The home front becomes the battlefront

'Blitz' is an abbreviation of the German word ÔÇśblitzkriegÔÇÖ, meaning ÔÇślightning warÔÇÖ. Its explosive sound describes the LuftwaffeÔÇÖs almost continual aerial bombardment of the British Isles from September 1940 to May 1941.

For eight terrifying months civilians across the country were in mortal danger. The Blitz made the home front the battlefront. It was not until the autumn of 1942 that the death toll of British soldiers exceeded the death toll of civilians.

3 September 1939

Before the Blitz

Minutes after Neville Chamberlain declares war on Germany a siren wails in London. People fear the much anticipated air attack on Britain has begun.

But it was a false alarm. As the Battle of the Atlantic against German U-boats raged furiously, and the Luftwaffe launched a number of daytime attacks, children were evacuated from cities and industrial centres. But HitlerÔÇÖs much feared concerted deadly air raids did not materialise. By the late spring of 1940 hardly anyone was carrying their gas mask and shelters were filling up with water through disuse.

The official government scheme to evacuate children started on 1 September 1939. Path├ę footage from June 1940 describes a 'great adventure'.

7 September 1940, 4.43pm

Black Saturday

Many people in the south-east of England are enjoying the Saturday afternoon sun when suddenly the sky darkens.

The drone of aircraft engines "like the far away thunder of a giant waterfall" made them scuttle indoors as wave after wave of bombers flew towards London. The siren known as ÔÇśWailing WinnieÔÇÖ or ÔÇśMoaning MinnieÔÇÖ because of its ululating notes sounded at 4.43pm. The white specks in the sky were making for the docks and soon the crump of bombs falling was interspersed with puffs of smoke as explosions set fire to riverside warehouses.

A Path├ę News report on 12 September 1940 depicts 'Murder From the Skies'.

7 September 1940, 6.30pm

Hundreds of rats

Hundreds of incendiaries (small candle-like bombs) fall on the docks. The fires are a beacon for a second wave of aircraft with high explosive bombs.

In a short time the docks were a mass of flames, molten sugar, burning liquor and hot tar. Hundreds of rats poured out of warehouses. Fire crews and Civil Defence workers arrived, but many were bogged down by the melted grain stuck to their boots like treacle. By 6.30pm the Dornier and Heinkel bombers, escorted by Messerschmidt fighter planes, had turned back towards France. The All Clear sounded. But this was just a lull.

7 September, 8.30pm

The Germans come back

The heavy bombers return. Soon an inferno stretches from London Bridge to Woolwich, a distance of around seven miles.

Water and gas pipes throughout the East End were fractured, as were electricity and telephone cables. More than 450 people were killed. The bombers would return to attack the capital for 57 consecutive nights until 7 November, when bad weather made it impossible for the Luftwaffe to fly. The primary target at this stage was not the civilian population but, given that employees lived near the docks and factories, the ÔÇścollateral damageÔÇÖ in terms of lives and homes was appalling.

Connie Hoe recalls her anxiety for loved ones in the East End of London. Britain's Greatest Generation (┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─ Two, 2015).

10 September 1940

Children

An advertisement in the Daily Herald encourages parents to "keep calm and cheerful" during air raids for the sake of their children.

Housewife magazine offered similar advice: "Air raids will only mean a great noise to younger children and provided Daddy and Mummy wonÔÇÖt mind they wonÔÇÖt." Air raid games were rife in the early months of the war, with children playing ÔÇśrescue partiesÔÇÖ in bomb sites that had once been their homes. Children who lost parents suffered terribly. Anna Freud, daughter of Sigmund, noted that one four-year-old girl in her nursery would not eat, speak or play and had to be moved around like an automaton.

┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─ recordings of a little boy describing a raid and of gas mask drill for primary school children.

13 September 1940

Underground

Frightened people swarm down the stairs at Holborn Underground Station. Officials make no attempt to keep them out, despite a government ruling.

Official policy had been to prevent Londoners sheltering in Tube stations, one of the reasons being that people and goods needed to be kept moving during the Blitz. But on the first night of bombing East Enders bought tickets for short journeys and defiantly refused to come up again. Thousands camped in cold, crowded and fetid conditions. By mid-September it was obvious to the authorities that to enforce a ban on sheltering in the Tube would risk ugly confrontations and a collapse in morale.

Robert Hall reports on how Londoners sheltered underground (┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─ London News, 2010).

October 1940

Fear and sexual desire

A doctor writing under the name ÔÇśA PsychiatristÔÇÖ notes in the Daily Herald: "I have met many conscientious citizens who are afraid of being afraid."

It was entirely rational to be afraid during the Blitz. But there was little medical help for people suffering mental anguish. A Dr George Franklin noted unusual behaviour caused by heighted anxiety: "Apparently normal people drank more alcohol. Sexual desire, especially in women, was much intensified. A number of men complained to me of their wives making excessive demands." Other doctors noticed an increase in peptic ulcers and advertisements for diarrhoea remedies increased.

14 October 1940

Balham

A bomb falls on Balham High Road above the intersection of Tube tunnels, killing 68 people sheltering in the station, including the stationmaster.

Many of the Balham victims were drowned by sludge and sewage from fractured pipes. It was now clear that nowhere was safe from a direct hit. Most people sheltered in corrugated iron Anderson shelters in their back gardens, brick-built public shelters or designated air raid shelters ÔÇô usually the basement of an office block or public building. Bridges, railway arches and cellars were also sought out, and an estimated 15,000 Londoners colonised Chislehurst caves in Kent each night.

15 October 1940

┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─

Listeners to a ┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─ news bulletin hear a crash as a bomb falls on Broadcasting House. Presenter Bruce Belfrage merely pauses before carrying on.

