The clocks go back on the night of Sunday 27th October - which means an extra hour in bed, but this may cause some confusion for young heads!

As every parent knows all too well, young children canât tell the time (this doesnât come until theyâre at primary school). But understanding the concept of time - including morning, afternoon and night; âbeforeâ and âafterâ and the changing seasons - comes much earlier. So you might get that lie in sooner than you thinkâŠ

Dr Jane Gilmour, Consultant Clinical Psychologist at Great Ormond Street Hospital, says, âWe seem primed to sense time and we share this ability with many other species â perhaps because itâs important for survival. Young babies can recognise the order of events by the time theyâre just one month old. More sophisticated time processing, like understanding past and present, takes longer to develop. This may be partly because the parts of the brain related to time processing develop at different rates as your child grows.â

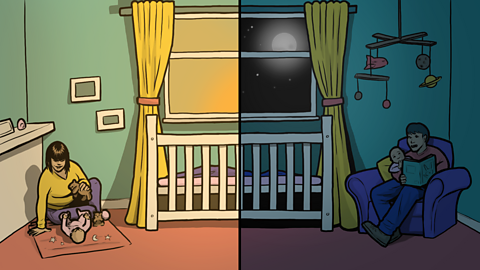

When do children understand night and day?

When your little one is constantly waking up in the early hours, it feels like theyâll never get to grips with night and day. But their body clock - also known as the circadian rhythm - actually develops early on.

Jane says, âThe sleep-wake cycle marks the beginning of recognising that night and day are two different periods. Hormones help our bodies develop a sleep-wake cycle and it takes time to fall into a rhythm. For most babies, their body clock will begin to settle from about 2 or 3 months old, but it may take longer for some babies. Babies are likely to be around 4 months old before they are in a steady sleeping schedule.â

Recognising that there are two different parts of the day will happen quicker if you use clear âsignalsâ to show itâs night or day, says Jane. âSignal the start of evening with a night time routine like a bath and a song that you only sing before bed. Keep noises low, lights out and avoid any exciting or stimulating interactions with your baby. Stay warm and loving, but be a bit âboringâ!â

When do children understand morning, afternoon and evening?

Babies are very good at predicting what comes next. âWe know babies can predict a sequence of events from as early as 4 weeks old (unconsciously at first)â, says Dr Gilmour. âIt means they can anticipate one thing comes after another. You only need to put a bib on your baby and theyâll predict that food is coming next.â

This skill means babies can also start telling the difference between different parts of the day. Give them a helping hand understanding morning, afternoon and evening by having a set routine at home.

If your morning and afternoon routines are specific for each portion of the day, babies will be able to learn the difference between them. Thatâs because they can recognise one regular event comes after another. Their sense of time is pretty well developed quite early on.

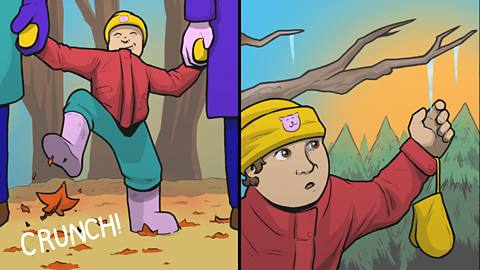

When do children understand seasons?

Your child will usually learn about seasons around preschool age. But you can help younger babies start understanding much earlier. Dr Gilmour says, âBabies learn by exploring the world using all their senses, so let them crinkle a brown leaf in autumn or touch ice in winter and talk about the changes in the seasons."

By offering them rich descriptions of what they can hear, see, smell or touch around them, you are helping them learn the seasons through play.

- Check out these fun autumn activities and weather play ideas

When do children understand âbeforeâ and âafterâ and past, present and future?

âFor the first few months of life, babies are living in the presentâ, says Dr Gilmour. âThough they can remember and learn from very early on in development, to some degree, the phrase âout of sight out of mindâ describes their approach to life.â

When your baby is around 8 or 9 months old they learn that something still exists in the world even if they canât see it. This is called âobject permanenceâ . A simple game of peekaboo is a great way to help them learn this.

But consciously knowing where they are in the past, present or future is a different story. âWhile children start to grasp these time concepts around the age of two, itâs an ongoing process that takes them well into middle childhoodâ, says Dr Gilmour.

To begin with, your childâs understanding of the past is better than their understanding of the future. Thatâs because the past relies on using their memories. The future is a lot more complicated!

The future means you âconstructâ a whole new idea, predicting events using knowledge about what has typically happened in the past.

Your childâs understanding of the future gets a boost when they are between 2 and 5. âDuring this time, toddlers get an idea that they will be present in the futureâ, says Dr Gilmour.

When children are around 4, they can describe the order of events in their day, and also across longer time periods. They can also order holidays or birthdays. But theyâll still find it hard to estimate periods of time in the future and might use vague terms like âsoonâ or âa long time from nowâ. Itâs not until the age of 7 or 8 that children can estimate time more specifically.

When can children tell the time?

Being able to tell the time is a skill your child develops as they get older. Dr Gilmour says, âChildren start to grasp the basics of telling the time in the early primary school years. Telling the time on a clock relies on a number of different skills. It needs spatial awareness and the ability to recognise and sequence numbers.â

Being able to estimate time periods is another big part of telling the time. But this can be tricky for young children. Dr Gilmour says, âEmotion has an impact on our estimate of time. We tend to overestimate time periods when we are looking at, or experiencing, something unpleasant. It means that science can explain why there are so many âare we there yet?â questions on boring journeys!â

According to Dr Gilmour, children donât fully understand the clock and calendar until theyâre around 10.

3 tips for teaching your child about time

1. Make it something they can see

Because time is a hard concept to grasp and very young children relate to âreal thingsâ better than concepts, try making time something they can actually see. Instead of saying, âIâll help you in 2 minutesâ, use a 2-minute egg timer so they can look at the sand as it runs through and understand how long there is to go before 2 minutes is up.

2. Try interactive routine charts

Help your toddler get to grips with the concept of âfutureâ with this They can see which âjobsâ they need to do and can tick them off when theyâre done. You can find all of our interactive charts here.

3. Play the âtomorrowâ game

Help your child by talking more about what is going to happen next. This âtomorrowâ game will help your little one learn about future tenses. Or try this simple activity âplanning adventures with teddyâ which helps your child think beyond the present.

Dr Jane Gilmour is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist at Great Ormond Street Hospital and co-author of How to Have Incredible Conversations with Your Child and The Incredible Teenage Brain.