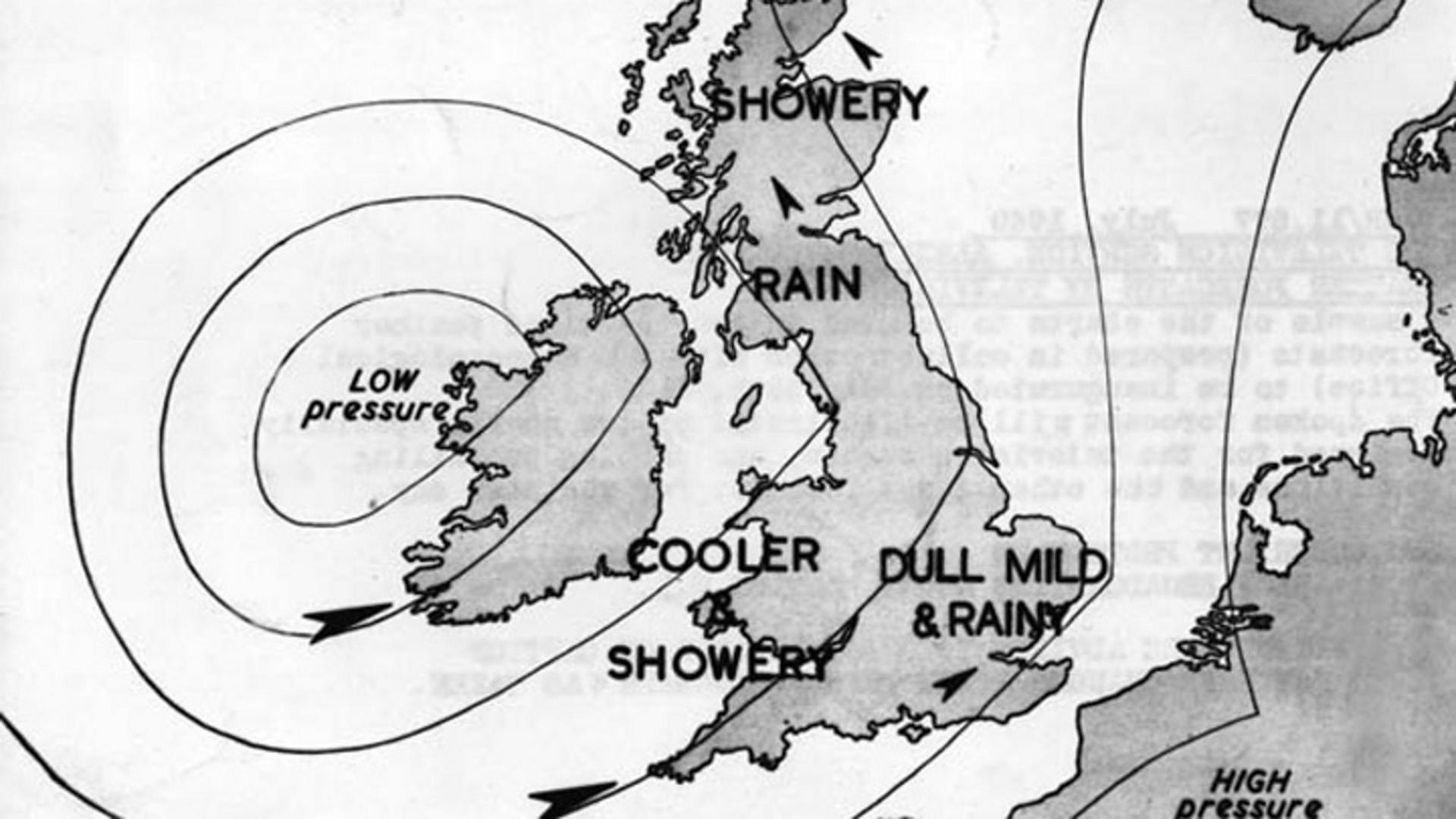

Low pressure brings rain to the UK in this weather map from 1949 - some things never change

- Published

It's 75 years since the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ's first regular television weather forecast hit the airwaves in July 1949.

It was basic by modern standards, consisting of a hand-drawn weather chart accompanied by a script written by the Met Office. These early TV forecasts were made in an age before computers revolutionised our ability to predict the weather.

The first Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ weather forecast would have been based on the ideas of Jacob Bjerknes who is credited with the discovery of weather fronts around the time of World War One.

A front is an area of active weather that forms along a zone between cold and warm air and was analogous to a wartime battlefront between two fighting forces.

By carefully analysing weather observations, a map could be plotted showing isobars (lines of equal pressure) as well as fronts - a skill still taught to trainee forecasters today. This map could then be used to forecast the likely weather and winds in the short term.

George Cowling became the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ's first in-vision presenter, five years later in 1954

Technological age

The tools that I take for granted today to help make accurate weather predictions were not available to previous generations of meteorologists.

The first photo from a weather satellite was taken on 1 April 1960, but it would be much longer before regular satellite imagery became widely available.

Colleagues who began their weather careers in the 1990s tell me that they would get just one poor quality infrared satellite image every six hours, delivered by a fax machine.

In contrast, today's weather satellites give us digital images every five minutes, in spectacular resolution and in a multitude of wavelengths. They can tell us not just about clouds, but the structure of moisture and winds through the entire depth of the atmosphere. They can detect wildfires, floods, volcanic ash and sandstorms.

Hurricane Florence, which struck the US east coast in September 2018, as viewed from the International Space Station

Weather radars are used to observe the extent and intensity of rain.

The UK weather radar network was commissioned in 1985 with four stations. Today, this has expanded to 15 stations and includes doppler technology that can be used to detect severe weather, including tornadoes.

But even today, the network doesn't cover the whole of the UK - Shetland remains off-grid.

A forecast model with 300m resolution was used during the sailing events at Weymouth during the 2012 Olympics

Supercomputers

Modern weather forecasts rely upon some of the very biggest computers on the planet.

The first Met Office operational computer forecast was produced on 2 November 1965 on a machine capable of 60,000 sums per second. In contrast, the current Met Office supercomputer, the Cray XC40, can calculate 14,000,000,000,000,000 (14 quadrillion) sums per second.

This is due to be replaced shortly by a Β£1.2bn supercomputer that will be even more powerful, capable of 60 quadrillion sums per second.

This vast increase in computing power has enabled higher resolution, longer range and more accurate forecasts.

When I started working at the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Weather Centre in 2001, the highest resolution model consisted of boxes 12km across. Fast-forward to today, and TV forecasts now regularly use a model with 1.5km resolution.

Weather conditions favourable for wildfires will become more common in a warming world

The future

Perhaps from reading this you get a sense that just like the weather, the technology that underpins modern forecasting is constantly changing and evolving. What about the future of weather forecasting?

Models using artificial intelligence are being created that could in the future provide new insights as to how our atmosphere works. They would run more quickly and wouldn't need the colossal number-crunching computing power used to make traditional forecasts.

Questions remain, however, as to whether AI models trained on past weather data will be able to make really accurate predictions as our planet's atmosphere continues to change and heat up.

These AI models are at an early stage of development, and on the occasions when I have looked at the forecasts they have produced, some have been good, and some have been bad. I have not seen any earth shattering differences to the traditional models yet.

However, the history of weather forecasting teaches us that whenever we have had step changes in technology, this has always lead to significant leaps in forecasting capabilities and in that sense, perhaps the future is easy to predict after all.

- Published29 July