The nightly ┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─ news bulletin at nine oÔÇÖclock was a fixed feature in peopleÔÇÖs lives. Programmes went off air during raids, and the eerie fading of the radio was an early sign of an impending attack. While the ┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─ was trusted, it often came in for criticism. If the Ministry of Information asked it to describe a heavy raid as light, it would be accused of belittling victimsÔÇÖ suffering. If it reported a rural raid it would be accused of needlessly scaring parents whose children had been evacuated.

Image of Bruce Belfrage, accompanying audio clip contains a ┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─ reporter's account of fires raging in London.

14 November 1940

To Coventrate

Coventry, the centre of much of BritainÔÇÖs war production industry, is attacked in an overnight raid lasting almost 12 hours.

Although London attracted the bombers like a magnet, the Luftwaffe spread its net wide across the country. A new term ÔÇśto CoventrateÔÇÖ, meaning to ÔÇśdevastate by heavy bombingÔÇÖ, entered the language after Coventry was attacked by the light of a full moon. Factories, roads and railways were destroyed and 568 people were killed. This was an unprecedented number in one night. The dead had to be buried in mass civic funerals, with coffins laid two deep in long trenches.

Churchill inspects damage in Coventry. In a related video clip Eileen Bees recalls the raid for Blitz: The Bombing of Coventry (┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─ Two, 2010).

29 December 1940

The City of London

Amazingly, there were no raids on Christmas or Boxing Day 1940, but on 29 December the Luftwaffe returned. Their target was the City of London.

Soon after 6pm the mournful wail of the siren sounded. Over 300 incendiaries dropped in a minute around St PaulÔÇÖs Cathedral, "like apples falling from a tree". It was a perfect storm. The Thames was at a low ebb so firemen couldnÔÇÖt cross the mud to attach hoses to pumps. Burning wooden structures collapsed, blocking narrow streets. As it was a Sunday night, most city offices were locked and firemen couldnÔÇÖt gain access. Miraculously St PaulÔÇÖs Cathedral, symbol of LondonÔÇÖs defiance, survived.

Auxiliary fireman George Wheeler recalls his part in saving St Paul's Cathedral. The Week We Went to War (┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─ One, 2009).

January to May 1941

No port is safe

As the bitter winter drags on few places escape attack. The main targets are ports, ship yards and naval bases.

Merseyside received the unwanted accolade of being the second most heavily bombed place in the country. Hull, Swansea, Southampton, Portsmouth, Belfast, Bristol and Avonmouth also suffered. Clydeside, which had hoped it was out of range, was bombed in March. Not a single pub was said to be left standing. Over 4,000 homes were destroyed or damaged beyond repair in an already desperately poor area.

Residents recall their terror for Clydebank Blitz (┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─ One, 2011).

8 March 1941

Looting

LondonÔÇÖs Caf├ę de Paris is bombed. Looters work through the debris, easing rings from fingers, unclasping necklaces, rifling handbags for compacts.

Looting was the largely unspoken, unacknowledged underside of the ÔÇśBlitz spiritÔÇÖ. Some looters were bomb chasers. During a raid they would converge on the target area and smash shop windows as the bombs fell. The thievesÔÇÖ network would also pass on information about damaged houses where rich pickings might be had. Trinkets, underwear and food was stolen from smoking ruins and traumatised people. In 1941 there were 2,763 prosecutions for looting, 163 of the accused were women.

20 March 1941

Plymouth

The King and Queen visit Plymouth, which had been raided 13 times. Soon after they leave, the bombers come back to wreak havoc for three nights.

The "butcherÔÇÖs bill" as Churchill called it was almost certainly higher than the 1,172 claimed. Many bodies were never recovered. At the height of the raids there was almost a mutiny on HMS Jackal. Sailors refused to return to their stations unless they were promised shore leave to check on their families. Anyone who could trekked out of the city to the surrounding Devon countryside. They were dubbed "the yellow convoy" by a judgmental press.

April and May 1941

The cruelest months

Hull, Liverpool and Bootle are subjected to more heavy raids. Then on 10 May the sirens in London wail out soon after 11pm.

By the time the All Clear sounded just before six the next morning, a black pall of smoke hung over the capital. "After no other raid has London looked so wounded", wrote ChurchillÔÇÖs confidante Jock Colville. At 9.30 the next night the siren wailed again. "WeÔÇÖve had it", said one fireman to another. But an hour and a half later came the All Clear. There would be other serious raids over the next four years. But as Hitler prepared to turn east to invade Russia, the Blitz on Britain was over.

Despite a pact between the two countries, Germany invaded Russia on 22 June 1941. Charles Wheeler sets the scene in The Road to War (┬ÚÂ╣ď╝┼─ Two, 1989).

Learn more about this topic:

WW2: Could you be part of a Lancaster Bomber crew? document

A Lancaster bomber was one of the most dangerous places to be in WW2. Find out if you would have what it takes to be part of the crew.

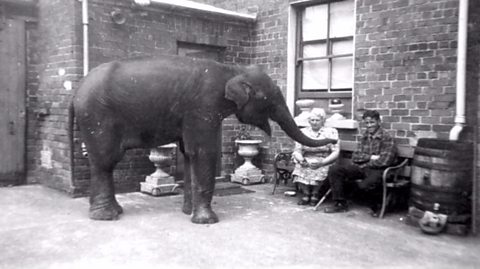

WW2: How did an elephant beat the Belfast Blitz? document

Elephant in the garden: How extreme measures were taken to keep people, properties and animals safe during the Belfast Blitz.

WW2: What would you have done when the bombs fell? document

The Blitz of WW2, sometimes known as the London Blitz, was the German bombing campaign that lasted eight months and targeted 16 British cities.